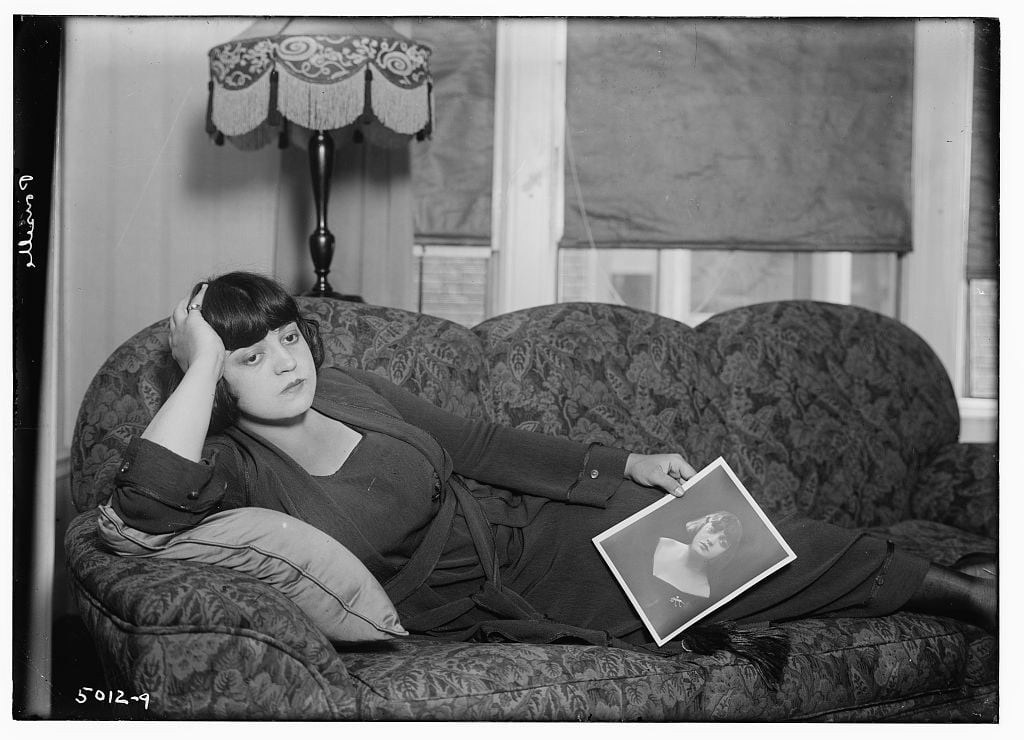

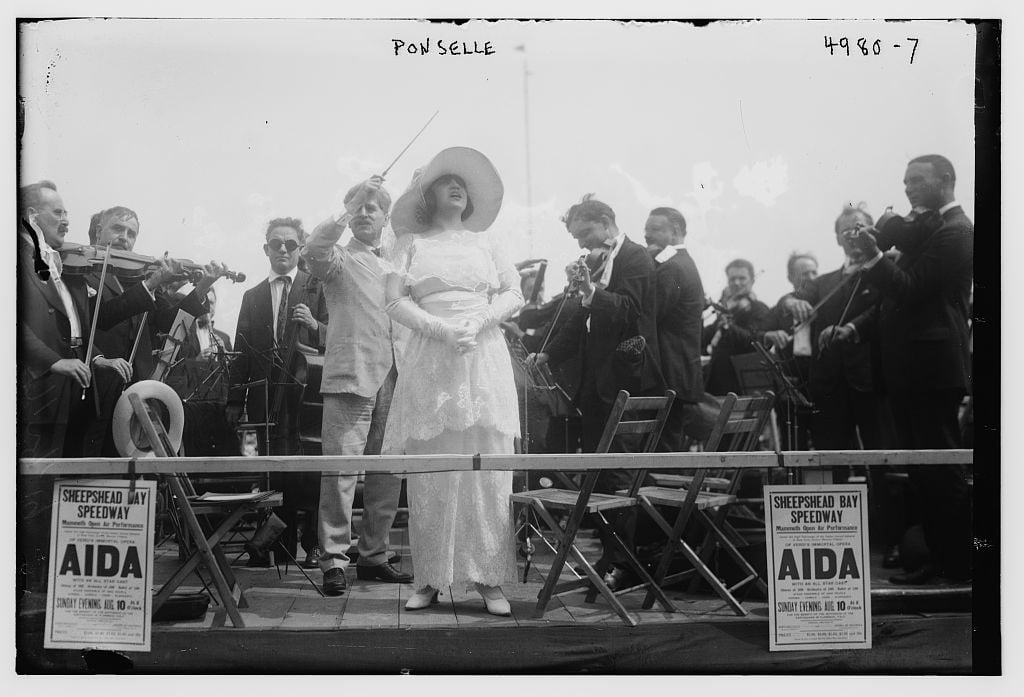

Rosa Ponselle in 1919 (Photo: Bain, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

A seemingly medieval castle overlooks the town of Meriden, Connecticut, where crystal waterfalls tumble down stony hillsides. Roads wind through panoramas of color that seem to stretch into endless natural splendor. This is where the great soprano Rosa Ponselle, whose voice has been described as one of the “most beautiful of the century,” was born.

Meriden, like many towns and cities in Connecticut at the turn of the 20th century, was home to a number of Italian immigrants – including Rosa’s parents. She first studied singing with her mother and gave her first public performances in churches. However, it was not long before Ponselle was sharing her talents on much larger stages.

West Main Street, Meriden, CT (Photo: John Phelan, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

But the first person in the Ponselle family to start a career as a performer was Carmela, Rosa’s elder sister. Carmela moved from Meriden to New York City where she performed on Broadway in the musical The Girl from Brighton. Although the city was just about one hundred miles away from their home in Connecticut, they were, culturally, worlds apart. New York was quickly becoming one of the world’s most populous cities, and a place where the right combination of talent, hard work, and luck could give your career a jump start.

A postcard of Craig Castle (Tichnor Brothers, Publisher, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Rosa eventually followed her sister to the Big Apple. The two had a duo act billed as the Ponzillo Sisters and were called “Those Tailored Italian Girls,” though Rosa also appeared in films and vaudeville acts independently, as well. How Rosa’s career developed afterwards is nothing short of a fairy tale, a dream-come-true for any musician. (Quite conveniently, Rosa is still being called “the greatest fairy-tale figure in American opera.”)

Rosa studied voice with William Thorner, who brought her to the attention of the famous tenor Enrico Caruso. Impressed by Rosa’s voice, which had a range of nearly three octaves – huge and rich, Caruso arranged for her to audition with Giulio Gatti-Casazza, who was then the manager of the Metropolitan Opera and who had formerly managed La Scala in Milan. Rosa was offered a contract to sing opposite Caruso in a performance of Verdi’s La forza del destino, marking both her operatic debut and the opera’s premiere at the Met.

The 21-year-old Rosa, from the small town of Meriden, was standing on the awesome stage of the Metropolitan Opera. She had seen only one opera and had next to no training, but was now in the midst of her first operatic performance as Leonora.

This photo of pianist Josef Hofmann performing at the Metroplitan Opera House offers a glimpse of what Rosa might've seen when she made her operatic debut on the same stage (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

What followed was a career without equal. In 19 seasons, she performed 22 roles, in Oberon, Ernani, Don Carlos, La Gioconda, William Tell, Don Giovanni, and La traviata, just to name a few. A lot of roles, but never any Puccini or Wagner. She was especially celebrated for her performances in the title role of Bellini’s Norma.

And as there must be shadow where there is light, not all of Rosa’s performances were adored by the critics. In 1935, she made her role debut as Carmen, one that the New Grove Dictionary of American Music described as being her only true failure and one she attempted “perhaps unwisely.” Was it unwise? Listen to her perform music from Carmen in a screen test below and decide for yourself.

However, there was a golden thread woven through the fabric of her whole career: Her wish was law. In The Met: One Hundred Years of Grand Opera, Martin Mayer recounts that Rosa “hated steam heat, and would feel the pipes on stage as she entered the theater before a performance, so everyone shivered in the drafty old house, winter afternoons and evenings, when Ponselle was to sing.”

Before she would attempt to sing her role in Norma, she insisted that the pitch of the Met would be reduced from A=440 to A=435. Because the difference is an almost inconsequential fifth of a semitone, “the purpose must have been entirely psychological,” Mayer suggests. Again, her wish was law.

(Photo via The Library of Congress on Flickr)

Luckily for music lovers today, Rosa and the recording industry were born in the same era. So, on whatever pitch she decided to sing, we are able to admire her artistry nearly 100 years later.

You can hear the voice of Rosa Ponselle in a two-part program of Arias and Songs. Listen to Part I here, and tune in for Part II on Saturday, December 2, 2017 at 4:30 pm.