In 2007, nearly 1,400 guitar players gathered in Welles Park to help Old Town School set the record for the world’s largest music lesson (Photo courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music Resource Center & Archives)

Over the last sixty years, the Old Town School of Folk Music has grown from humble beginnings to become the largest nonprofit community arts school in the United States.

With this Chicago gem celebrating its diamond anniversary, we mined the archives and discovered a rich cache of historic photos, as well as an inspiring collection of oral histories from some of the many people who created, influenced, and sustained the legacy of Old Town School.

On a frigid night in December 1957, 150 students inaugurated a new kind of music center where they learned songs by ear as well as the techniques to accompany themselves on traditional instruments. Then as now, the instructors were a combination of highly skilled amateur and professional musicians who encouraged music-making in a social, informal environment.

Studs Terkel and the audience on opening night (Photo: Kiko Konagamitsu, courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music Resource Center & Archives)

Reflecting on these “roots and the remarkable culture that they nurtured,” executive director Bau Graves describes some of the changes that have taken place since then. In the beginning, he observes, “Old Town School represented a small community of folkie activists. Today, there are dozens of ethnic and aesthetic communities that find common cause in our programs.”

Upwards of 7,000 people participate in hundreds of different classes each week. While scores of teachers still provide offerings like guitar and fiddle, the school has diversified, expanding to include world music, dance, ensemble performance, groups for teens, Wiggleworms for toddlers, festivals, and outreach programs. Musicians from around the globe perform 400-plus concerts per year in a variety of venues across the city.

Six decades on, what continues to set the Old Town School of Folk Music apart is the philosophy that music is about a human connection, and that it is for everyone no matter your skill level, age, or cultural heritage. There are so many stories to tell. Here are just a few.

The Birth of the Old Town School

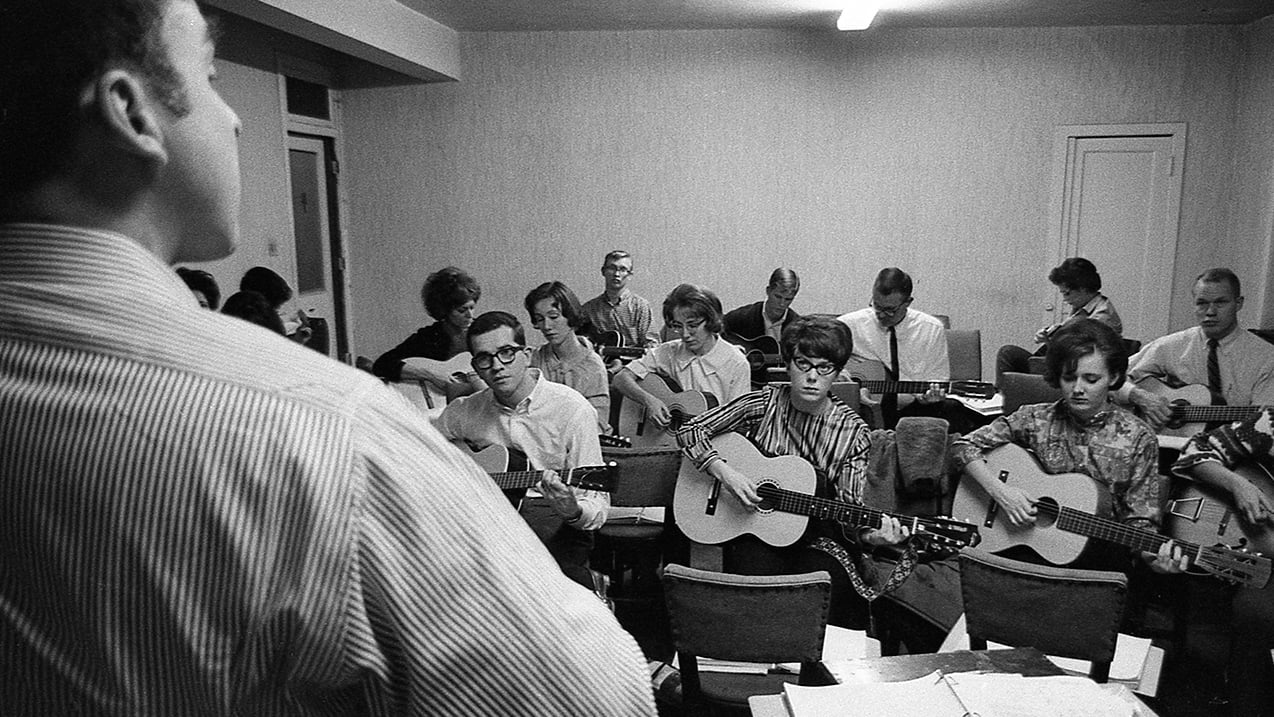

Ted Johnson leading one of the first Old Town School guitar classes (Photo: Kiko Konagamitsu, courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music Resource Center & Archives)

Ted and Marcia Johnson fondly recall the Chicago music scene in the late 1950s, and the confluence of events that led to the creation of the Old Town School of Folk Music. A touring musician named Frank Hamilton had a regular gig at the nation’s first folk-centric nightclub, the Gate of Horn in Chicago. A force of nature named Dawn Greening opened her Oak Park home as a sanctuary for gathering, and Old Town School was “just a gleam in Win Stracke’s eye.” The night the School opened its doors, Ted Johnson was there to teach.

Ted: On the radio, we were hearing people like the Weavers and Burl Ives, and Josh White, and Al Grossman opened the Gate of Horn, a folk club downtown. One of the musicians that sang there was this character named Frank Hamilton, who turned out to be kind of a genius.

Marcia: Frank Hamilton was here to play at the Gate of Horn but they didn’t pay very much. It was kind of a pass the hat operation. He was living with Dawn and Nate Greening, and she hooked him up with some students in her home.

Ted: Frank had just come in from Los Angeles where he had been exposed to Bess Hawes, who was John Lomax’s daughter, and different approaches of teaching people to play and get together for social music. Dawn told him, “You can teach at my house,” so naturally I showed up there and so did Win Stracke! Win Stracke had a magnificent voice but he figured he’d take some guitar lessons, too. And I still remember sitting in Dawn’s house and Frank was teaching about ten or fifteen of us, and Win Stracke turned and said to me, ‘I’m going to start a school around this guy.”

Dawn Greening and Frank Hamilton, with Win Stracke in the background, a few years after they founded the Old Town School (Photo courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music Resource Center & Archives)

When the folk singer Odetta invited Dawn Greening to the Gate of Horn to hear “the master of the art” Frank Hamilton in concert, she set in motion the very future of the Old Town School of Folk Music.

Dawn and Frank became friends and before long he was at the Greenings’ house teaching their family and friends how to play the guitar. $2 per lesson was modest even for the times, and yet it was enough to supplement Frank’s Gate of Horn earnings and allow him to stay in Chicago. After the Old Town School opened, Dawn Greening remained involved throughout the school’s first era. She served as registrar and helped hold the place together. As the story goes, she once bartered lessons in exchange for some much-needed electrical work. Her inspiration and dedication earned Dawn Greening a reputation as “the mother of us all,” and “the true heart of the school.”

Win Stracke was always interested in the working man. When he was young, he traveled out west, taking jobs as a coal miner, an oilfield worker, a ship engine-room attendant, and a migrant fruit picker. He made his mark as a folk singer, stage actor, and broadcast pioneer, performing on such mid-century radio and television programs as Studs’s Place, WLS National Barn Dance, and Dave Garroway. Before he became a target of the McCarthy-era blacklists, Win hosted his own TV shows for children: Animal Playtime and Time for Uncle Win. And as a guitar student in the Greenings’ living room, it was Win who saw the potential for creating the Old Town School of Folk Music.

Win Stracke, c. 1950s (Photo courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music Resource Center & Archives)

For over half the school’s lifetime, Mark Dvorak has helped thousands of beginners learn their first chords, led master classes and workshops ranging from old-time banjo picking to the legacy of the great Lead Belly, and guided countless jam sessions. As a young teacher, he sought out Win Stracke and got to know him. In his essay, “Win Stracke’s Dream,” Mark describes how Win’s indomitable spirit lives on.

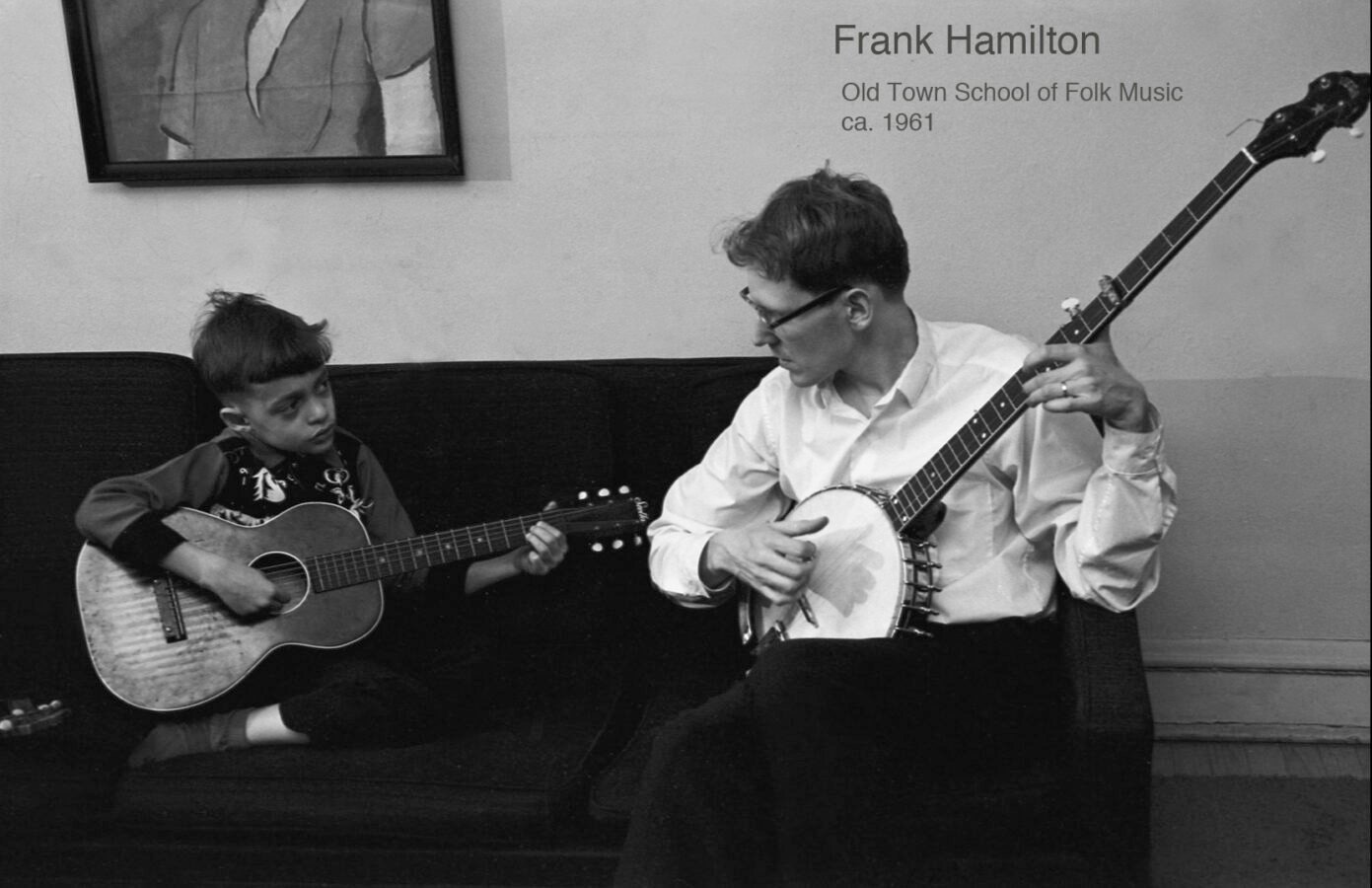

Frank Hamilton may not be a household name, but his influence can be felt across a breadth of American musical culture. When Frank arrived in Chicago in the late 1950’s, he brought with him his banjo and guitar, his strong, clear, tenor voice, and the roots of what became the Old Town School of Folk Music’s innovative, person-to-person teaching methods. He had learned these techniques in southern California from folklorist and performer Bess Lomax Hawes, and was impassioned to share the music with as many people as possible.

The man Pete Seeger once called “one of the most creative musicians in the country” served as dean of the Old Town School’s teachers from opening night until 1962, when he left to join the influential folk group the Weavers. Frank helped shape the song “We Shall Overcome,” which entered the national consciousness during the civil rights movement. One of his former students was Roger McGuinn whose band The Byrds pioneered the infusion of American folk music into rock and roll.

Frank Hamilton and a young student, c. 1961 (Photo courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music Resource Center & Archives)

Frank spent time as a studio musician of choice in Los Angeles laying down tracks for motion pictures and other projects, and eventually settled in Atlanta, Georgia. When his beloved wife Mary passed away in 2014, Frank channeled his energies into creating The Frank Hamilton School, a community music center based on the same principles as Old Town School. Through it all, Frank Hamilton has lived true to his original intention, “If I can make this world a little better by music, I want to do that.”

Opening Night at the Old Town Folklore Center, 333 W North Ave

The Old Town School of Folk Music’s first official home was in the former Immigrant State Bank Building at 333 West North Avenue in Chicago’s Old Town neighborhood. On opening night, talented musicians, including Frank Hamilton, Big Bill Broonzy, Win Stracke, George Armstrong, and Ted Johnson taught group lessons, and everyone gathered for a group jam session after class — elements which are still part of the Old Town School experience today. Despite the winter weather, the atmosphere in the Folklore Center was convivial and warm.

Frank Hamilton, George Armstrong, and Win Stracke in song (Photo: Kiko Konagamitsu, courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music Resource Center & Archives)

909 W Armitage Ave

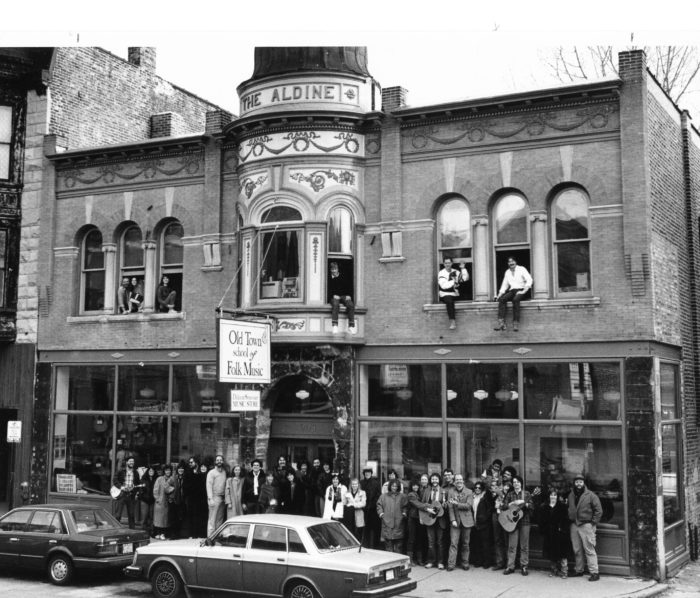

In 1968, the Old Town School of Folk Music moved to The Aldine, a ramshackle, 13,000 square-foot Romanesque Revival building at 909 West Armitage. With Ray Tate now at the helm, the school started to offer private lessons, expanded classes to every night of the week for myriad instruments, and gave numerous free faculty and student performances all over Chicago. Broonzy Hall, the large performance space on the first floor, became the spot for concerts, workshops, and the “second half,” the enduring Old Town School tradition where students of every level gather after class to play music together.

The Aldine Building, the Old Town School of Folk Music’s home at 909 W Armitage (Photo courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music Resource Center & Archives)

New Communities, New Horizons

By 1982, folk music as a national pastime had lost its glimmer. The Aldine was crumbling, enrollment had plummeted, and the Old Town School of Folk Music hovered on the brink of bankruptcy. Michael Mashkes, a bass player and finger-style guitar teacher, covered plaster cracks in the walls of his leaky basement classroom with blues tablature and postcards from his students. Physical renovations to the school and storefront weren’t the only updates needed. If the organization was to survive, it needed to find ways to adapt and diversify. And it needed to start raising money.

Conga Class, c. 1980s (Photo courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music Resource Center & Archives)

Under the stewardship of new executive director Jim Hirsch, later with director of programs Michael Miles, Old Town School entered a period of renewal and progress. This fiscal turnaround was so impressive, a reporter dubbed Jim Hirsch “the Lee Iacocca of folk music,” after the legendary American automobile executive who revitalized the Chrysler corporation. Jim didn’t start off as a folk impresario, however.

The Different Strummer music store in the 1970s. Michael Mashkes is the smiling guitar player on the left, and Jimmy Tomasello is playing with a mandolin. Also in the picture are Byron Roche, Emmy Revesz, and Betsy Redhed (Photo courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music Resource Center & Archives)

One of his most important contributions, he said, “was broadening the school’s vision to include world music. … But also I really firmly believed that if we brought diverse people together to celebrate one another’s musical tradition, it would just make the city a better place to live. That’s one of my proudest accomplishments quite frankly, you know, really creating that kind of access and showcasing the amazing music and culture that this city holds.”

A New Home for a Dollar, a Song, and the Promise to Renovate

Old Town School of Folk Music, 4544 N Lincoln Ave (Photo courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music)

The mid-1990’s found a revived Old Town School bustling with so many students that some staff members had to leave their desks early so evening classes could be held in their offices. As luck would have it, around this time the City of Chicago came looking for a suitable match for the former Hild Public Library, a 43,000 square foot structure that had stood empty for ten years or more. Arrangements were made and Old Town School bought the abandoned, art deco building for $1 plus the promise to renovate. The board embarked on its first major capital campaign to pay for the $10,200,000 gut rehab, and in 1998, Old Town School expanded northwards to 4544 North Lincoln Avenue in the Lincoln Square neighborhood.

Sliding doors open onto the performance stage in Mauer Hall (Photo: Wheeler Kearns Architects, courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music Resource Center & Archives)

The building dates from 1929 and came with two stunning examples of artwork commissioned by the Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression. These large murals by Francis Coan were restored and now hang in public areas where they can be enjoyed every day. Tony Fitzpatrick’s artwork adorns walls facing the main entrance.

A Brand New Home From the Ground Up

The Old Town School of Folk Music experienced tremendous growth after unveiling its Lincoln Square facility in 1998. Soon that building, too, was stretched to the limits of its capacity. Once again it was time to expand and for the first time in its long history, Old Town School created a brand new home from the ground up. The East Building opened in 2012, directly across the street at 4545 North Lincoln Avenue.

Old Town School of Folk Music, 4545 N Lincoln Ave (Photo courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music)

The 27,120 square foot East Building boasts three dance studios with sprung floors, sixteen classrooms engineered to accommodate percussion and electric instruments, and Szold Hall, a flexible 150-seat performance space that can be converted into a classroom, community gathering area, or social dance hall. The lobby is acoustically designed for group music-making. Various informal “jam spaces” throughout the three floors offer musicians comfortable places to gather, play, and learn from each other.

Dancers in Szold Hall at 4545 N Lincoln Ave (Photo courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music)

Photos and artifacts representing Old Town School’s past and the history of American folk music are on display everywhere. For example, portraits of blues, jazz, and country greats, framed in glass panels, line the staircase. The American illustrator R. Crumb, who created counterculture icons such as Fritz the Cat and Mr. Natural, granted Old Town School permission to reproduce his images free of charge, perhaps because he loves acoustic music from the early 20th century and played in an old-time string band called The Cheap Suit Serenaders.

May You Live to 120

Since the ’80s, Wiggleworms, an early childhood music program, has been one of the pillars of Old Town School. Many toddlers who clapped and sang in those first sessions have since enrolled their own children (Photo courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music)

As the Old Town School of Folk Music enters its seventh decade, we are reminded of the Yiddish blessing biz hundert un tsvantsig, or “May you live till 120.” Nowadays, Old Town School owns and operates three facilities in the Lincoln Square and Lincoln Park neighborhoods. The 64 classrooms, two music stores, and café brim with activity day and night. Children’s classes take place here, and at several suburban satellite locations. Performances in the 425-seat jewel box and two 150-seat concert halls feature students, teachers, and touring musicians from around the world.

Furthering the spirit of Win Stracke’s Project Upbeat from the 1970s, the Old Town School of Folk Music continues to reach out into communities all over Chicago where music and dance initiatives can be of immeasurable service. Old Town School’s expert teachers provide arts education to thousands of Chicago Public School students. Wiggleworms-in-Residence is a longstanding successful partnership with the Carole Robertson Center for Learning in the North Lawndale neighborhood. Guitars for Growth serves incarcerated students at the Cook County Juvenile Detention Center.

Musicians gather during an open house at Old Town School of Folk Music (Photo: Dan Kasberger Photo, courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music)

It’s the music and the people who make the Old Town School of Folk Music so special. The teachers, the students, and the visiting performers are all part of its collective memory and a collaborative future. Perhaps longtime teacher Bill Brickey said it best, “It’s the story of an institution growing, in part, and is indicative of the Old Town School itself. There are so many different ways to tell the Old Town School story. It’s just this amazing tapestry. It’s phenomenal that the school can touch so many lives. You know, this is what it does.

The Old Town School and WFMT

I Come For To Sing, a postwar musical revue featuring Studs Terkel, Win Stracke, Big Bill Broonzy, and Larry Lane (Photo: Stephen Deutch, courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music Resource Center & Archives)

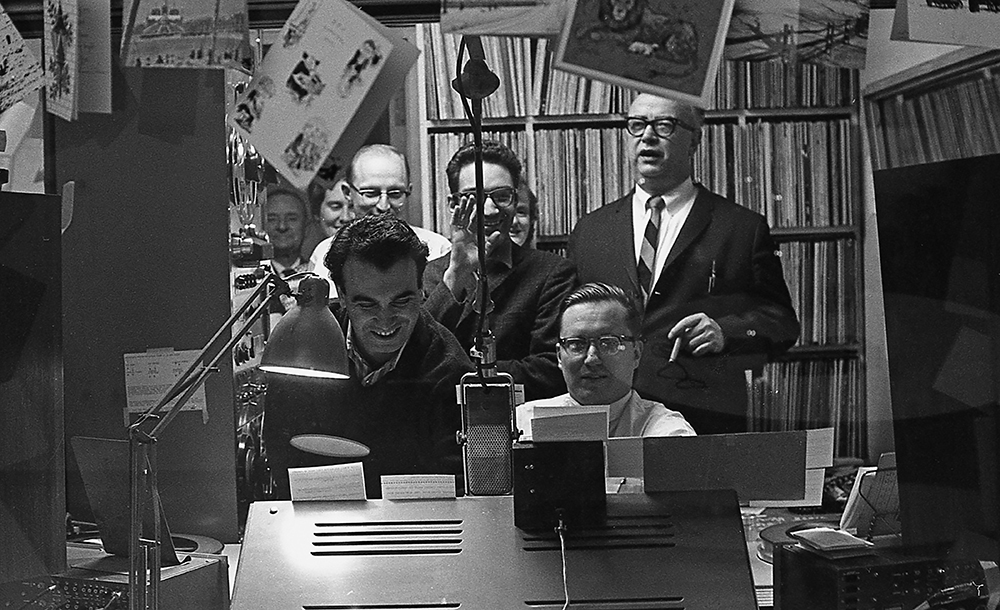

The connections between the Old Town School of Folk Music and WFMT date back to the 1930s, when Win Stracke and Studs Terkel were actors in the Chicago Repertory Group, performing socially relevant skits and songs as organizing tools for the labor movement. Later, the two friends toured with Big Bill Broonzy, Larry Lane, and others in a postwar, cross-cultural revue of poetry and songs called I Come For to Sing.

Studs Terkel joined the staff of WFMT in 1952 before the station was even a year old. He was captivated by the fledgling fine arts station that aired classical recordings along with those by Woody Guthrie. Studs spoke at opening night of Old Town School, and for the next 40 years, his radio program often featured a wide array of folk musicians, from Win Stracke and Old Town School staff to Bob Dylan and Joan Baez.

Norman Pellegrini and Ray Nordstrand, WFMT’s program director and general manager, celebrating with Win Stracke and others in WFMT’s studios in the late 1950s (Photo courtesy Old Town School of Folk Music Resource Center & Archives)

Rich Warren, longtime host of WFMT’s folk shows the Midnight Special and Folkstage, confirms that the unique and deeply rooted connection between WFMT and Old Town School goes back to the earliest days of both organizations. “Since that time,” Rich writes, “the Old Town School and WFMT resemble a binary star system orbiting around each other as the centers of the Chicago folk music scene. The Midnight Special under all of its four hosts supported and continues supporting the Old Town School because of the light and gravitas it provides Chicago’s music community. There’s no other organization in the U.S. like the Old Town School and no other relationship in folk music between a local institution and a radio station.”

“Somehow, we have tapped the strength, the beauty, the longevity of the songs we sing and channeled these qualities into a gathering place we call the Old Town School of Folk Music.”

— Win Stracke