The Martin Theater at Ravinia

I am once again climbing the same dark and creaky staircase in the recesses of Ravinia’s otherwise beautiful Prairie style Martin Theater. At the top of the second floor landing and down a long corridor strewn with cables and miscellaneous junk, I reach my destination. It's an old dressing room, now converted into a recording and broadcast booth, with microphones, mixing equipment, a laptop, a vintage 1950’s five inch black and white television monitor, and even a reel to reel tape recorder.

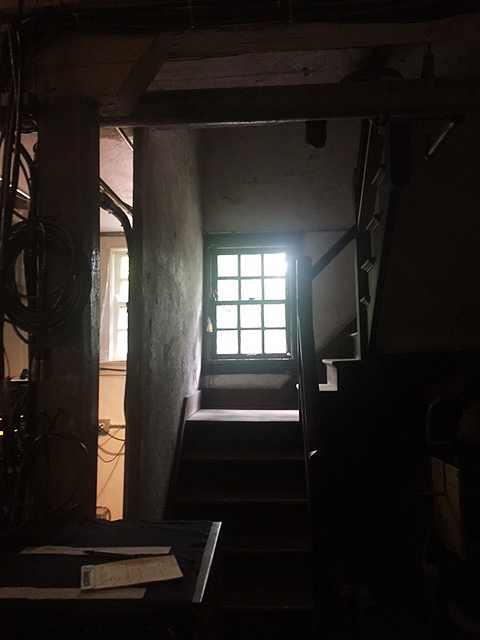

The staircase leading up to the broadcast booth in the Martin Theater

I've been making this trek for more than twenty years, usually to host a chamber music broadcast or to interview a touring musician. But today I'm interviewing my partner in crime, the Tonmeister for every one of those programs, Hudson Fair. It's unusual for a sound engineer to hold on to a gig for so long but he clearly loves it and, as you can hear any Monday night from July to October on WFMT, he does it very well.

After all these years I decided to look into just why our shows sound so good. Is it the equipment, the hall, the performers, or the man who considers all these elements and more when doing his recording? It's mostly the man, of course, using his sensibility, experience and maybe some magic, to create something resembling the actual performance.

Hudson has a philosophy in approaching this work. He maintains you can never accurately recreate the precise feeling of being a part of the audience at a live performance. What you can do is create a believable illusion using available tools. Hudson has methodically kept notes for every recording session he's ever done, reminding himself of how specific microphones, their placement, their combination with other gizmos (with and without tubes) in specific halls have affected his pickup. He can then use his equipment much as a painter uses his brushes and pallet to refine the sound. An essential part of the process is the rehearsal. That’s when he experiments with various mics, their placement, and the mix.

Hudson Fair recording in the Martin Theater's broadcast booth

And the rehearsal serves another important purpose. It's when he can get to know the artists. That rapport may make the difference between having a program go to air and frantically looking for something to fill our time slot. An artist puts his work before the public day after day. For the touring musician the circumstances are in constant flux. How reassuring it is to know there's someone listening with great care and whose opinion can be trusted. Hudson has tried to cultivate these relationships over time.

He cites the example of a very famous German baritone who’s a notorious perfectionist. After his very first appearance at Ravinia, he was initially reluctant to allow the broadcast of Hudson’s recording. Hudson’s willingness to re-record a few passages put the singer at ease and salvaged the program. When this gentleman returned in a subsequent season, Hudson forcefully reminded him of the previous success and secured a less tentative approval.

I ask Hudson if any particular recording event stands out for him in those twenty or so years. It turns out there are many, but one hot and humid night comes to mind quickly. And as he relates this story it's clear that he still doesn't fully understand what happened.

The occasion was an August 2004 recital by the great mezzo-soprano Lorraine Hunt Lieberson. Her collaborative pianist was Peter Serkin. At this point no one knew of her terminal illness. Their performance was luminous! As annotator George Gelles wrote, the subject of their program was “the gamut of love”. Hudson was up in the recording booth greatly appreciating what he was hearing, but becoming increasingly affected by the oppressively muggy night. (Our little corner of the Martin Theater is untouched by air conditioning.) Then it was all too much. He slumped over his mixing board in what he described as some kind of “stupor.” But somehow in this state he continued to work - moving his faders in reaction to what he only subconsciously heard. The next day when he reviewed what he had done, he was amazed! He managed to capture the emotional intensity and beauty which emanated from the stage.

In 2007, Harmonia Mundi released the recording commercially. Hudson won a Grammy, and an even more profound appreciation for the art of illusion, or maybe… magic!