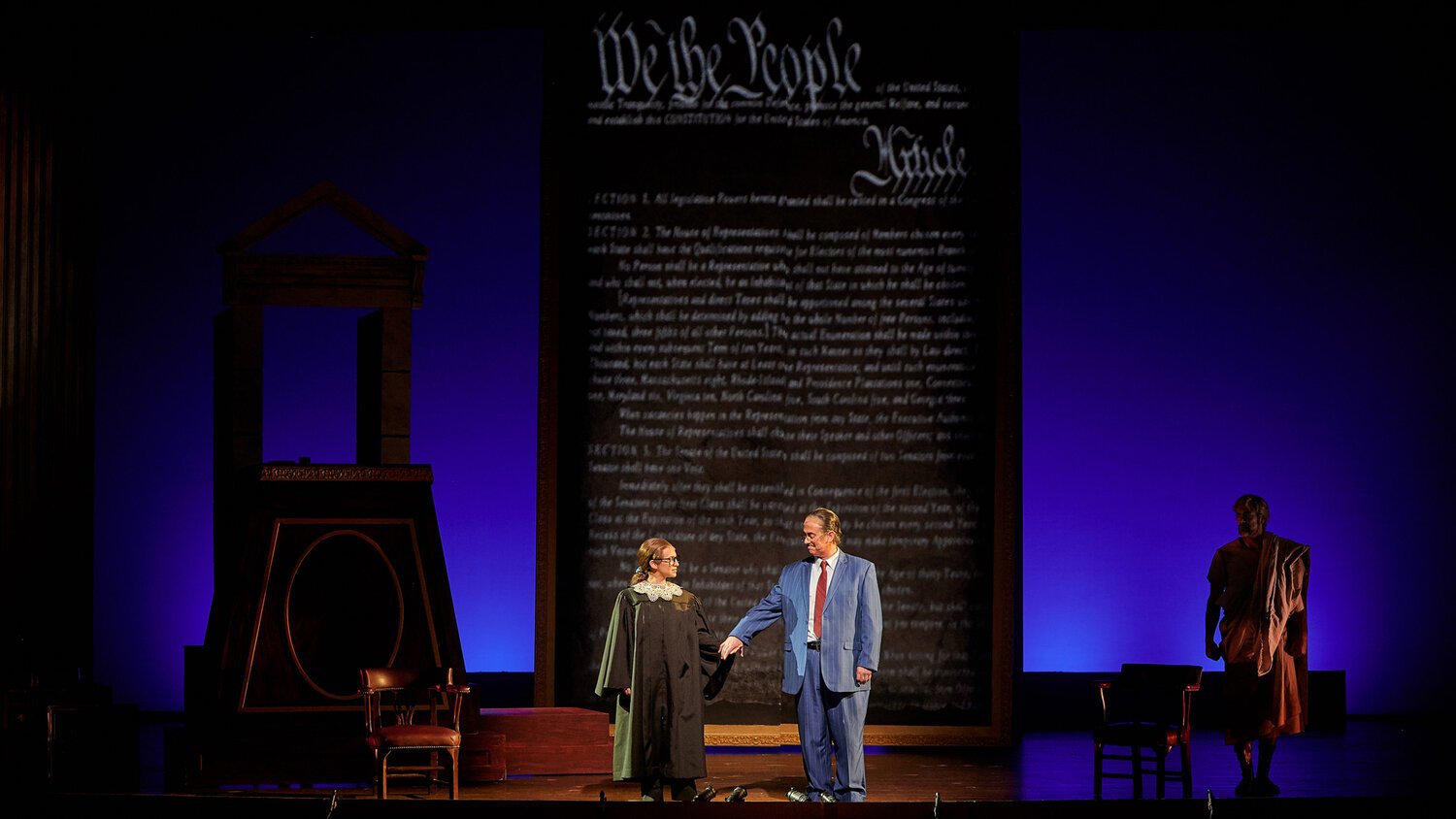

Jennifer Zetlan as Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Brian Cheney as Justice Antonin Scalia (Photo: Joe del Tufo, Moonloop Photography)

The worlds of the opera house and courthouse collide in Derrick Wang’s opera Scalia/Ginsburg, a comedy about friendship in a divided world. The work is inspired by the real-life words and relationship of two ideologically different US Supreme Court Justices: Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Even though these two disagreed on many things, what united them was humor and a love for opera. But what would happen if the two unlikely friends had to appear before a higher power?

The opera begins in the Supreme Court Building when Justice Scalia is confronted by the Commentator, a supernatural being who seals the room, stating “No man shall enter.” Scalia is forced to defend his approach to the law and may escape only by passing three trials: an inquisition, a trial of silence, and a mystery (not unlike Mozart’s The Magic Flute). But since Justice Ginsburg is a woman, she is able to break into the courtroom to aid her friend, insisting on taking the trials alongside him.

Derrick Wang, who is a former practicing attorney, with music degrees from Harvard and Yale, was both the composer and librettist of the opera, which features actual lines from the justices’ opinions and speeches. The music has nods to Handel, Mozart, and Puccini as a sort of musical precedent. Wang actually presented excerpts of the opera to both justices at the Supreme Court in 2013. WFMT spoke to Wang about the creation of his opera, how he was able to integrate legalese into his libretto, and the challenges of putting these larger than life figures into his work. You can hear the opera as part of a double bill from OperaDelaware, which will air on WFMT on November 7 at 12:00 pm.

WFMT: Where did the idea for this opera come from?

Derrick Wang: The idea for Scalia/Ginsburg came from my experience of being not only a composer and dramatist, but also a law student inspired by the dueling opinions of US Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia. When I was studying constitutional law, I was reading case after case after Supreme Court case when I came upon three magic words: Scalia, J., Dissenting. Every time I read a Scalia dissent, I would hear music in my head, a rage aria, a type of song made famous in Italian operas of the 1700s, about the Constitution. And like a dissent by Justice Scalia, a rage aria is passionate and virtuosic and rooted in certain principles of the 18th century.

Then when I read the contrasting counterpoint from his colleague and fellow opera aficionado Justice Ginsburg, I realized the unlikely friendship between these two justices could itself be the basis for an opera. So, I put my music degrees to work, combined them with a law degree from the University of Maryland, and here we are.

Composer Derrick Wang

WFMT: What makes the US Supreme Court a good setting for an opera?

Wang: It’s funny that you ask this question because nearly a decade ago, when I was first inspired to write this opera, the Supreme Court was not the kind of topic that you would write an opera about. For example, there weren’t as many Supreme Court Justice-themed books or movies or blogs or memes or T-shirts or tattoos as there are now. So, it wasn’t really about writing something ripped from the headlines. Instead, it was more about the fact that, as the saying goes, conflict is the essence of drama. And certainly, there is some conflict between the differing opinions of different Supreme Court justices. What’s more, the stakes are high because the Supreme Court clarifies and interprets the law of the land.

And yet this conflict is relatable to all of us. Because, like the justices, we all have people in our lives who disagree with us. And yet we all need to find a way to coexist.

WFMT: What were the challenges of using the legalese in the libretto? How did your studies with the law help you?

Wang: When I started writing Scalia/Ginsburg, one of my goals was to create a musical and theatrical experience that, true to its title characters, could bring people of different backgrounds and viewpoints together through opera. To do that, I knew that what I wrote would need to explore contrasting ideas deeply yet harmoniously and with a light touch, rather like a soufflé layer cake, albeit one that can serve hundreds of people at once.

And one of the main challenges in creating a work like Scalia/Ginsburg was to make the complexity of constitutional law understandable to a wider audience. And the more I studied law, the more I realized that law and opera have something in common: they both have strong traditions and precedents. So, I developed a technique I like to call “operatic precedent,” I created the music in the style of a Supreme Court opinion. Just as a Supreme Court opinion must quote, paraphrase, or otherwise be based on the precedent set by previous court decisions, the score I composed is a mosaic of allusions and references to influential musical styles of the past.

As for the words, even though I wanted almost every statement sung in the opera to be sourced to something the justices said or wrote, I decided to write my libretto using more everyday language and then slip in legal references like Easter eggs. For example, there’s a verse that goes as follows, “The justices grew wise and felt paternalism was just a con.” Now, the surface meaning is all we need to follow the story. But if you’re a lawyer, it doesn’t hurt to know that Wiesenfeld and Kahn are the names of two cases that Ruth Bader Ginsburg litigated before the Supreme Court.

(Photo: Joe del Tufo, Moonloop Photography)

WFMT: What kind of reaction have you gotten from your opera? Is there a message you hope your audience walks away with?

Wang: I’ve been delighted to hear from audience members who came for one layer of the cake, as it were, and left with the greater appreciation for the other flavors, whether it’s a lawyer who now wants to learn more about opera or an operagoer who now wants to learn more about the Supreme Court, or, perhaps most importantly, any audience member who enjoyed the comedy and also recognizes that friendship can indeed transcend political differences, I’m grateful that audiences share my interest in learning from the theme of Justice Ginsburg and Justice Scalia’s friendship.

Although I wouldn’t necessarily say that the primary purpose of art is to promote a message. I was inspired when writing this opera to create a motto that became the central duet of Scalia/Ginsburg: “We are different, we are one.” And I hope that just as Justices Ginsburg and Scalia could fiercely disagree while remaining close friends, we the people, who differ in so many ways, can find a way to understanding each other.

WFMT: What are you working on now, and are law and music still a part of it?

Wang: Being in both the musical and legal worlds has shown me how different disciplines, fields, and groups of people can connect to each other in unexpected ways. Because of these unprecedented times, my current project is neither an opera nor a legal document. Instead, it’s a newsletter called Arsapio.

Arsapio is a newsletter helping artists and businesses work together. Breaking down the myths around art and business, exploring what they have in common, and providing suggestions for putting this knowledge to work. Launching in November 2020, the first series of articles explores the unsung superpowers of classical musicians in the virtual workplace.

You can listen to Scalia/Ginsburg as the second part of a double bill from OperaDelaware paired with Gilbert and Sullivan’s’ courtroom farce Trial by Jury on November 7 at 12pm CST on 98.7 WFMT in Chicago or you can stream it live here: www.wfmt.com/listen. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.