Instruments being restored for the Violins of Hope project (Photo courtesy: JCC Chicago)

Instruments carry a life of their own, reflects James A. Grymes. “There is a spirituality to the instruments… violinists tell me that they can actually feel the technique of a previous violinist. They immediately form a connection with those who played the instrument before them.”

Grymes, a professor of musicology at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, began his career researching the life and career of Ernst von Dohnányi. The Hungarian composer spent the last decade of his life teaching at Florida State University — where Grymes completed his doctoral degree — after fleeing his native country to evade the Soviets and Nazis. “He never recovered politically or professionally,” Grymes concludes.

James A. Grymes

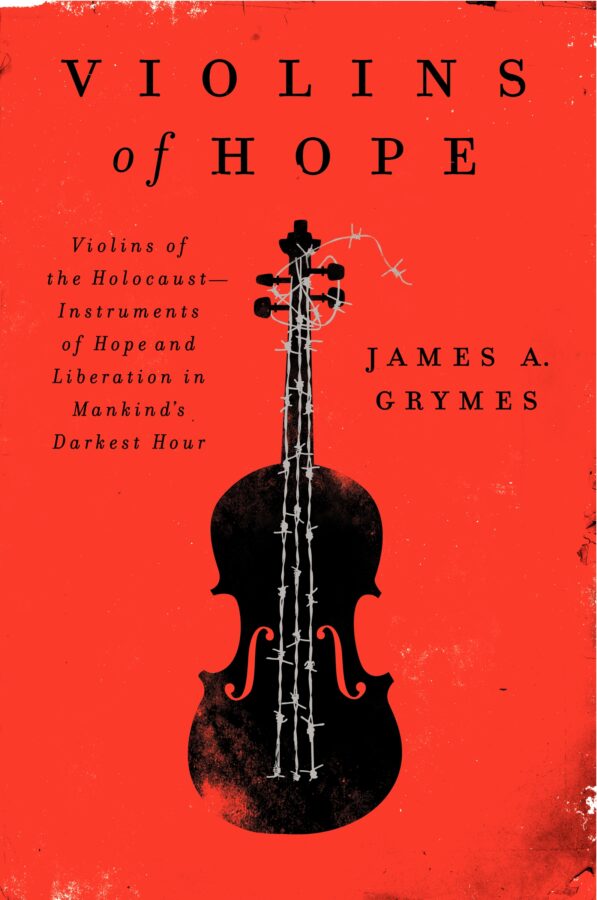

This fascination with migrations and their musical fallouts led Grymes to a new project. His 2014 book Violins of Hope recounts stories of the Holocaust through the lens of music. Grymes tracks violins owned by artists and individuals who were victimized, threatened, or killed by the Third Reich and chronicles their rejuvenation by an artisan violin maker — Amnon Weinstein — and his family. In their ongoing work, the Weinsteins preserve and restore these instruments… and their owners’ stories.

The Violins of Hope project visits Chicago in May and June in a lineup of events presented by the Jewish Community Centers of Chicago. Anchored by performances on revived instruments including at the Elgin Symphony Orchestra (May 20), Chamber Music on the Fox (May 21), and the Northbrook Symphony (both June 4), the Chicago area tour also features student engagement programs, public lectures, screenings and exhibits. We spoke with Grymes, who will be presenting these stories in lectures throughout the Chicago area events.

WFMT: Let’s start with the instruments. How did they escape the Holocaust, and how do they come to find the Weinstein family?

James A. Grymes: Most of the world-class musicians were able to get out. There were jobs for them in American orchestras, part of the intellectual migration that suddenly saw Albert Einstein in Princeton and Arnold Schoenberg in Los Angeles. So those left behind were maybe the next generation, who didn’t have the best instruments yet. Or they were amateurs, or even Klezmer musicians. As such, most of their instruments were not concert quality; many were mass-produced and made very cheaply.

One example that I delved into is the Davidovitz brothers. Their father bought a violin right after the war from an impoverished Auschwitz survivor. Not because of its historical value, but simply because he hoped his sons would learn to play the violin. The boys just never took to it, but it stayed in their house for decades. “What are we going to do with this violin?” The thing was in Auschwitz, you’re not just going to put it on eBay. They ended up donating it to the project.

Amnon Weinstein and his son, Avshi, are both world-class violin makers. Theirs is a confluence of these stories. As Jewish people and Israelis, the specter of the Holocaust has loomed large in their psyches. And they, as with so many others, lost so many family members.

They go into the instruments, take them apart, and rebuild them. The body of the instrument is left intact, but there’s a huge amount of work that goes into bringing them up to concert quality inside the instrument.

Amnon Weinstein (Photo: Miki Koren)

WFMT: What’s the process like for the artists playing the instruments?

Grymes: It’s an interesting sort of ceremony that happens. The violins are put out and the artists play and compare the instruments. There’s some sort of mechanical considerations: what feels most like my normal instrument? But there’s also this embodiment, with the artists asking, “What does this instrument say to me?” You can see them picking up instruments, playing for a few notes, then they pick up another one. Eventually, they all end up with the one they want.

I’m not a violinist. I always ask, “Don’t you need more time?” They say, “No, give me a couple of hours to practice and acclimate myself. I’ll be fine.”

For the Elgin Symphony Orchestra performance, there will be two dozen instruments from the Violins of Hope being played by members of the orchestra. This is a chance to see the instruments and hear them come alive again. That’s the heart of the Violins of Hope project. They’ll be on display throughout the Chicago area, and they are beautiful museum pieces. But at the heart of this project is that they are being performed on again.

WFMT: Why do music — and these instruments — make such a compelling way to explore these histories?

Grymes: There is something so innate about musicmaking. It is a quintessentially human activity.

Through my studies and discussions with survivors and their ancestors, what I’ve learned is that music can maintain community and uphold humanity, even in the darkest of times.

At someplace like Auschwitz, which was heavily monitored with no time for anything beyond working or sleeping, they still find moments to sing to each other, sometimes in exchange for a little bit of bread. So this person who’s slowly being starved and worked to death, they’re willing to give up a little bit of their food to experience music.

With every passing year, there are unfortunately fewer human Holocaust survivors among us to tell their stories. These violins, as a different type of survivor, can go on for generations.

That’s something I think is special about this project, and it’s something I remind my students as often as possible. The Holocaust is not a single story of six million deaths. It’s six million different stories, many of which we will never know. But we can get to know a handful of the stories through these violins of hope.

For more information on Chicago-area events for the Violins of Hope, visit jccchicago.org/violins-of-hope. For information on James A. Grymes, visit jamesagrymes.com. For the Elgin Symphony Orchestra performance, visit elginsymphony.org. For the Chamber Music on the Fox performance, visit chambermusiconthefox.org. For the Northbrook Symphony performance, visit northbrooksymphony.org.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.