Frédéric Chopin composed nocturnes throughout his career, including 18 published between 1832 and 1846 and 3 published posthumously. The first person to title instrumental works of this kind “nocturnes” was John Field. He published a collection of piano nocturnes in the early 19th century.

In a eulogistic preface to an 1859 edition of John Field’s collected nocturnes, composer Franz Liszt poetically described the emotions they evoked:

“The title Nocturne aptly applies to the pieces so named by Field, for it bears our thoughts at the outset toward those hours wherein the soul, released from all the cares of the day, is lost in self-contemplation, and soars toward the regions of a starlit heaven.”

Liszt goes on to a detailed comparison of Field’s nocturnes with Chopin’s, writing:

“Chopin, in his poetic Nocturnes, sang not only the harmonies which are the source of our most ineffable delights, but likewise the restless, agitating bewilderment to which they oft give rise. His flight is loftier, though his wing be more wounded; and his very suaveness grows heartrending, so thinly does it veil his despairful anguish… Their closer kinship of sorrow than those of Field renders them the more strongly marked; their poetry is more sombre and fascinating; they ravish us more, but are less reposeful; and thus permit us to return with pleasure to those pearly shells that open, far from the tempests and the immensities of Ocean, beside some murmuring spring shaded by the palms of a happy oasis which makes us forget even the existence of the desert.”

Chopin’s nocturnes may also have been influenced by another contemporary musical tradition – bel canto singing. There was plenty of opera to be heard in Warsaw while Chopin was at school, and his time in the cultural hothouse of Paris would only have cemented such an interest. In particular, the shapes of Chopin’s melodies often seem to bear a resemblance to the operatic arias of such Italian masters as Bellini and Rossini, with whose work Chopin was quite familiar.

Explore some of Chopin’s piano nocturnes below.

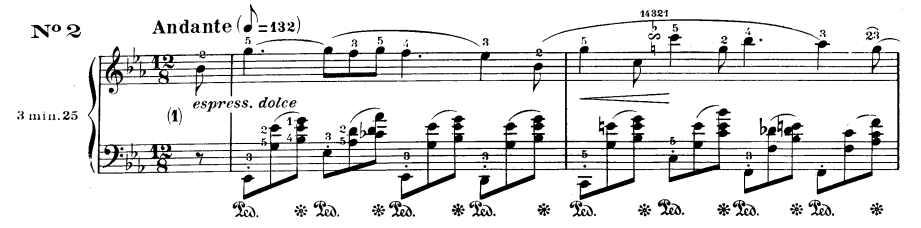

Nocturne Op. 9, No. 2 (E-Flat Major)

Chopin was 20 years old when he wrote Nocturne Op. 9, No. 2. It melody is reminiscent of arias Chopin may have heard at the opera, and it’s no surprise that other composers have arranged this piece for the human voice. Composer Sergei Rachmaninoff was particularly fond of this nocturne, and his recording of it can be found here.

Chopin was 20 years old when he wrote Nocturne Op. 9, No. 2. It melody is reminiscent of arias Chopin may have heard at the opera, and it’s no surprise that other composers have arranged this piece for the human voice. Composer Sergei Rachmaninoff was particularly fond of this nocturne, and his recording of it can be found here.

Nocturne Op. 9, No. 3 (B Major)

This nocturne is marked scherzando (joking), which is a bit unusual for a nocturne. Conductor and bel canto expert Will Crutchfield wrote about a possible connection between Rossini’s La gazza ladra and Op. 9 No. 3, saying:

This nocturne is marked scherzando (joking), which is a bit unusual for a nocturne. Conductor and bel canto expert Will Crutchfield wrote about a possible connection between Rossini’s La gazza ladra and Op. 9 No. 3, saying:

“The operatic score that meant most to Chopin was almost certainly La gazza ladra (The Thieving Magpie). Known today only for its brilliant overture, it was a repertory staple in Chopin’s time. The story tells of a peasant serving-girl wrongfully accused of stealing silverware that has in fact been filched by a magpie with a predilection for shiny ornamental objects.”

Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 (D-Flat Major)

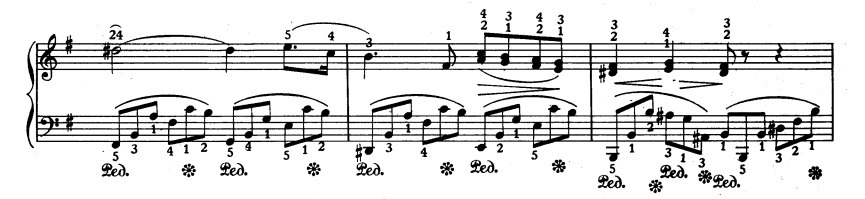

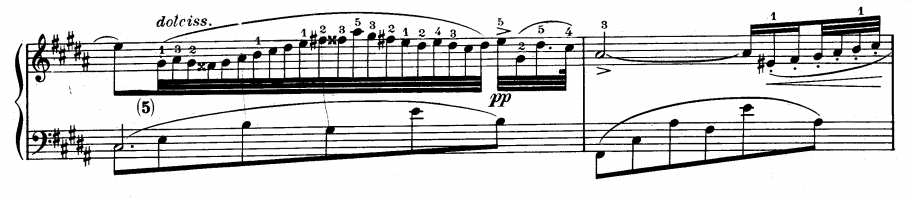

Published in 1835, the Op. 27 nocturnes are sandwiched chronologically between two monumental achievements in Chopin’s output: the 12 Etudes, Op. 25, and the 24 Preludes, Op. 28. We can easily hear how Chopin may have been inspired by bel canto singing, and some passages resemble the elaborate cadenzas that star singers would have performed in their arias, as in the example below.

Published in 1835, the Op. 27 nocturnes are sandwiched chronologically between two monumental achievements in Chopin’s output: the 12 Etudes, Op. 25, and the 24 Preludes, Op. 28. We can easily hear how Chopin may have been inspired by bel canto singing, and some passages resemble the elaborate cadenzas that star singers would have performed in their arias, as in the example below.

Nocturne Op. 37, No. 2 (G Major)

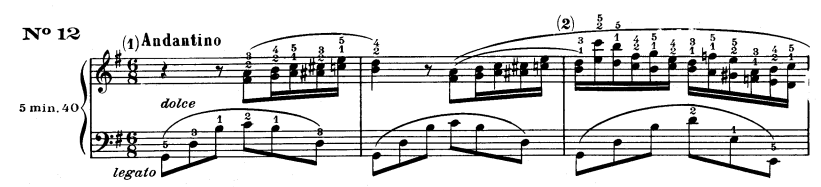

This nocturne is reminiscent of a barcarolle, a Venetian song sung by the gondoliers who paddle through the city’s famous canals. Like the barcarolles, which were timed to mimic the gondoliers’ strokes, this nocturne is in 6/8 time.

This nocturne is reminiscent of a barcarolle, a Venetian song sung by the gondoliers who paddle through the city’s famous canals. Like the barcarolles, which were timed to mimic the gondoliers’ strokes, this nocturne is in 6/8 time.

Nocturne Op. 48, No. 1 (C Minor)

The Op. 48 Nocturnes were published in 1841, amidst a particularly prolific time for Chopin. 1841 also saw the introductions of several freestanding works, including a Tarantelle, a Polonaise, the famous Prelude in C-sharp minor, the Allegro de concert, a Fantaisie, and the third Ballade.

The Op. 48 Nocturnes were published in 1841, amidst a particularly prolific time for Chopin. 1841 also saw the introductions of several freestanding works, including a Tarantelle, a Polonaise, the famous Prelude in C-sharp minor, the Allegro de concert, a Fantaisie, and the third Ballade.

Nocturne Op. 72, No. 1 (E Minor)

All of the Chopin opus numbers post-Op. 66 were published after the composer’s death in 1849 from a malady suspected to be tuberculosis. Despite being Chopin’s 19th published nocturne, Op. 72 No. 1 was his first compositional foray into that idiom. He wrote it in 1827, at 17 years old, and — as was the case with many of his posthumous works — he was never sufficiently satisfied with it to allow it to be published.

All of the Chopin opus numbers post-Op. 66 were published after the composer’s death in 1849 from a malady suspected to be tuberculosis. Despite being Chopin’s 19th published nocturne, Op. 72 No. 1 was his first compositional foray into that idiom. He wrote it in 1827, at 17 years old, and — as was the case with many of his posthumous works — he was never sufficiently satisfied with it to allow it to be published.