Sono Osato (Photo: sono-osato, CC BY-SA)

“I think I am one of the few American dancers who ever saw the Diaghilev ballet at the peak of its glory,” Sono Osato begins her autobiography Distant Dances. At the ripe age of 14, Osato became the first American dancer to join the Ballet Russes de Monte-Carlo, derived from Diaghilev’s famous Ballets Russes.

With the company, she toured the world dancing alongside the Bronislava Nijinska, Michel Fokine, and Leonide Massine. She performed in early revivals of famous works like Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, and Stravinsky’s Petrushka.

Osato, now 96, has worked with everyone from Balanchine to Leonard Bernstein, Jerome Robbins to Frank Sinatra in her long career. But, her journey was not without its difficulties.

Her family life was complicated. Life on the road during the Great Depression was demanding. She saw the rise of the Third Reich while living off rations in Berlin, Germany, and even performed for Hitler.

Thodos Dance Chicago is exploring Sono Osato’s long and full life in a new dance work called Sono’s Journey, which has its world premiere in Chicago on Saturday, January 9, 2016. WFMT spoke with Osato herself about her incredible journey.

WFMT: In your autobiography, you go into a lot of detail about your personal life, discussing everything from family problems to having an abortion as a teenager in the 1930s.

Sono Osato: Dancers in shows do not have very much of a private life. We didn’t talk about our private lives because it wasn’t very important. I tried to bring in aspects of my personal life in my autobiography so that people might have a different feeling about dancers. Whenever people talk about dancers, I feel there’s a great deal of prejudice about their dumbness. That annoyed me. I said once, “How intelligent do you have to be memorize – overnight – as much as you can to a Stravinsky score when you’re not a musician?” I can’t read one note of music. It doesn’t mean I can’t dance to Stravinsky. I’ve danced to much Stravinsky in my life.

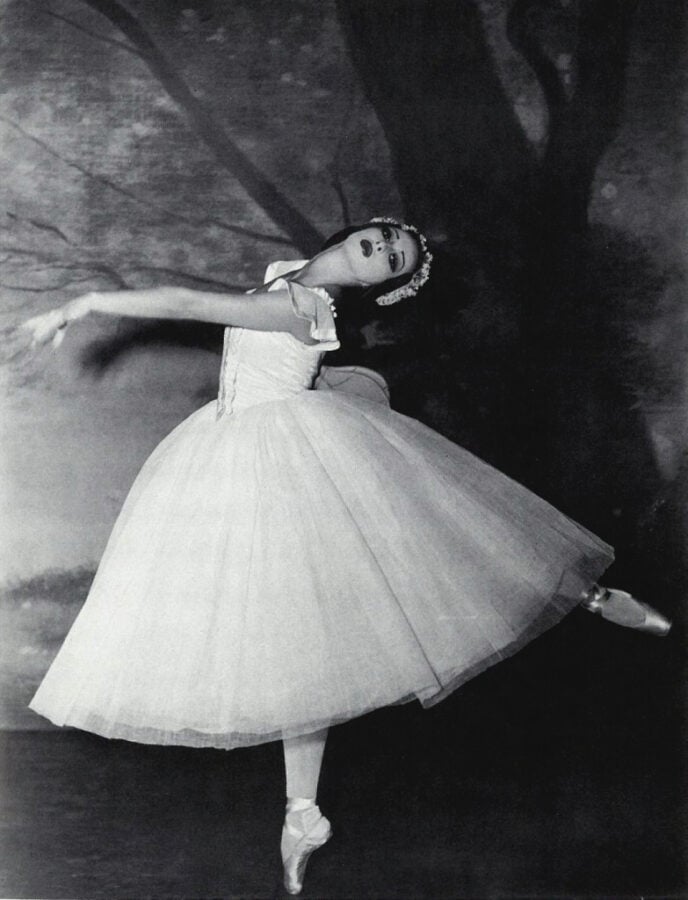

“In 1939 I was so poor that you can see where I had to patch my tights at the heel.” – Sono Osato (from Distance Dances, 1980; Photo: sono-osato, CC BY-SA)

WFMT: On your very first day working with the Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo you were thrown into rehearsals for Swan Lake.

Osato: There was no time. There was no time to do anything. There was no time to translate properly. They spoke mainly Russian and French. Thank God I spoke French fluently. It took a lot of patience because it took a long time to translate from Russian to French to English. That was very frustrating to everybody – they couldn’t communicate properly. What they would do is do the step over and over again until they got it right. And when they got it right, we all yelled, “That’s right!” Rehearsals were fraught with lots of language problems. People would think, “Wait, let me think of it in French. No, I won’t say it in French.” There was a lot of that going on, people saying, “No, I won’t discuss this now,” because it would take too long. But in a way, it was great fun.

WFMT: Can you tell us more about working with Fokine and Massine?

Osato: Personally, if I could only work with one of them, I would take working with Fokine. He was very available as a person. He was very believable as a choreographer, and of course, he was a wonderful choreographer. But I’ve always loved every dance I’ve seen. I always think, how did that man or woman take all of those people, mix them up, and then figure out what to do with each group. I was always mystified. It was the most inventive thing I had ever seen. I never imagined there were so many talented choreographers.

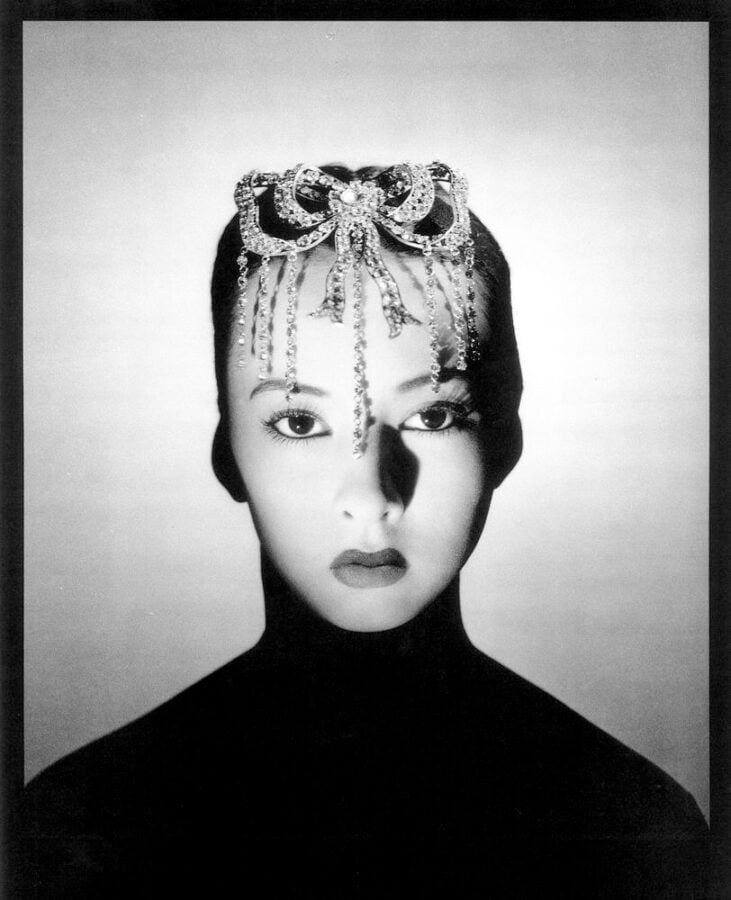

Sono Osato photographed by George Platt Lynes (Photo: sono-osato, CC BY-SA)

WFMT: What advice do you have for dancers today?

Osato: It’s very good for dancers to know classical ballet – it’s very, very important. It adds a great deal to their talent to be able to dance in the classical mode. If they can’t, it’s something they can learn. They can certainly adapt themselves to perform works today while learning what people did yesterday. Classical ballet is wonderful when it is danced properly – it’s not stuffy at all. It’s quite hard to be a classical ballet dancer today because everything is so modern. But that method will endure for some time, it’s still valid. It’s valid from a health point of view, from a feet protection point of view, and from a style point of view.

The style is very difficult, but sometimes it looks silly because a dancer will enunciate every step of the way and that gets boring. When you announce what the step is going to be, and when you show in a way that you break it down, you won’t even understand what you’re trying to show people, and the audience won’t understand the bigger picture.

Osato dancing in “The Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun” (left image, pictured center) and “Scheherazade” in 1937 (right image)

It’s a very fascinating art. It’s very special. Some people are wonderful at it. Some people can do it, but they’re not wonderful at it, so they shouldn’t do it. It also requires a special kind of charm which I don’t see today. Everything has become very bold. Smiles are very bold. Eyes are very bold. Everything. That spoils the classical way of doing things.

In those days, people didn’t show their emotions so much, even when people were on the stage. Well, Sarah Bernhardt did, she showed her emotions plenty. But for dancers, they felt it was not appropriate because the dance expressed what the choreographer meant, and that’s the most important thing – to follow the choreographer’s desire. Otherwise, there’d be no style in classical ballet.

Today, everybody wants to have their own voice in this new art. And they’re right to want that if they have something to contribute. America has much more to contribute than she knows. I mean there are lots of movements that have down from the past in America that people don’t consider art. And in America we have a brand new branch of dancing and it has endless possibilities with people with imagination. I hope that it grows.

WFMT: What do you think makes for an exceptionally talented dancer?

Osato: Men should not be too tall nor too heavy. Same for women, but women need a longer neck for classical dancing. Classical dancing with short necks hardly shows at all the important movements. The neck is as important as the feet. It’s important for the dancer to have the right body. You can’t have a dancer with a terrific jump but who doesn’t have the right body. A short dancer often has great jumps, but can’t do other movements well. Then, someone with long legs can’t jump as well, even if they have other advantages. So the legs can’t be too long. I see some modern dancers with long legs who do big leaps and it looks so difficult to me, I can’t understand how they do that. A certain kind of build is needed to make this kind of dancing really wonderful.

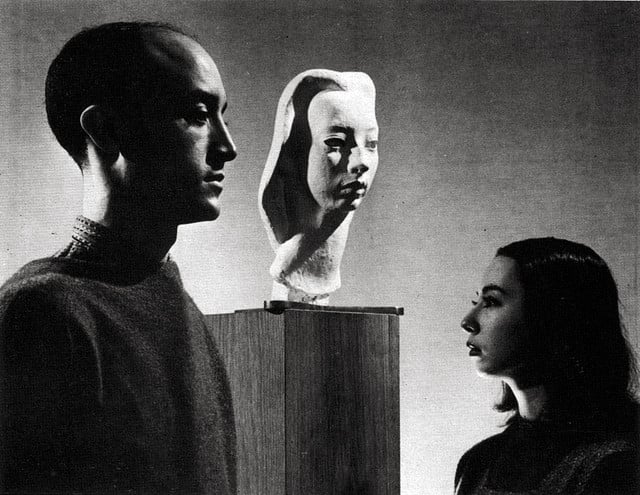

Isamu Nouchi and Sono Osato pictured with his bust of her (Photo: sono-osato, CC BY-SA)

WFMT: The artist Isamu Noguchi created an incredible sculpture of you, how did you meet him?

Osato: My family lived in Chicago for many years, and my father, who was pure Japanese, met Noguchi through the Art Institute of Chicago. Noguchi was all over the place at the time, and he was certainly better known in other parts of the world than he was in America.

During one of Noguchi’s Chicago visits, my father and mother met him at some reception or something and they became as friendly as new friends can become in a single night. And after that, he would always visit my parents when he was in Chicago which was very nice.

He had seen Martha Graham – I’m not sure how their friendship began – but they got together and he designed sets and costumes for her dances, so he had an interest in dance.

WFMT: When did he decide that he wanted to sculpt you?

Osato: I’m not sure when he decided he wanted me to pose for him. I knew he was one of the few Japanese-Americans who was in the field at the time.

I got to know him very briefly, but very well. He didn’t stay in one city for a long time. He was finding his way in the art world, and I think he wanted to find it his way. He wanted to meet everyone. What they looked like. How they spoke. What they thought.

But I posed for him at least five times, and he was the fastest artist I ever posed for. I could quickly recognize myself in the sculpture and I thought, “That’s really amazing!” And he said, “I didn’t look especially at the face, I looked especially at the body in order to translate your movement.” I was always fascinated to see if an artist could translate a human image into painting or sculpture or drawing, and he sure did. I was very moved to see how accurately he did that.

He was quite a nervous man. He was not still. It was hard for him to sit down, and he was always in action. He was always going somewhere, and that impressed me – he had tremendous energy. He went far, and he was doing well in his career. He was indeed very fascinating looking and handsome.

Bust of Sono Osato by Isamu Noguchi (Photo: sono-osato, CC BY-SA)

WFMT: Well, you’re very beautiful yourself!

Osato: When I was posing for him he said, “I think we ought to get married.” I said, “I don’t want to marry anyone ever, EVER in my life!” My parents’ marriage was unfortunately not the happy thing I hoped it would be. I was very sad they didn’t love each other.

So there was the end of that fantasy. But I still have his bust that he made of me in clay and in bronze.

I found he had also proposed to my sister, Teru, who is fourteen months younger than me. She was going to Bennington College at the time. She turned him down and he was very disappointed. It’s very amusing that he did that to my sister and me.

Noguchi, who is also half-Japanese and half-American, thought it would be nice to have two people of the exact same bloodline together. He said, “We could create a new race.” And I said, “No, sorry. I’m never going to marry anyone, and I certainly wouldn’t want to marry anyone who wants to start a new race.”

People need to accept us as people, not because we’re of a particular race. It’s difficult for any racial minority in this country. There’s so much prejudice, and that’s not what we’re supposed to stand for.

To learn more about Sono Osato, read her autobiography, Distant Dances. To learn more about Sono’s Journey, visit the Thodos Dance Chicago website.