Can you imagine a world without the music of Handel, Tchaikovsky, or Britten? These great composers of the past are just a few of many important musical figures who did not identify as heterosexual. Check out this list of 15 composers, from the 17th century to today!

Can you imagine a world without the music of Handel, Tchaikovsky, or Britten? These great composers of the past are just a few of many important musical figures who did not identify as heterosexual. Check out this list of 15 composers, from the 17th century to today!

Jean-Baptiste de Lully

Jean-Baptiste de Lully

(November 28, 1632 – March 22, 1687)

After dancing with King Louis XIV in 1653’s Ballet royal de la nuit, Lully was engaged as the court’s royal composer, essentially granting him a monopoly over new music and kickstarting what would be a charmed career. However, Lully’s lack of discretion contributed to his downfall: the King could not turn a blind eye to Lully’s brazen liaisons with both men and women. Lully’s affair with a handsome music page named Brunet eventually leaked to the general public, who literally sang about it in the streets of Paris. By the time Lully died, he’d fallen from the King’s favor.

Listen to “Enfin, il est en ma puissance” from Lully’s Armide (Les Arts Florissants dir. William Christie).

Georg Friedrich Handel

Georg Friedrich Handel

(February 23, 1685 – April 14, 1759)

An intensely private man, Handel never married. He once dismissed King George II’s inquiries about his love life by insisting that he had no time for anything but music. However, what is undeniable is that Handel socialized in circles in which homosexuality was an open secret, from the Italian and German courts to his artistic cadres in London. Handel expert Dr. Ellen Harris wrote about his private life in Handel as Orpheus: Voice and Desire in the Chamber Cantatas, which explores themes of sexuality in his works and remains the authoritative book on the subject.

Listen to “Come rosa in su la spina” from Handel’s Apollo e Dafne (HWV 122) (Russell Braun, Les violons du Roy, dir. Bernard Labadie).

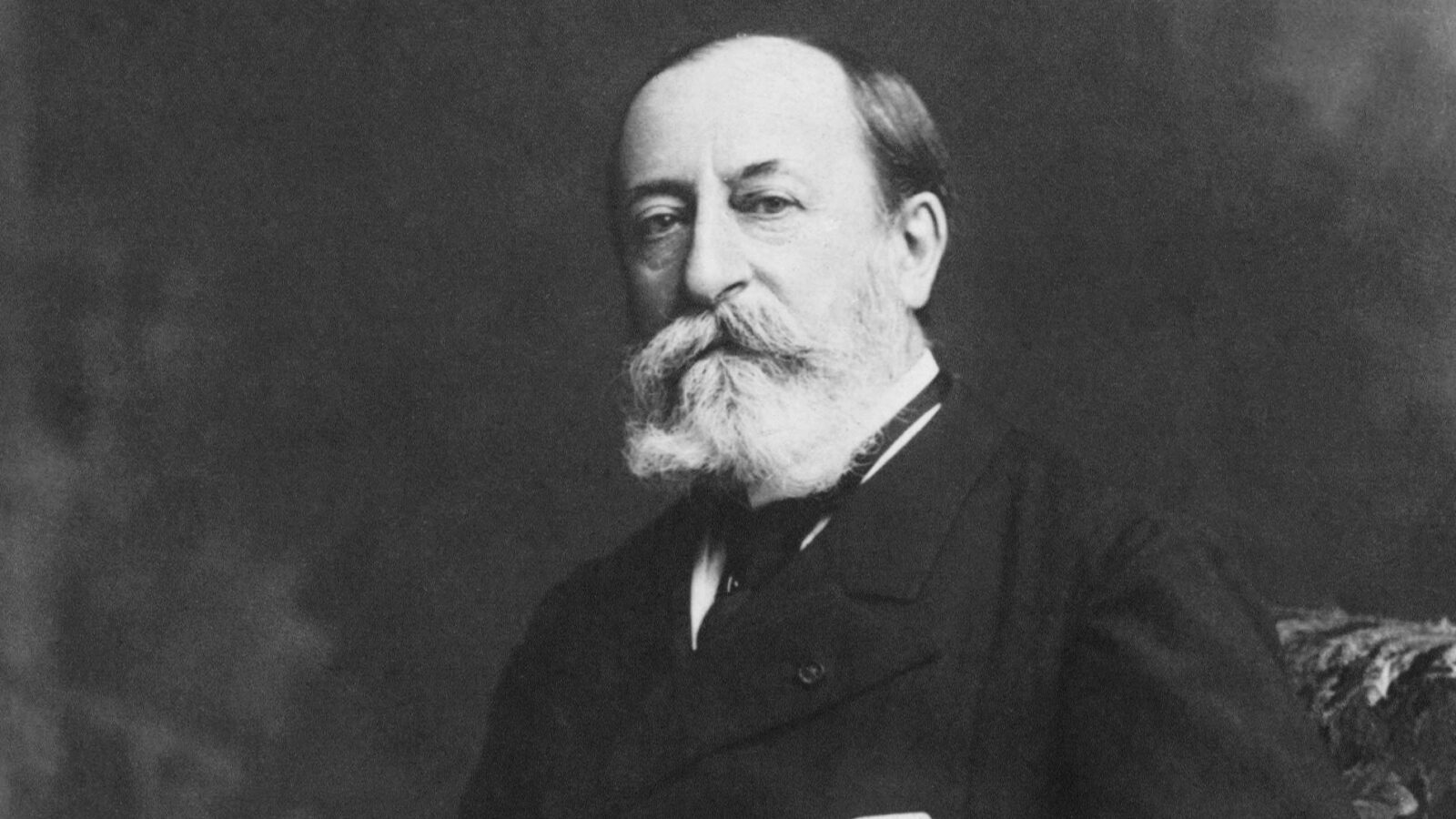

Camille Saint-Saëns

Camille Saint-Saëns

(October 9, 1835 – December 16, 1921)

In 1875, the 40-year-old Saint-Saëns surprised friends and family when he hastily married Marie-Laure Truffot, the sister of one of his pupils. The marriage was an unhappy one: after the deaths of their two young children, Saint-Saëns walked out on Truffot and never remarried. Despite this painful chapter in his life, he remained social and outgoing, hosting lavish soirees—where he supposedly performed in drag on more than one occasion—and indulging in frequent travel to exotic locales in Northern Africa. Some have speculated that he might have pursued trysts in Algiers, then a popular destination for European homosexuals.

Listen to Saint-Saëns’ Piano Concerto No. 5, Egyptian (Jean-Yves Thibaudet with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, dir. Andris Nelsons).

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

(May 7, 1840 – November 6, 1893)

Though the composer wrote about his sexuality at length in his letters to his brother Modest (also gay), Tchaikovsky’s immense fame and fear of flouting social convention precluded him from living openly with a male partner. Not unlike Saint-Saëns, Tchaikovsky’s short-lived marriage to a younger woman, Antonina Miliukova, was a catastrophe. Perhaps the closest Tchaikovsky came to publicly revealing his orientation was with his Symphony No. 6, the Pathétique. He dedicated the work to his lover Vladimir “Bob” Davydov (who also happened to be his nephew). Despite myriad primary accounts that discuss Tchaikovsky’s homosexuality, the Russian government’s long history of anti-gay censorship has muddied the biographical waters in Tchaikovsky’s beloved homeland.

Listen to Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6, Pathetique. (Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, dir. Georg Solti).

Ethel Smyth

Ethel Smyth

(April 23, 1858 – May 8, 1944)

As to be expected from a pioneering female composer and suffragette, Smyth displayed a keen musicality and sense of social justice from a young age. At only 12, Smyth announced her intention to study at the Leipzig Conservatory, which she later attended. She had a number of infatuations with women throughout her life, including an unrequited love for Virginia Woolf. She once wrote to her friend, librettist Henry Bennet Brewster, “I wonder why it is so much easier for me to love my own sex passionately than yours. I can’t make it out for I am a very healthy-minded person.”

Listen to Smyth’s overture to The Wreckers (Scottish National Orchestra, dir. Sir Alexander Gibson).

Francis Poulenc

Francis Poulenc

(January 7, 1899 – January 30, 1963)

The composer of a vast catalog of religious music, Poulenc once wrote to a friend, “You know that I am as sincere in my faith, without any messianic screamings, as I am in my Parisian sexuality.” Indeed, Poulenc was a lifelong Roman Catholic whose most lasting romantic relationships were with men. Though he fathered a daughter, Poulenc left behind more information about his gay relationships than his heteronormative ones. A copy of his Concert champêtre bears the following inscription to his then-partner Richard Chanlaire: “You have changed my life, you are the sunshine of my thirty years, a reason for living and for working.”

Listen to Poulenc’s Concert champêtre (Wanda Landowska with the Philharmonic Symphonic Orchestra, dir. Leopold Stokowski).

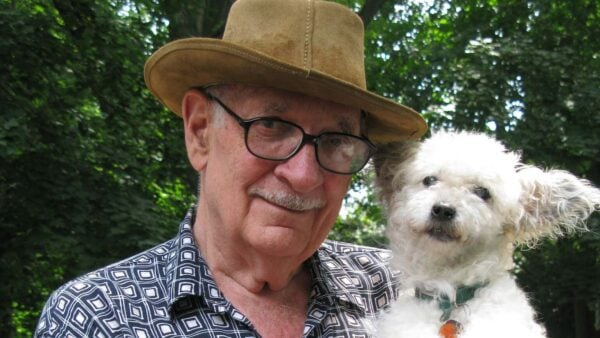

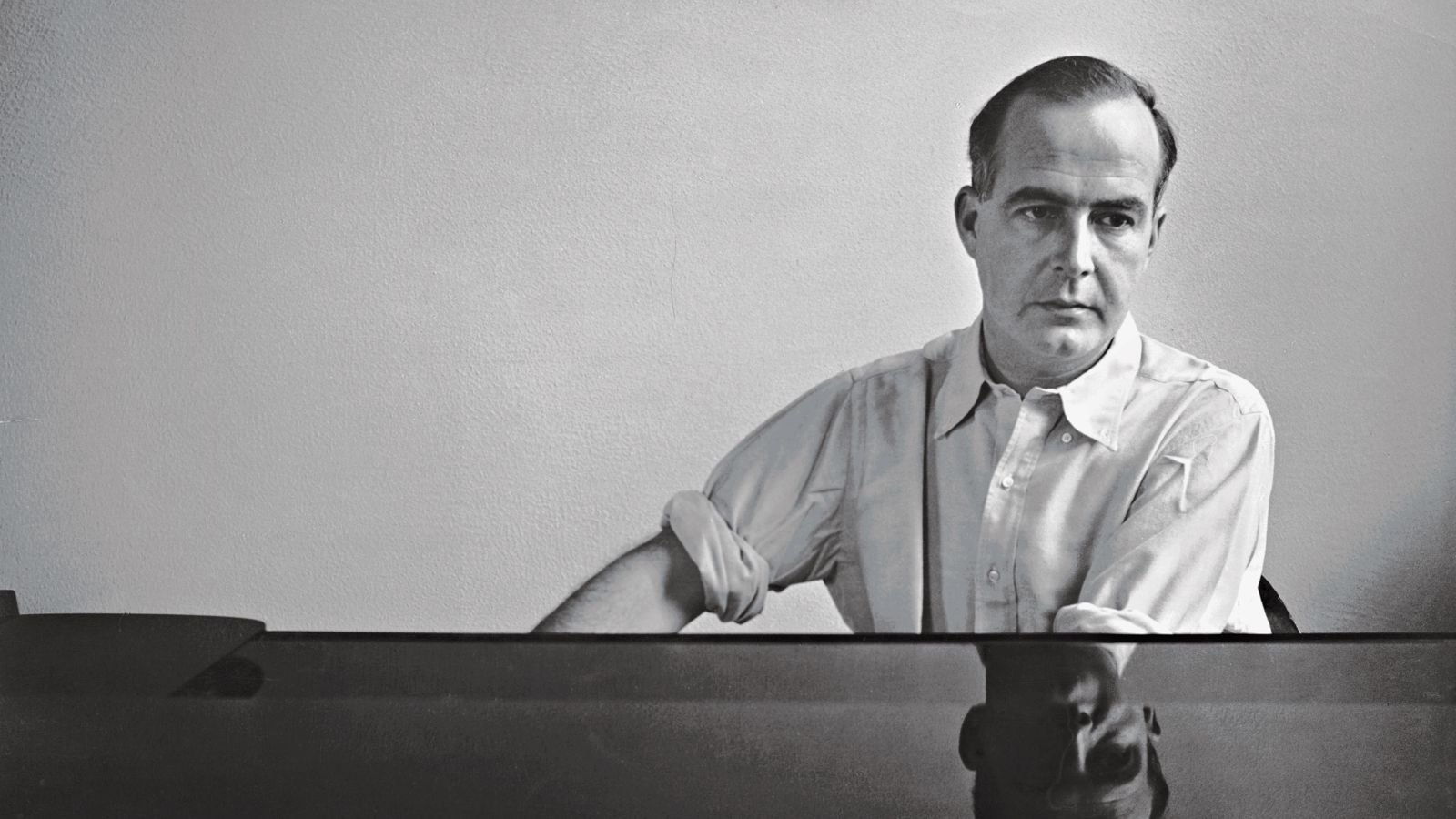

Aaron Copland appeared on “John Callaway Interviews” on WTTW on September 14, 1981.

Aaron Copland

(November 14, 1900 – December 2, 1990)

Though never outspoken on the subject, Copland felt little to no angst about his sexuality. He never went to great lengths to hide his relationships, most of which were with talented young men who ran in his cultural sphere. Nor did his homosexuality interfere with his success as a composer, though it may have contributed to his blacklisting during the Red Scare. At one point, Leonard Bernstein pressured his mentor and friend to publicly come out. Copland wryly responded, “I think I’ll leave that to you, boy.”

Listen to Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man (San Francisco Symphony, dir. Michael Tilson Thomas).

Samuel Barber

Samuel Barber

(March 9, 1910 – January 23, 1981)

Barber met fellow composer Gian Carlo Menotti when they were both students at the Curtis Institute of Music. It was the beginning of a long and fruitful partnership: Menotti provided libretti for Barber’s operas Vanessa and A Hand of Bridge, and between them, the men would win four Pulitzer Prizes. They would be together for nearly thirty years in a house they called Capricorn (also the name of Barber’s concerto for oboe, trumpet, flute, and strings). Later in life, the men’s relationship dissolved, contributing to Barber’s eventual creative drought and depression.

Listen to Barber’s Capricorn Concerto (Joseph Mariano, Sidney Mear, and Robert Sprenkle with the Eastman-Rochester Orchestra, dir. Howard Hanson).

Benjamin Britten & Peter Pears

Benjamin Britten

(November 22, 1913 – December 4, 1976)

Britten was introduced to tenor Peter Pears through a mutual friend. When that friend died in a plane crash in 1937, both men volunteered to help move his possessions. That project would be the first of many between the two, marking the beginning of a professional and personal relationship that would last more than 40 years. Britten would compose several opera roles and song cycles for Pears, who in turn became the foremost interpreter and champion of Britten’s vocal music. Of their relationship, Pears’ niece, Sue Phipps, said: “They made a conscious decision to neither flout it nor ignore it.”

Listen to Britten and Pears perform and discuss excerpts from Winterreise, from 1968.

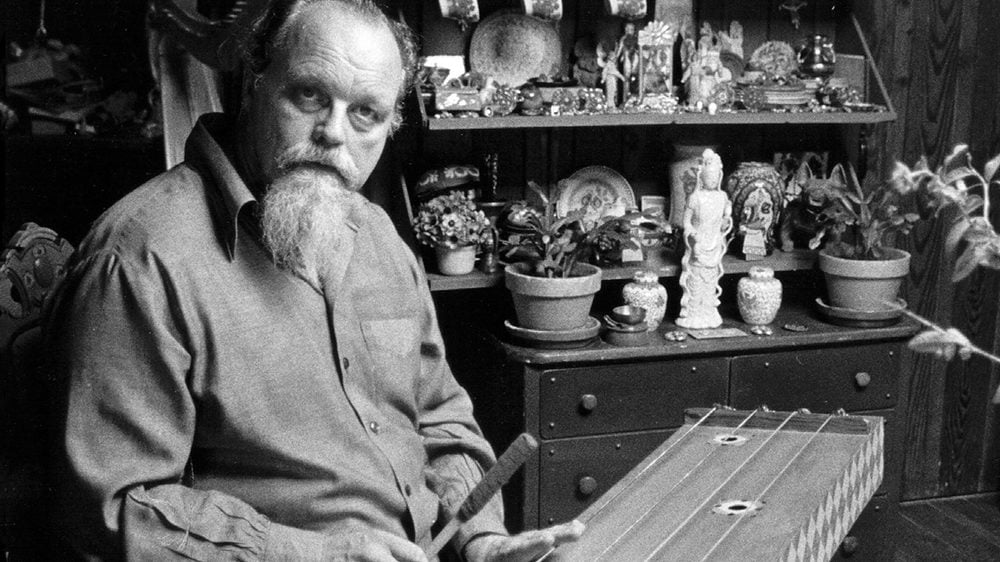

Lou Harrison

(May 14, 1917 – February 2, 2003)

Not only was Harrison gay, but he was also an outspoken gay rights activist. His strong sense of identity manifested itself in arrangements and commissions for several American gay men’s choruses, and he was recognized for his achievements by the Annual Gay/Lesbian American Music Awards in 1999. As AIDS researcher and co-founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis Lawrence Mass noted, Harrison was “proud to be a gay composer and interested in talking about what that might mean.”

Listen to Harrison’s Strict Songs, No. 1: Here is Holiness, arranged for eight baritones and orchestra. (Louisville Orchestra, dir. Robert Whitney).

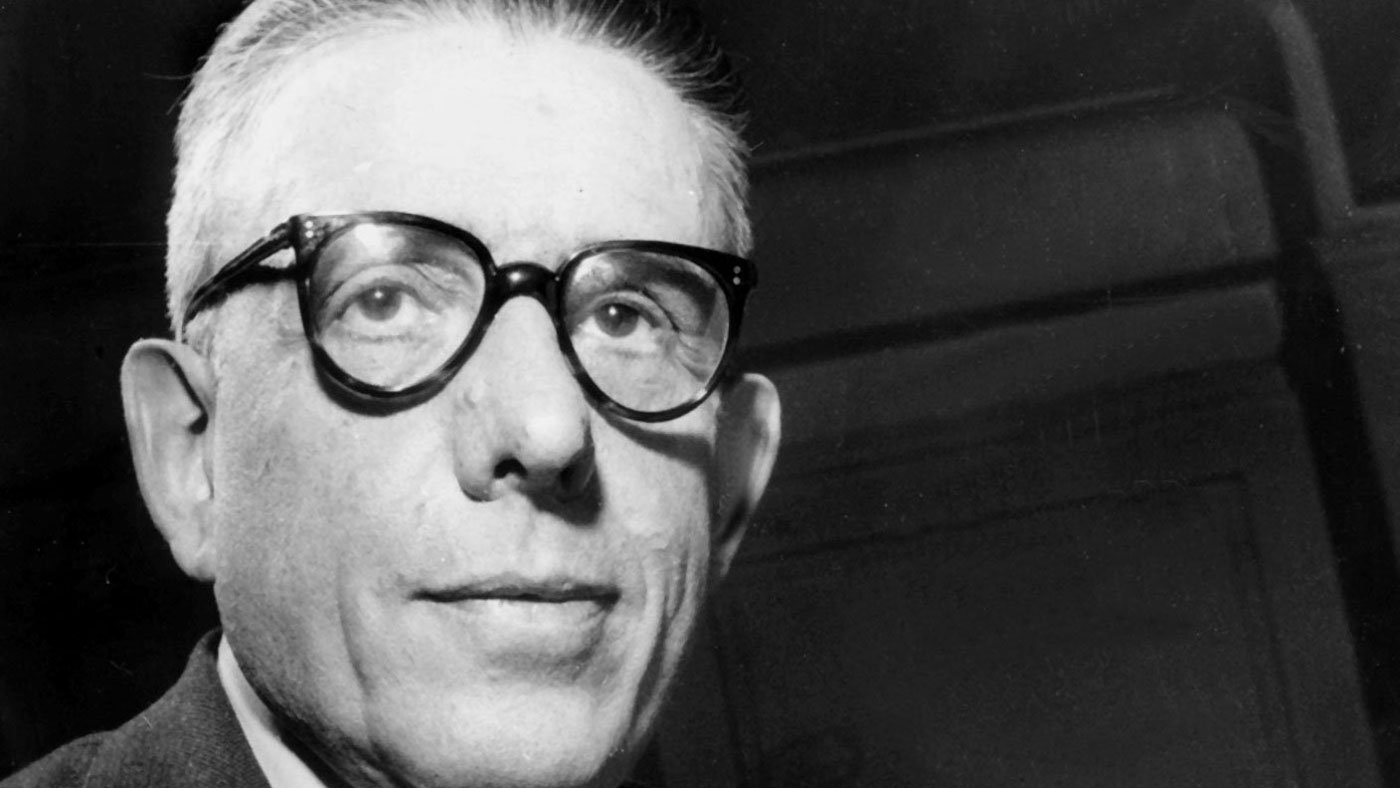

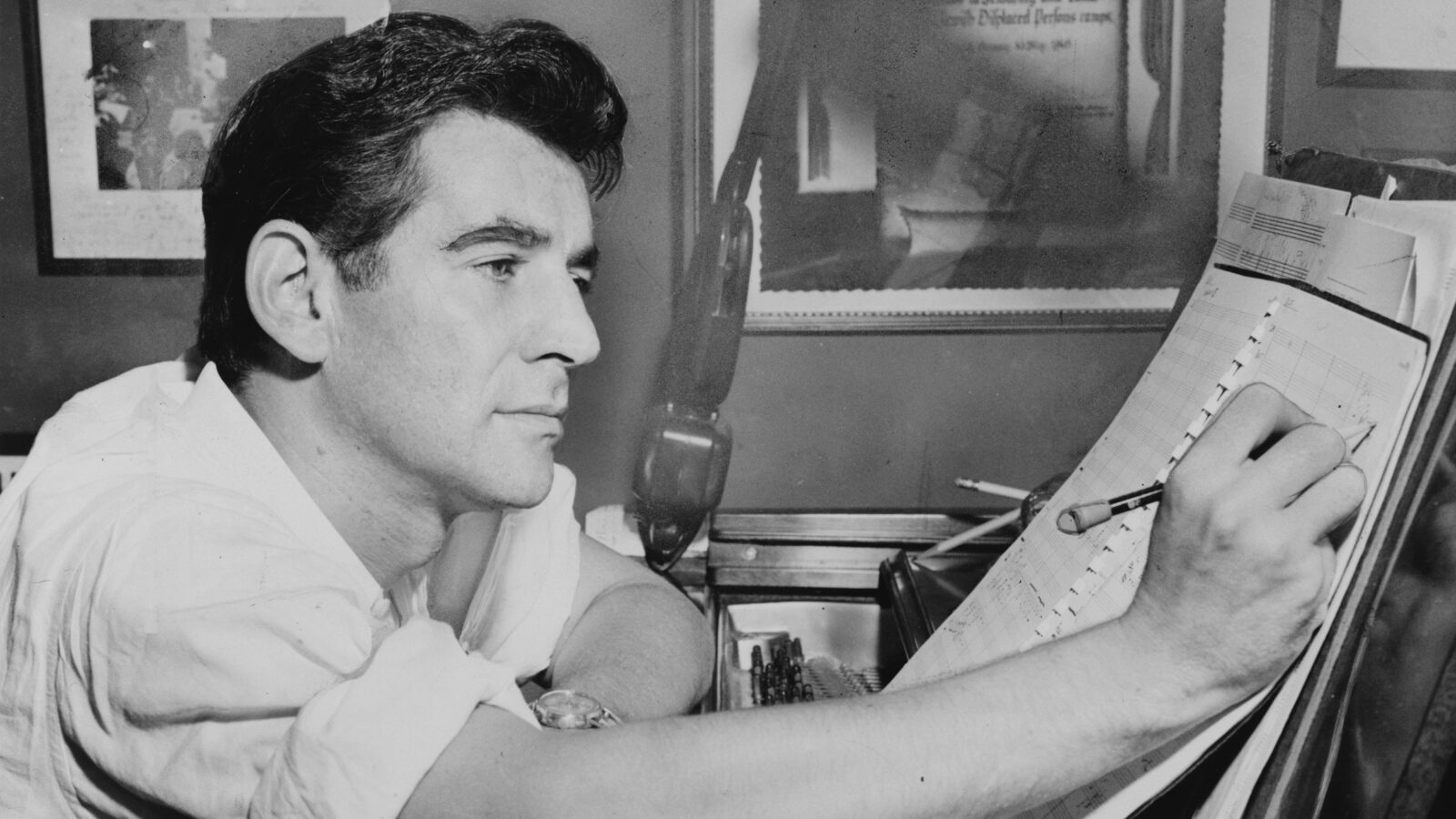

Leonard Bernstein

(August 25, 1918 – October 14, 1990)

Something of a wunderkind, Bernstein rubbed elbows with the American classical elite before he’d even graduated college. Knowing that conservative orchestra boards would not tolerate having an openly gay music director, Bernstein married actress Felicia Montealegre in 1951. Though he adored his wife and children—and was devastated by Felicia’s death in 1978—he carried on a string of affairs with men that only became less discreet as he grew older. Arthur Laurents, Bernstein’s collaborator during West Side Story, put it simply: “He was a gay man who got married. He wasn’t conflicted about it at all. He was just gay.”

Listen to an excerpt from Bernstein’s A Quiet Place (Louise Edeiken, Mark Thomsen, and Kurt Ollmann with the Vienna Radio Symphony, dir. Leonard Bernstein).

Pauline Oliveros performs in 2012 (Photo: Pinar Temiz, CC-BY-SA 2.0)

Pauline Oliveros

(May 30, 1932 – 2016 )

Alongside composers like Terry Riley and Loren Rush, Oliveros has been long-established as a member of the American musical avant-garde. She coined the concept of “Deep Listening,” which incorporates meditative practices like self-awareness with performance to “cultivate a heightened awareness of the sonic environment.” Unconventionally, Oliveros’s first instrument was the accordion, and she continues to perform on the instrument internationally. In 1971, she came out in her music journal Sonic Meditations in Source. She is an outspoken feminist who has collaborated with all-women ensembles, as well as other queer artists.

Listen to Oliveros’s To Valerie Solanas and Marilyn Monroe in Recognition of their Desperation. (Hope College. 1970).

Wendy Carlos

(November 14, 1939 – )

Carlos was the architect behind an innovative endeavor: the electronization of Baroque master J.S. Bach’s most famous music. Upon its 1968 release, Switched-On Bach became one of the classical world’s greatest runaway hits, helping to legitimize electronic and synthesized music as serious genres. She has composed music for iconic films such as A Clockwork Orange and The Shining.

Listen to Carlos’s “Main Title” from The Shining.

Photo: Candice DiCarlo

Jennifer Higdon

(December 31, 1962 – )

A professor at the Curtis Institute of Music, Higdon is recognized as one of the classical world’s most celebrated contemporary composers. She won the 2010 Pulitzer Prize in Music for her Violin Concerto and a 2009 Grammy Award for her Percussion Concerto. Her first opera, Cold Mountain, receives its world premiere at the Santa Fe Opera in August 2015. She married longtime partner Cheryl Lawson in August 2014, whom she met in band class in high school. Conductor Marin Alsop officiated their wedding.

Listen to Higdon’s Percussion Concerto (Jeffrey Lawi with the University of British Columbia Symphony Orchestra, dir. Raffi Armenian).

Nico Muhly

Nico Muhly

(August 26, 1981 — )

Muhly is a genre-bending composer whose most recent opera, Sentences, centers on the life of Alan Turing, the famed Enigma code cracker who was also gay. But Muhly has underplayed whatever personal connection listeners might draw between his experience as a gay composer in the twenty-first century and Turing’s. “I don’t want to be like [in a mocking, high-pitched voice]: ‘I responded to his story in a very personal way,’” he told the Guardian earlier this month. “No one wants a gay martyr oratorio.” His opera Two Boys also deals with gay relationships.

Watch the Metropolitan Opera’s video preview of Muhly’s Two Boys from its 2013-14 season.

Who are some other LGBTQ composers and musicians that you love? Tell us in the comments below!