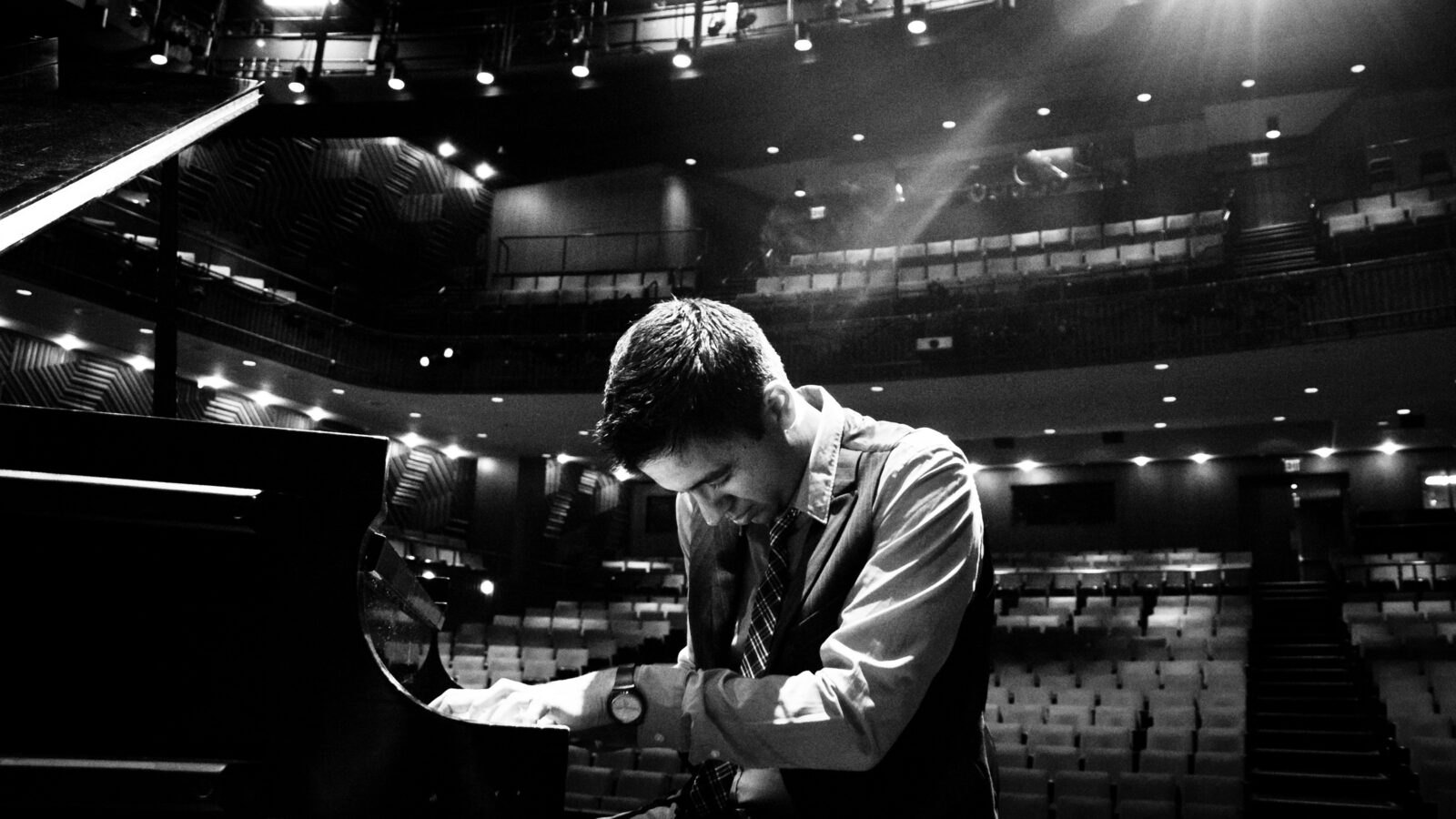

Vijay Iyer (Photo: Lena Adasheva)

DownBeat magazine gave Vijay Iyer the honors of Jazz Artist & Jazz Group of the Year in its 63rd Annual Critics Poll. But to Iyer, jazz is a bit of a four-letter word.

“A lot of the great musicians had an ambivalent or critical distance from the word jazz,” Iyer said in a recent interview.

Despite having ambivalence towards the word “jazz,” he’s received high honors for work that many would describe as “jazz,” including a 2013 MacArthur Fellowship. In 2014, he joined the faculty of music at Harvard University.

“The word ‘jazz’ is basically an invention of the record industry and it persists more as a business term rather than any real description of anything actually happening musically,” he said. “The label is a little bit arbitrary.”

Iyer’s recent album, Break Stuff, has received high praise from Rolling Stone, the New York Times, and National Public Radio. Most reviews tend to use the word “jazz” somewhere in the description, even if qualified to say Iyer “expanded the boundaries of jazz,” as did NPR.

“The word ‘jazz’ is a tenacious way of framing and stereotyping the actions of musicians and describing what they do,” Iyer said. “From Duke Ellington to Charles Mingus to Miles Davis, they all rejected the word. They had no use for it. John Coltrane said in an interview, ‘Jazz is a word they use to sell our music, but to me that word does not exist.’ That’s a direct quote.”

“That’s not how everybody feels about it,” he conceded. “Some people embrace the term. Some people work with it. Some try to change what it means. Others will just reject the term. What these different reactions should tell you is that the term doesn’t mean anything.”

Iyer thinks one problem with the term jazz is that it often describes people more than the music itself.

“When we’re talking about genre,” he explained, “we’re not really talking about musical style, we’re talking about communities. So what we have here are communities that exclude each other, or communities that get excluded by others.”

A “Creative” Alternative to the Term “Jazz”

Many musicians, including Iyer and some of his mentors, prefer to describe their work as “creative music.” Iyer said, “I’ve been very lucky to have a lot of friendships, mentorships, and apprenticeships with members of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM).”

“In 1965 on the South Side of Chicago a group of African American, creative musicians formed an association to support their own endeavors so that they could carry out their own projects with autonomy and empowerment, to build community around their own music making, and to create a kind of mobility that transcended these conventional notions of genre. Even the terms ‘creative music’ and ‘creative musicians’ were created as a way to push back against ‘jazz,’ which has historically and continues to be a limiting term to describe what these people do.”

AACM members with whom Iyer has worked include Henry Threadgill, Roscoe Mitchell, Wadada Leo Smith, and Muhal Richard Abrams.

Iyer has been particularly close with Chicago-born composer, musician, and longtime AACM member George Lewis. “I met George over 20 years ago, and we’ve been in constant interaction ever since. He’s been my mentor as a scholar, musician, and composer, and he’s also been a good friend and collaborator.”

Lewis’s written history of the AACM, A Power Stronger Than Itself, mentions that many creative musicians of color suffer from what he calls the “one-drop rule of jazz.”

Many creative musicians are labeled “jazz” musicians out of convenience, while he writes that “musicians of other ethnicities have historically been free to migrate conceptually and artistically without suffering charges of rejecting their culture and history.”

Iyer agrees that the “one-drop rule certainly afflicts African American artists. My own relationship is more complicated. I’m South Asian American. As far as American music goes, I seem to be between categories. That’s how I’m always seen. I’m usually described as ‘outside’ of whatever someone seems to be talking about. That part of my experience is a corollary to what George is talking about.”

Iyer’s Latest Creative Endeavor

In March of 2016, Iyer will release a recording of a new work, A Cosmic Rhythm with Each Stroke, commissioned by Metropolitan Museum of Art’s LiveArts for the exhibition dedicated to Indian modernist Nasreen Mohamedi.

Iyer described Mohamedi as a “really interesting artist who did ink on paper drawings that have a mystical, almost other-worldly quality to them. There’s a lot of space in her work, a lot of patterning, a lot of fragility, a lot of repetition, a lot of mystery.”

“I am sharing the commission with Wadada Leo Smith, and we created collaborated work inspired by her. Not just her work, but also what we know about her as a person, particularly through her diaries. One phrase that stuck out to me from those is ‘the maximum from the minimum,’ and it became some kind of stimulus for the work.”

Iyer said that he and Smith, who have collaborated for a decade, “transcribed the visuals into a score that we then played. We tried to get between the lines, in a way. It’s a tribute to her. It’s not a translation. We’re trying to play beyond the page.”

Smith happens to be an accomplished visual artist himself, whose work was recently displayed at the Renaissance Society in Chicago. Iyer said, “Wadada created a score in his own way, which is very colorful in contrast to her own work that was drained of color later in her life. That was his way of meditating on her spirit.”

Iyer said that in A Cosmic Rhythm with Each Stroke, “you’ll hear patterning and cycles, but you’ll also hear cycles fracture and disrupt each other, and lastly this electric spirit emerging among these shards of structure.”

To learn more about Vijay Iyer, visit his website.