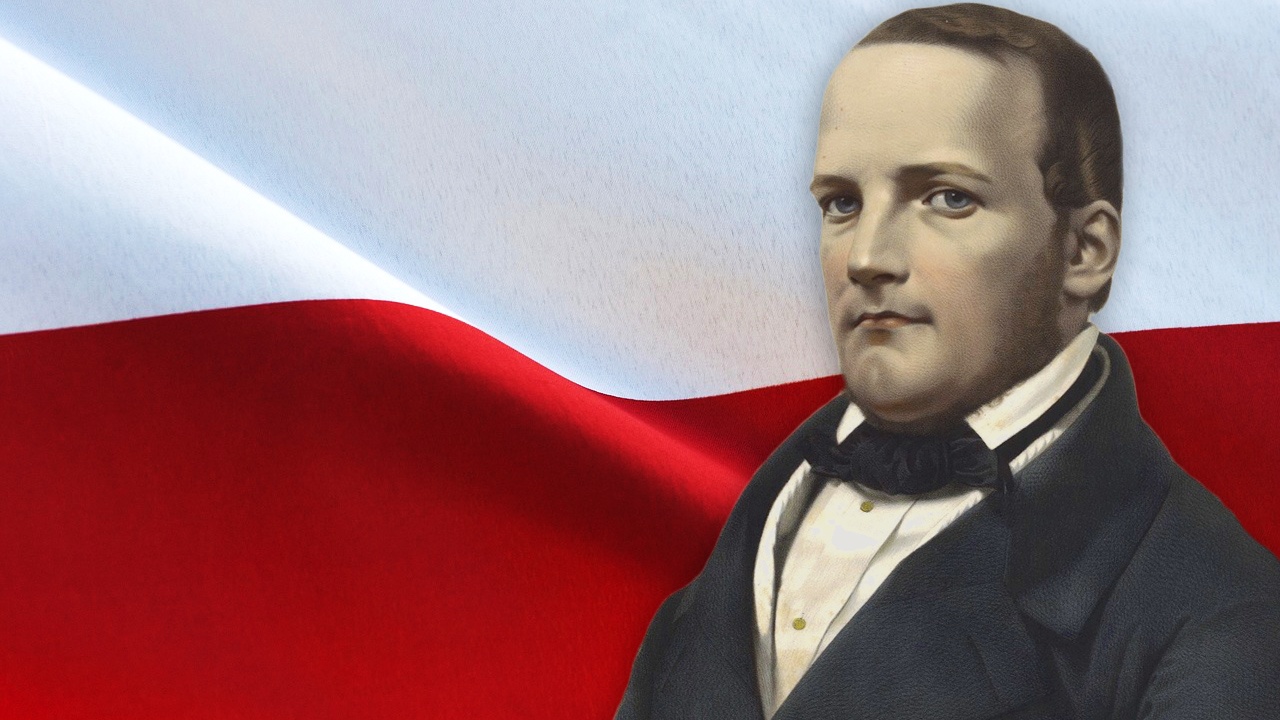

The name Frédéric Chopin is synonymous with Polish music and culture. But though Stanisław Moniuszko may not be a household name today, the composer is literally the face of Polish opera. A statue of him rests outside of the Warsaw Opera House, where he served as director and premiered several of his works.

The name Frédéric Chopin is synonymous with Polish music and culture. But though Stanisław Moniuszko may not be a household name today, the composer is literally the face of Polish opera. A statue of him rests outside of the Warsaw Opera House, where he served as director and premiered several of his works.

But who was Moniuszko? Stanisław Moniuszko (1819-1872) was born in Ubiel, now in Belarus. In 1828, his family moved to Warsaw, where he heard Polish folk music for the first time. He traveled around Europe during his adult life, meeting with and learning from the greatest opera composers of the day. Glinka, Liszt, Mussorgsky, and Rossini all recognized his talent. He spent the latter part of his life in Warsaw when he was appointed the director of the Warsaw Opera House in 1858.

His most well-known operas, Halka and Straszny Dwór (The Haunted Manor), are famous for their nationalistic elements, both musically and thematically. Like Chopin’s music, many of Moniuszko’s melodies are inspired by Polish dance music, such as the mazurka and polonaise. Moniuszko’s operas also depict the strength of the Polish people and military.

Listen to an example of a mazurka from The Haunted Manor below.

While the nationalism in The Haunted Manor united Poles, it upset others. In 1865, the year of the opera’s premiere, Russia controlled Poland. Eventually, Russian authorities banned the opera altogether. Since Poland’s sovereignty and culture were suppressed throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, Moniuszko’s operas are praised by the Polish public today.

To honor Moniuszko’s legacy, the International Stanisław Moniuszko Vocal Competition was founded in 1992 and takes place every 3 years. This year’s competition attracted 329 entries from 22 countries. A selection panel chose 89 singers to compete in the first stage. Over the course of 4 days, a jury consisting of world-renowned opera singers and casting directors eventually selected 16 singers to appear in the third and final stage of the competition. Each finalist had the opportunity to sing with the Polish National Opera Orchestra on the stage of the Teatr Wielki—Opera Narodowa (Grand Theatre—National Opera).

During the first and third stages of the competition, contestants were required to select a Polish-language work. This requirement created challenges for both native Polish and non-Polish musicians alike.

Countertenor Jakub Józef Orliński received Second Prize in the male category. A native of Warsaw, Orliński currently studies at The Juilliard School and was recently named a Finalist at the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions. Luckily for Orliński, who had difficulty finding Polish countertenor repertoire, the competition allowed for contestants to transpose Polish-language works.

“For the first round, my pianist, Michał Biel, actually forced me to sing ‘U jeziorecka’ by Szymanowski,” Orliński said. “We transposed it, and it sounds great for a countertenor. This music is just beautiful and it makes a really nice impression. We’ve also been performing it in New York, and everyone loves it! So we decided to use it for this competition.” He confessed, “It’s difficult to sing in my hometown because there a lot of expectations, and it’s pretty stressful. I was so happy to advance and to sing on the stage of the Teatr Wielki for the first time.”

The 2016 International Moniuszko Competition Finals in the Teatr Wielki-Opera Narodowa in Warsaw, Poland

For soprano and finalist Jacqueline Piccolino, a Chicago native who appeared on WFMT’s Introductions at age 18, familiarizing herself with the Polish language was a major focus of her competition preparation. “I am actually 25% Polish, but it took me about a month and a half to work on the language with a teacher at the University of Illinois, where I studied,” Piccolino noted after her performance in the final stage. “We talked about Polish customs and culture, and we went through the texts. It began to feel natural for me.”

She also enjoyed singing at the Warsaw Opera House because “it is a totally different thing than the American houses. It’s a smaller, intimate space. The audience is so enthusiastic about Polish music and music in general, and it’s fun to sing for them.” Piccolino sang the recitative and aria “Paria! On Paria!” from Moniuszko’s opera Paria in her final performance. “I’ve sung Chopin songs before,” she commented. “What I found after singing Chopin and Moniuszko is that both are brilliant composers, but Moniuszko has more of a dramatic flair. You can tell there is a very Slavic feel in his music, and he’s just excellent.”

Moniuszko’s works are not the only lesser-known repertoire performed at the competition. In a press conference the day before the final stage, members of the jury stated that because the competition already requires Polish works, contestants tend to branch out from the standard repertoire. Since the competition was also streamed online, countless people around the world were exposed to these diverse vocal works as well as tomorrow’s up-and-coming opera stars.

Moniuszko might not be a recognizable name yet, but his legacy is reaching beyond Poland now more than ever.

Michael San Gabino’s travel to Warsaw, Poland was sponsored by the Study Visits Department at the Adam Mickiewicz Institute. For more information about the International Stanisław Moniuszko Vocal Competition and a complete list of winners, visit their website.