Ceiling frescoes by Antonio Maria Viani in the Sala degli specchi in the Palazzo Ducale, Mantua, Italy (Source: Wikimedia)

The Italian city of Mantua: the setting for Verdi's opera Rigoletto. The city of exile for Juliet's beloved in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. In the 16th century, Mantua was unrivalled in beauty, wealth, and sophistication. The gardens and courtyards of its ducal palace, each more magnificent than the one before, and its devotion to art, music, and literature, made Mantua, in the eyes of many, one of the most elegant and sophisticated cities in the world.

According to an ambassador from Venice who visited Mantua in 1588, the city had a population of around a quarter of a million inhabitants, and Jews made up one fifth of that population. Special taxes were levied on them for no other reason than the fact that they were Jews. They were members of a segregated population, forced to wear a yellow badge as a signifier of their race, forbidden from most areas of employment. They were subject to having property seized, forced to attend sermons about Christianity, and sometimes burned at the stake as witches for the benefit of visiting dignitaries.

Despite experiencing a deep decline in both the political and economic realms at the beginning of the first decade of the 17th century, Mantua remained one of Italy's greatest and wealthiest cities. This was due in no small part to Duke Vincenzo I Gonzaga, one of the most magnanimous patrons of the arts on all of the Italian peninsula.

Vincenzo I Gonzaga in ducal armor (Frans Pourbus the Younger, 1588)

The Duke's love for the arts, and acquisition and promotion of them, was due in no small part to his upbringing in Ferrara near his sister Margherita, the third wife of Alfonso II d'Este. Under the House of Este, Ferrara had become an internationally known capital, where economics, philosophy, and religious thought all flourished. The court's elaborate and virtuosic entertainments, the renowned balletto delle donne among them, certainly were a model for Vincenzo, who, on becoming Duke of Mantua in 1587, immediately set to work creating his own court of immense artistic wealth.

Along with founding a court orchestra, Vincenzo, who was, if truth be told, a bit of a spendthrift, collected as many sculptures, paintings, and other works of art as the palace could hold. Soon, Vincenzo's court was a magnet for Europe's leading artists, poets, and musicians: Peter Paul Rubens, Claudio Monteverdi, and Salamone Rossi Ebreo — the Jew — among them.

Vincenzo's relationship to the Jews of Mantua was neither cut and dried nor consistent. Although he had all foreign Jews exiled from the city in order to prevent an increase in the Jewish population, the Catholic Church accused the Duke of leniency towards Mantua's Jewish residents. This led to Vincenzo having to protect the Jewish community to a certain degree, to avoid a violent uprising against them. Yet, it was in 1610 that he established Mantua's Jewish ghetto. Jews already were living in restricted areas, but this new Jewish ghetto had a physical barricade. How then, to explain his invitation of Salamone Rossi Ebreo — Salamone Rossi the Jew — to his court?

The Fall of Giants, a fresco in the Hall of Giants located in the Palazzo Te in Mantova

Salamone Rossi's skill as a violinist and composer was highly valued at Vincenzo's Catholic court, and he was officially exempted from wearing the yellow badge required of the Mantuan Jewish community. But as a Jew, he still was seen as an interloper. It was solely due to the patronage of the Duke that Rossi achieved the status that he did, precarious as it was. As Don Harrán, Artur Rubinstein Professor Emeritus of Musicology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, points out, "As a Jewish musician working for the Mantuan court, and competing for the favors that its Christian musicians and composers hoped to gain, it was only inevitable for Rossi to have been considered an intruder. His talents as composer and violinist must have been so remarkable that Vincenzo and his successors decided to keep Rossi in their service over the course of almost forty years, from 1589 to 1628."

As early as 1476, Hebrew works had been printed in Mantua. But it wasn't until 1623 that Salamone Rossi's thirty-three Songs of Solomon (Ha-shirim asher li-Shelomoh) became the first composed "songs" to be published in Hebrew. Sebastian Gluck, pipe organ builder and considered the authority on the synagogue organ in America, points out that Rossi "…was the first to write Jewish liturgical music in the prevailing style of the time, without melodic or harmonic influence from Hebraic chant."

The title page of Rossi's Songs of Solomon, a collection of 33 songs published in 1623. Rossi set Hebrew liturgical texts in music styles of the time.

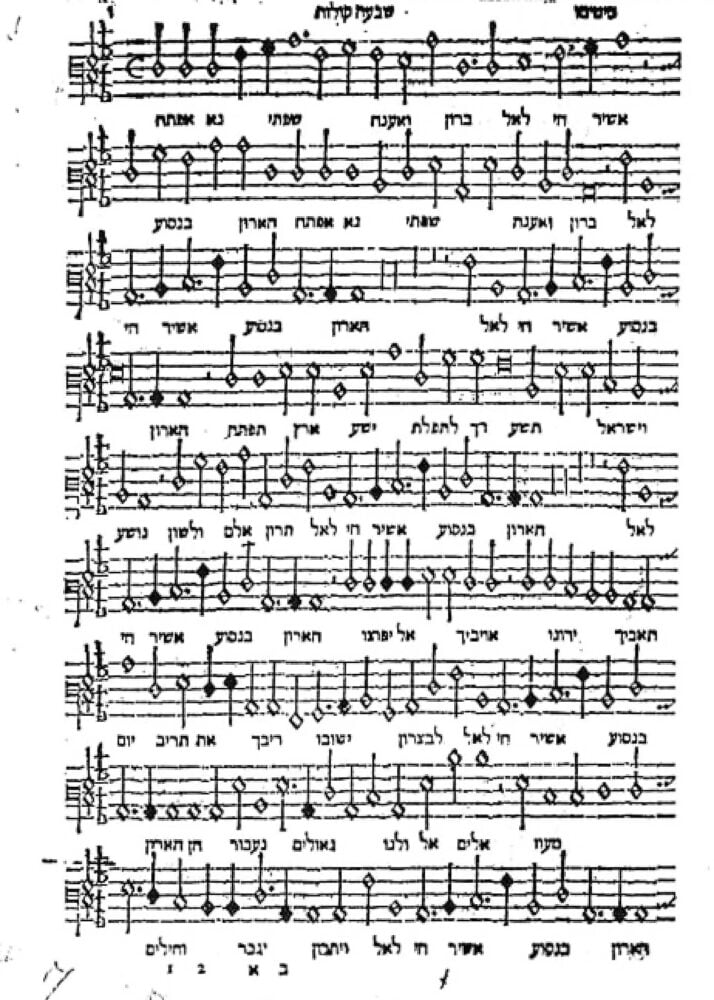

Rossi had to solve the problem of musical notation being written left to right and Hebrew being written right to left, which would have been challenging for musicians.

The songs use texts from the Psalms, Leviticus, and Isaiah, as well as non-Biblical Jewish sacred works. According to Elad Uzan, classical music critic of the Israeli daily Yedioth Ahronoth, "Rossi named his composition Songs of Solomon, presumably to link it to the legacy of the Song of Songs, traditionally believed to have been written by King Solomon. Alternatively, the title also might make the reader assume that Rossi dedicated his work to King Solomon (in fact, however, he dedicated this collection of songs to himself)."

Rossi's position in the court was not without controversy in the Jewish community as well. He set Hebrew liturgical text in the prevailing musical styles of the late Italian Renaissance, earning scorn from his fellow Jews. His secular madrigals and instrumental works, his role as court violinist and director of its 30 piece orchestra (he led the orchestra at the 1607 premiere of Claudio Monteverdi's L'Orfeo), and his encouragement of his sister, known as Madame Europa, the only female professional Jewish singer of her time, received varying degrees of tolerance from within his own community.

Rossi wasn't the only Jewish musician at the Gonzaga court, however. "Musician" was one of the occupations Jews were allowed to practice in Mantua in the early 17th century. The Duke of Mantua's payrolls from the period of 1577 to 1637 show many composers, singers, and instrumentalists with Jewish names, and all followed by the word "Hebreo," meaning "Jew."

Spanish Synagogue (or Schola Spagnola), Venice, established 17th century (Photo courtesy Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra)

Norsa Synagogue, Mantua, established 1513 (Photo courtesy Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra)

German Synagogue (Schola Tedesca) Venice, established 1528 (Photo courtesy Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra)

Though Rossi kept his position at the court, conditions in general for the Jews of Mantua continued to deteriorate. No records exist for either Salamone Rossi or his sister Europa after 1630. It's likely that they died during the Austrian sack of the Mantuan ghetto, either by plague or by slaughter.

For further reading

Harrán, Don: Salamone Rossi: Jewish Musician in Late Renaissance Mantua: Oxford Monographs on Music, 2003

Idelsohn, Abraham Z.: Jewish Music in its Historical Development: Henry Holt, 1929