Trey Graham was looking forward to an evening of truly fine music. It was 1995, and Trey, a young arts journalist in Washington DC, found his seat at the ornate Kennedy Center. Taking the stage tonight was opera singer Jessye Norman — “probably the grandest diva of that decade,” says Trey.

Trey Graham was looking forward to an evening of truly fine music. It was 1995, and Trey, a young arts journalist in Washington DC, found his seat at the ornate Kennedy Center. Taking the stage tonight was opera singer Jessye Norman — “probably the grandest diva of that decade,” says Trey.

There were some big classical works on the program, including song cycles (sets of several consecutive songs that all go together as a group) by Poulenc and Messiaen. And Trey, as a classical music aficionado, had very clear expectations about when the audience was supposed to clap.

“They would normally sit and listen to the whole set of songs, and then give a reaction … after that set was concluded,” he explains. But this night did not go as expected. “It was crazy pants,” says Trey with a laugh. “Every single set got interrupted by applause after each song… That’s a lot of applause, and not a lot of music!”

Trey was infuriated. The Kennedy Center crowd should know better, he thought. So after the concert, he submitted an op-ed to the Washington Post.

“Jessye Norman gave a recital so glorious as to leave no doubt that Washington is cosmopolitan enough to attract the best and brightest of classical musicians. Yet most members of the glittering audience at the Concert Hall behaved like the coarsest of groundlings — noisily rustling the pages of their programs, coughing consumptively enough to do Violetta justice, even interrupting one song with applause before Miss Norman’s accompanist had struck the final chord.”Trey Graham (Washington Post, April 23, 1995)

Today, Trey winces when he reads that letter. “This is such a piece about establishing the difference between me and the other people in the audience, that it’s almost embarrassing to read,” he says.

In the letter, Trey comes off like a well-known stereotype: the monocle-wearing classical music snob, sneering down at the common people. But what is the story behind that stereotype? Why is there a correct way to act, to dress, and — especially — to clap in the concert hall?

These rules and traditions may seem second-nature to classical music fans. But do they still make sense in the twenty-first century?

From rowdy to reverential

Mozart Family Portrait. Oil Painting by Johann Nepomuk della Croce. Original owned by the Mozarteum, Salzburg.

Experts on concert hall etiquette like to talk about a famous letter from Mozart to his father, dated July 3, 1778. The composer is telling his father about the previous night, when he’d conducted his 31st symphony for the first time.

“And in the midst of the first allegro came a passage I had known would please,” Mozart writes. “The audience was quite carried away – there was a great outburst of applause.” In the last movement, there’s yet another burst of clapping. Mozart was thrilled. He writes: “I was so happy that I went straight to the Palais Royale after the symphony, ate an ice cream, said the rosary I had vowed — and went home.”

If you’ve seen a live orchestra, you may recognize how strange this is. Today, it’s a faux pas to clap even between movements, let alone while the orchestra is playing. So why was Mozart so happy they were interrupting his brand new symphony?

“The backdrop here, though, is that concerts in the late 18th century were not concerts in the modern sense,” says Christina Bashford, a professor of musicology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “Music often served as background to social interaction, and not everybody necessarily wanted to listen, or listened all the time.”

For hundreds of years, Bashford explains, most new music had been supported by patrons. Composers would find wealthy families who could pay them a stipend to write music for their private events and balls. And since they were paying for it, these patrons and their guests could act however they wanted. Written records from Mozart’s time describe people who come in halfway through the concert, only to talk, drink, and carry on over the music. That being the case, it’s no wonder Mozart was happy to hear applause—he was probably just glad that the audience was paying enough attention to respond at all.

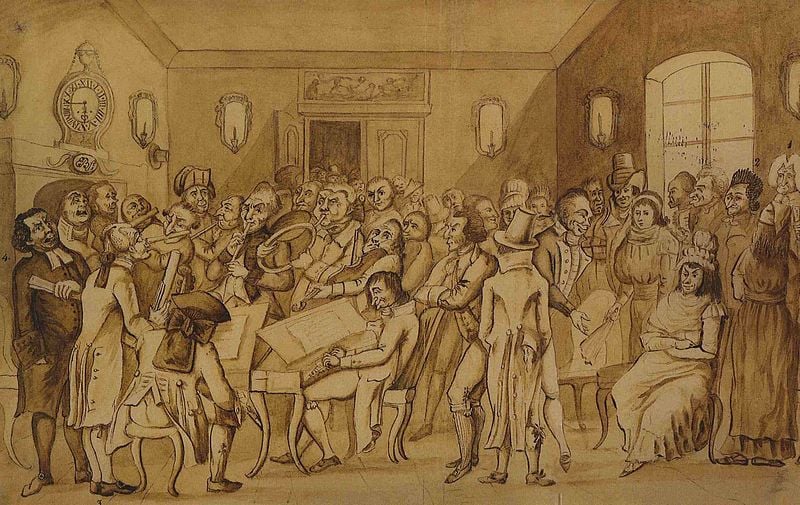

A collegium musicum performs in the late 18th century (Emanuel Burckhardt-Sarasin)

Yet this well-heeled world was starting to change. “Composers from sort of the 1810s, 20s onwards start to function … in a much more sort of freelance way,” says Bashford. “So music starts to become this sort of commercial good.”

That is, in order to make a living without patronage, composers now suddenly needed to sell tickets. As a result, Bashford says, concerts opened up to the public, to people from all across the social spectrum. In a world without recorded music, this was an exciting development. “You might have only one chance in your lifetime to hear Beethoven’s 6th symphony,” she says. This might be why music historians have observed that composers from this time were suddenly being treated with much greater reverence.

Bashford cites an example from the 1840s in London. “There was an institution called the Beethoven Quartet Society that produced an extraordinary set of programs for its members,” she says. “And emblazoned on the top were the words, ‘Honor to Beethoven.’ That respect for composers and their music soon started to affect concertgoers’ behavior as well. According to Bashford, concert programs from this era would often feature phrases like, ‘The greatest honor you can pay to music is to listen in silence.’ People are not just quiet but very reverential, almost meditative, in how they approach this experience of listening to music,” says Bashford.

At the same time, ornate, bespoke concert halls were being built. And as going to concerts began to feel more and more like going to church, there were new expectations for concertgoers. They were now expected to dress up, to arrive on time, and not to interrupt the music with vulgar applause.

Over the next 50 years or so, this etiquette became more and more entrenched, until it was practically the law of the land. But with so many rules to separate the in-crowd from the out-crowd, a particular stereotype began to emerge: classical music was increasingly seen as a part of exclusive, upper-crust culture, not meant for common people.

Overcoming the stereotype

Joseph Haydn playing quartets (Anonymous, before 1790.)

Tim Hankewich has conducted Orchestra Iowa for the last decade. In that time, as much of his core audience has gotten older and passed away, one of his biggest challenges has been simply filling seats. “So we have to ask ourselves, ‘Well, who else can we reach out to? Who are the constituencies that would be inclined to come, but aren’t coming, and what’s keeping them at bay?’” says Tim.

One answer: alienation. Tim worries that those who don’t know the rituals of the genre may be afraid of doing something wrong, and thus will stay away from concerts.

Even Tim — who has his doctorate in conducting — has felt that alienation. He recalls being in the audience for a concert where the director had specifically asked the audience not to applaud at the end, on account of the serious themes of the repertoire. But Tim forgot. “And then I started applauding as the only person in that room,” he says. “It seemed like the entire world’s eyes were darting at me, and I just wanted to crawl under my seat.”

Ever since, Tim has made a point to make his concerts welcoming. Last year, his orchestra did Rodion Shchedrin’s zany adaptation of Carmen. The suite is rife with bizarre, over-the-top passages. So, at the concert, when he introduced this piece, Tim specifically instructed the audience to react however they wanted to, even if they feared it broke the rules of the concert hall. “I was inviting the audience to laugh and to smirk and to chuckle and even to clap if they felt like it,” he recalls.

The audience members acted accordingly. “There was one movement that was very tender … and was ending very quietly and beautifully,” says Tim. “And then at the end, the composer put on this extremely loud, rude chord.” The chord was so incongruous with the previous section that the audience couldn’t help but laugh. “And I could actually hear that laughter coming to the stage,” says Tim. “And the musicians were feeding off that because … the musicians knew that the audience was getting the joke.”

The audience seemed to enjoy the experiment. But if norms like silence function to keep music in the realm of the sacred, then is something valuable lost when we intentionally defy them? Tim Hankewich thinks so.

“You know, one of questions I’m always asked is, ‘Do I need to dress up?’ And the answer is, of course not. But at the same time … it’s also nice to go out dressed really well,” he says. “Because there’s beauty to the formality of it. … And it shouldn’t always be cast with dispersion.”

And so we find the classical music world stuck between two polarizing choices: To conform to an arcane, alienating set of rules, or to treat classical music with less respect and abandon the sacredness of the concert.

Which will it be? That’s for a new generation of classical music fans to decide.