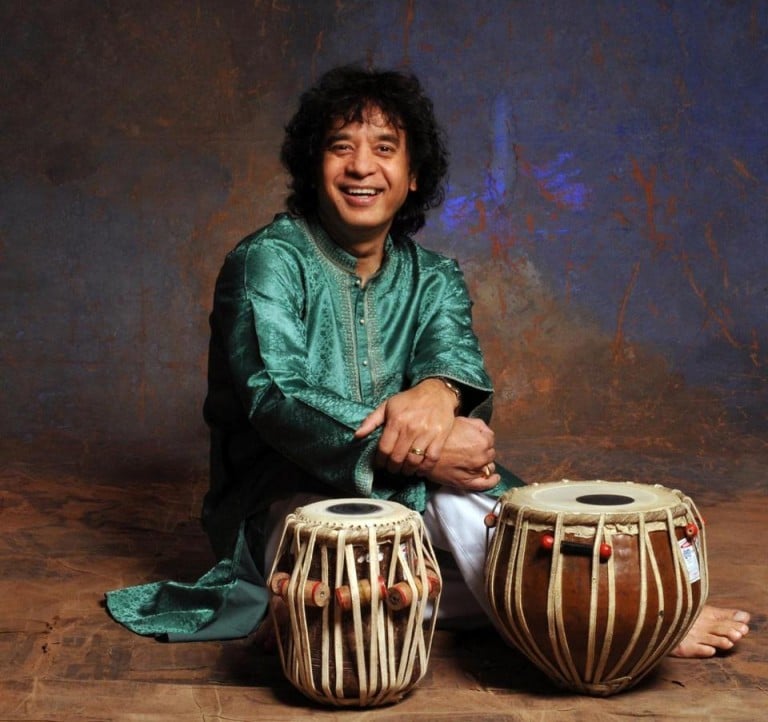

When Zakir Hussain, one of the world’s greatest percussionists, speaks about his childhood in Mumbai, it’s easy to understand how his career has led him to collaborations with diverse artists from Ravi Shankar to Yo-Yo Ma to Mickey Hart of the Grateful Dead.

“Every day I grew up studying the Quran, singing Christian hymns, and playing Hindu devotional music,” Hussain said in an interview before an appearance at Chicago’s Symphony Center. “India is an interesting concoction of so many different cultures – Christian, Buddhist, Islamic, Hindu – all coexisting and working in a unified way.”

Hussain’s early education is a testament to India’s diversity. “When I was a young wee lad, like 7 years old,” he said, “I would learn the language of the tabla with my father from about 3:00 in the morning until 6:00 in the morning.”

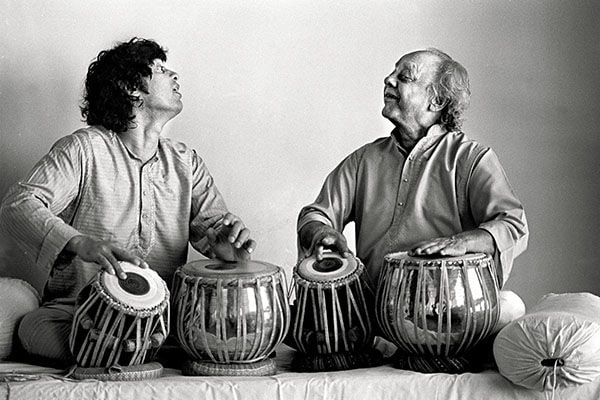

Lucky for Hussain, he could not ask for a better instructor than his father, the great Alla Rakha, Ravi Shankar’s long-time collaborator who popularized the tabla around the globe.

After three hours of studying Indian music, “which is connected to Hindu divinity, I would have my breakfast and go and read the Quran. After I would cross the street to my school, St. Michael’s, and sing Christian hymns. Then after that I would go home late in the day and practice more tabla.

“I grew up with all of these ways of life and never was I aware for any moment that they were any different or separate from each other,” he said. “None of the fathers or nuns ever imposed a Catholic way of life. No Islamic mullah ever said theirs was the only way to go. No Hindu ever told me I had to pay respects to Lord Krishna or Lord Siva if I played music in a temple. It was all part of one way of thinking.”

Despite India’s diversity, Hussain expressed frustration that, “if you go into some parts of the United States and people still feel like cows and elephants are our modern transport. Information is not distributed equally around the world.”

Now based in San Francisco, Hussain also expressed frustration by the ways different cultures interact in the United States, particularly during the 2016 presidential election. Donald Trump, in his campaign for the Republican nomination, has said, “Islam hates us.”

In response to Trump’s comments, Hussain said, “There are some people who believe in isolation and others who believe in inclusion, and they are both starting to express themselves. It’s interesting – there are an incredible number of people who believe in inclusiveness.”

One of the biggest problems in the United States today, according to Hussain, is that “the needs of a few have come to determine the needs of the many,” Hussain said. “I think the people of the United States are missing the point. It’s not about your way of life. It’s how to balance the budget and how to create economic growth.

“In India, the government steps back and let certain fanatical elements of both the Islamic and Hindu systems to fight among themselves,” he explained. “Some people are talking about intolerance, but the government isn’t doing anything about it. In the United States, the same thing is happening. People are just getting into fisticuffs amongst each other, and not in any way calming things by taking the whole religious element away from the selective process.”

Zakir Hussain learns from the master, his father, Alla Rakha

Ideas about cultural tolerance and inclusion have naturally influenced the way Hussain makes music.

“My father grew up in a very different time,” he said. “He learned in a very traditional, very classical, very straight-forward way. He wanted to practice and teach the music in its purity. But by the time he came to me, he had arrived in Mumbai and started working in the Bollywood industry as a composer.”

Even after India gained independence in 1947, Portugal still occupied Goa. One of the benefits of imperialism, in this case, was the opportunity for exchanges among musicians of different backgrounds.

“Many musicians of Portuguese origin would come there, playing saxophones and horns and trumpets and violins. They all played a role in the development of the Bollywood industry. My father got to know them and started to work with them, and his mind started expanding. Then he and Ravi Shankar started traveling as a duo in the 1950s, and his mind really opened. I profited from all of that.”

Hussain said, “I did not get the kind of isolated teaching that my father received. He was more open, more universal, and more inclusive of everything that was around him. He had a vision that I would be interacting with all kinds of musicians all over the world, so that I should have a lot of tools to work with.”

Rakha prepared his son well. “When it came time for me to work with South Indian musicians, or jazz musicians, or rock musicians, or hip hop artists, and also when I started playing in Bollywood music, it became much easier to expand or contract what I needed to include in the music based upon the space allotted to me.”

Since his early days studying with his father in Mumbai, Hussain has gone on to work with some of the greatest musicians of our time in nearly every genre and style imaginable.

“I am fortunate that I came into contact with musicians who were sympathetic to the Indian way of thinking,” he said humbly. “George Harrison was already studying with Ravi Shankar. John McLaughlin had already studied veena. Charles Llyod was very deeply interested in Indian spirituality. Yo-Yo Ma is already from that part of the world. When it came to Mickey Hart, the rhythm was our deep connection.”

Hussain said that all of his collaborators, no matter their background shared a similar quality.

“All were great masters because they understood this: mastery is not the important part of playing music, being a student is the most crucial element of being a musician. When I worked with all these musicians, they took me into their world, and I learned from them.”

One of his most curious collaborations is, no doubt, a triple concerto for tabla, banjo, and double bass called The Melody of Rhythm which he created and performed with Béla Fleck and Edgar Meyer.

“The piece evolved from many rhythmic patterns and ragas that I opened up to them, to which they added melodic ideas. Finally, Edgar added his magic by adding orchestral parts.” The three recorded The Melody of Rhythm with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Leonard Slatkin.

Hussain said at first, the project was met with criticism. “People would ask, ‘What are you guys going to do together, how is it going to be musical?’ But we were nominated for a Grammy that year,” he said proudly.

“It was a great learning experiencing and now I am writing music for tabla and orchestra,” he said. “Since that project I’ve written two concertos. One premiered at the Kennedy Center with the National Symphony Orchestra, and the other just premiered in India and Switzerland, which is just tabla and orchestra. It plays in London at the Royal Festival Hall in May.”

One of the most decisive influences on Hussain’s music-making, however, has been Bollywood, much like his father who learned about new musical traditions by working with Portuguese musicians in the film industry.

“If you play a raga, it requires that you express yourself over a long period, maybe even over an hour,” he said. “But in the film industry, if you have a 20-second scene, you need to express the emotion of the scene and what the scene is trying to do very quickly. Being forced to do that makes you a better technical performer on the stage. But working in Bollywood, the expressive quality of my music also changed.”

In Saaz, a film about the lives of legendary singers Lata Mangeshkar and Asha Bhosle, Hussain not only created music for the score, he also stared as an actor. Listen to some of the music below.

Even when Hussain is not playing for films, he said he tries to “create visual effects in my head of what I am playing, and bring the audience a little closer to me in my performance. You start to see music not just as a tonal experience, but as a multi-sensory experience.”

When working with students today, Hussain tries to teach the same open-mindedness his father encouraged.

“Some have a difficult time coming to Indian classical music,” he said, “because they always think of these traditions as being so old and so rigid in their principles that they become nervous when approaching them. People think they need to be in a certain state of mind or discipline to learn the music.”

“But I tell students that, ‘tabla is just another instrument. Learn it like you would any other instrument. Play it the way you want to play it, and eventually your relationship to the instrument will deepen. The instrument will reveal itself and tell you how else you can approach it.’”

To learn more about Zakir Hussain, visit his website.