The Old Plantation (Slaves Dancing on a South Carolina Plantation), ca. 1785-1795. watercolor on paper, attributed to John Rose. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, Williamsburg, Virginia, USA.

African-American spirituals are not just a cornerstone of the American choral tradition, they have impacted countless genres of music heard everywhere from saloons to symphony halls. Antonín Dvořák‘s Symphony No. 9 in E minor, “From the New World,” borrows heavily from African-American musical traditions and spirituals in particular. The composer once said:

“I am convinced that the future music of this country must be founded on what are called Negro melodies. These can be the foundation of a serious and original school of composition, to be developed in the United States. These beautiful and varied themes are the product of the soil. They are the folk songs of America and your composers must turn to them.” — Antonín Dvořák

But, what’s the history behind African-American spirituals? How did they become so popular that even Dvořák adored them? And how have they changed music forever?

Signifyin’ Through Spirituals

Difficult and dark themes are coded in Dvořák’s words that African-American music is the “product of the soil.” Spirituals were born when Africans were forced to work American soil as slaves. Taken from their native land and bound by shackles, African slaves blended their native musical traditions with European ones. Music and dance provided an outlet for slaves to express their sorrow, though often their cries of pain sounded quite the opposite to slave owners. Frederick Douglass, the former slave who became an important orator, author, and abolitionist observed:

“I have often been utterly astonished, since I came to the north to find persons who could speak of the singing, among slaves, as evidence of their contentment and happiness. It is impossible to conceive of a greater mistake. Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy.” — Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass wrote at length about how slave songs were a way to signify: a kind of double-speak that exploits the difference between denotative and connotative meanings of words, especially of signs that have special significance to a particular subculture. In fact, Douglass himself confessed:

“I did not, when a slave, understand the deep meanings of those rude, and apparently incoherent songs. I was myself within the circle, so that I neither saw or heard as those without might see and hear. They told a tale which was then altogether beyond my feeble comprehension; they were tones, loud, long and deep, breathing the prayer and complaint of souls boiling over with the bitterest anguish. Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains.” — Frederick Douglass

Of particular importance in the signs and signification in spirituals are references to the bondage of the Hebrews in the Old Testament of the Bible. Thus, slaves could communicate Christian values to those “outside the circle” that were imposed upon them by slave owners. But, at the same time, they could communicate hidden meanings “inside the circle” about their own bondage.

The Great American Tradition That Almost Wasn’t

The Jubilee Singers

In the years following the end of the Civil War and the emancipation of slaves, African-American musical traditions were becoming increasingly known “outside the circle” in the United States. But, it’s almost by accident that the great musical tradition of African-American spirituals became known to the world at large.

In 1871, the historically black college Fisk University was facing financial failure, and the University’s music director, George L. White, assembled a touring chorus composed of members of the student body to raise revenue. White, a white missionary from the North, traveled with two quartets and a pianist along the Underground Railroad giving concerts of patriotic songs, hymns, and popular songs of the day.

Originally, the concerts were not a success. Though faced with dire financial circumstances of their own, the touring choir selflessly donated their profits from one concert in Cincinnati entirely to support victims of the Great Chicago Fire in October 1871, leaving them pinching for pennies and on the verge of turning back for home.

White, however, decided that their concerts would be more successful if the musicians changed their programs to feature African-American spirituals, and established a name to capture the imagination of their audience. They called themselves the Fisk Jubilee Singers, with “jubilee” an allusion to the book of Leviticus; the “year of Jubilee” would be when all slaves were set free. Since most of the student musicians of the Jubilee Singers were the children of newly freed slaves themselves, the name could not have been more fitting. Hear one of the earliest recordings of the Singers.

At first, the musicians were reluctant to perform spirituals in public since they were grim reminders of our nation’s troubled past. However, the group’s a cappella arrangements of traditional spirituals arranged for soprano, alto, tenor, and bass incited intense interest in African-American music. A year after forming, the Jubilee Singers printed a collection of the music they performed, which was so popular it was reprinted in an expanded edition the same year. Mark Twain’s firsthand account of the group’s original performances captures the energy and excitement surrounding them:

“Then rose and swelled out… one of those rich chords the secret of whose make only the Jubilees possess, and a spell fell upon that house. It was fine to see the faces light up with the pleased wonder and surprise of it…. Arduous and painstaking cultivation has not diminished or artificialized their music, but on the contrary – to my surprise – has mightily reinforced its eloquence and beauty. Away back in the beginning – to my mind – their music made all other vocal music cheap; and that early notion is emphasized now. It is utterly beautiful, to me; and it moves me infinitely more than any other music can.” — Mark Twain (1897)

Soon, word about the Singers traveled across the pond, and eventually, so did the Singers themselves. On one European tour, the Jubilee Singers performed before Queen Victoria. She exclaimed that their voices were so beautiful they must be from “Music City,” giving birth to Nashville’s epithet “Music City, USA.” On a subsequent European tour, the group earned $150,000, which provided funding to construct the first permanent building for Fisk University, Fisk Hall, which still stands in Nashville.

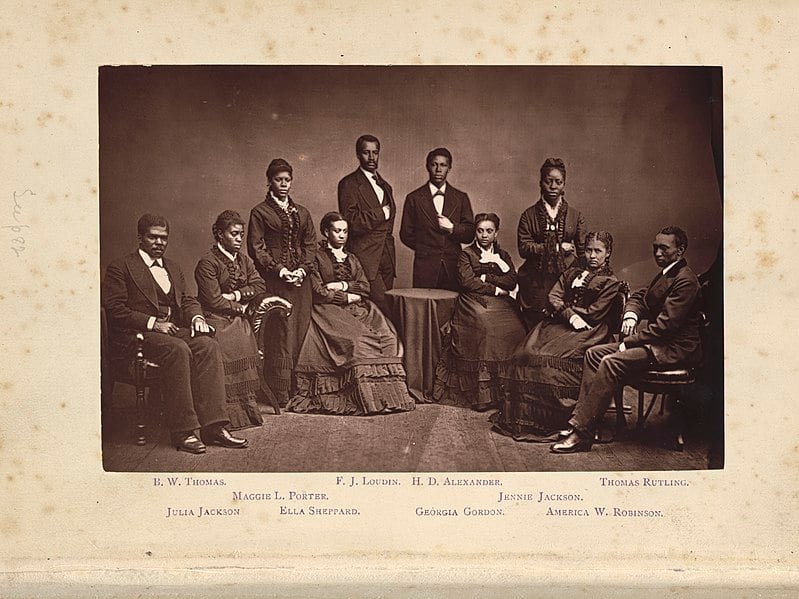

A portrait of the Fisk Jubilee Singers’ performance before Queen Victoria painted in 1873 by Edmund Havel, the queen’s court painter. Left to right (men): Benjamin Holmes, Isaac Dickerson, Thomas Rutling, Edmund Watkins; left to right (women): Mabel Lewis, Minnie Tate, Ella Sheppard, Jennie Jackson, Julia Jackson, Maggie Porter, Georgia Gordon.

The Legacy of the Fisk Jubilee Singers

The Fisk Jubilee Singers are still singing today, carrying on the great tradition of sharing African-African spirituals that started almost 150 years ago. But, the impact of the Jubilee Singers on the world of music is immeasurable. Though some African-American musical traditions were popular before the Jubilee Singers formed, they brought the sounds of suffering, sublimated through song, to the world.

In fact, there are many songs that were originally sung by slaves that have become so much a part of our culture that we might now be unaware of their original context. For example, “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore” was popularized among white audiences by Pete Seeger. But, the song was originally published in 1867 as Slave Songs of the United States, the first collection of its kind.

While the original context of some slave songs has been obscured over time, composers and performers still explore the expressive power of spirituals. In the clip below, soprano superstar Jessye Norman has recorded her own version of “Lord, I Couldn’t Hear No Body Pray,” a traditional spiritual.

We can compare Norman’s version to one of the earliest recordings of this piece, which is by the Fisk Jubilee Singers themselves, to hear how the tradition of African American spirituals goes on but has evolved: