The Národní Muzeum, or National Museum in Prague. (Photo: Che, CC BY-SA 2.5)

Franz Joseph Haydn’s Cello Concerto No. 1 collected dust for nearly 200 years in the National Museum in Prague before it became a staple of the cello repertoire.

Music historians had always known of the concerto’s existence, thanks to Haydn’s diligent records: the work is included in both of his personal catalogues, dating it circa 1765. Beyond those brief mentions, practically nothing was known about the concerto, including its whereabouts, and for years it was assumed lost.

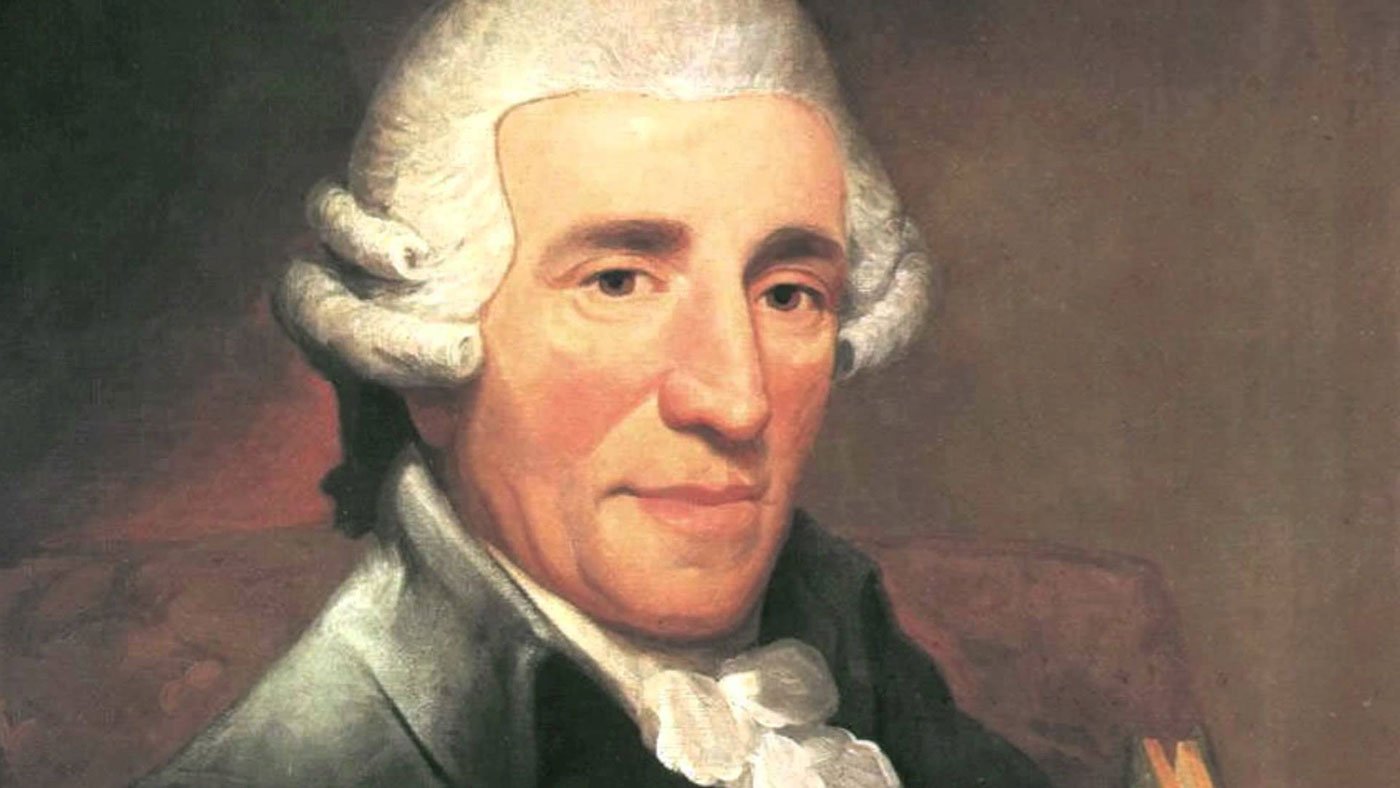

Franz Joseph Haydn

That all changed in 1961. One day, Oldřich Pulkert, an archivist of the National Museum in Prague, was digging through old documents collected from a chateau in Radenín, a tiny village in southern Bohemia. Within the papers, Pulkert found a set of orchestral parts signed by Joseph Weigl, the principal cellist in the Esterházy court orchestra from 1761 to 1768.

Upon discovering the work, several pieces fell into place. The theme of the concerto matched the one jotted down in Haydn’s personal catalogues, and a motif even appears in the first movement which quotes “Destatevi O miei fidi,” a celebratory cantata Haydn had composed for Prince Nikolaus Esterházy I’s name day in 1763, according to a liner note for a Naxos recording of Haydn Cello Concertos No. 1, 2, and 4.

Haydn wrote most of his concertos while he served as a court musician for the Esterházy family. The court orchestra was full of talented soloists who could display their skills in virtuosic concertos.

Among these musicians was Weigl, the cellist whose signature was on the rediscovered parts. He and Haydn began working for the Esterházys within months of one another. And only one cellist was thought to play in the orchestra during those years: Weigl.

Haydn Hall where the composer’s Cello Concerto No. 1 likely premiered, at Eszterházy Castle, Eisenstadt, Austria (Photo: Zairon, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The parts indicate that Weigl may have been the work’s dedicatee. Haydn was especially close to Weigl even before they entered the service of the Esterházy court. They became friends in Vienna and Haydn was godfather to two of Weigl’s children, according to The Faber Pocket Guide to Haydn.

The discovery caused a stir and H.C. Robbins Landon, a noted Haydn researcher, hailed the discovery as “the single greatest musicological discovery since the Second World War.”

Cellists were delighted to have a genuine companion to Haydn’s Cello Concerto in D, particularly since the composers’ Third Cello Concerto has been long lost—probably in one of a number of fires at the Esterházy estate in the intervening years—and the authenticity of a subsequent fourth and fifth has since been largely dismissed by researchers.

We still don’t have any details about the premiere performance of the Cello Concerto No. 1 during Hayden’s lifetime, nor do we know whether Weigl was indeed the cellist to perform it. As for the rediscovered piece’s modern premiere, that honor fell to Czech cellist Miloš Sádlo.

An obituary printed by The Guardian after his death in October 2003 described him as “the doyen of Czech cellists,” but his renown transcended borders: he was among Dmitri Shostakovich and Bohuslav Martinů’s favorite interpreters, premiering Martinů’s Cello Concerto No. 1 and Shostakovich’s Piano Trio No. 2, with David Oistrakh on violin and the composer on piano.

Sádlo gave the modern premiere of Haydn’s Cello Concerto No. 1 with the Czech Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Sir Charles Mackerras, on May 19, 1962. A recording (for the Czech label Supraphon) soon followed, and he worked with fellow cello great Mstislav Rostropovich to edit the concerto for the first cello and piano transcription by International Music, including composing cadenzas for performers who cannot improvise or compose their own.

Now, more than half-a-century after it has been discovered, Haydn’s Cello Concerto No. 1 has been performed and recorded by practically every great cellist of the 20th and 21st century. Researchers aren’t holding their breath for the rediscovery of Haydn’s Cello Concerto No. 3 anytime soon. But the story of the Cello Concerto in C will certainly make you appreciate the tireless efforts of archivists around the world.

Listen to Haydn’s Concerto No. 1, as performed by Mstislav Rostropovich and the Orquesta Sinfónica de Radiotelevisión Española, below.