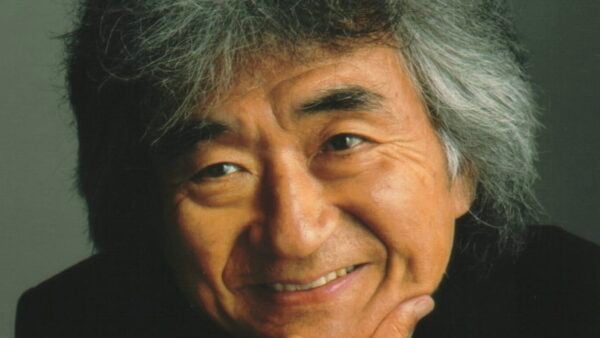

Mariss Jansons (Photo: Bayerischer Rundfunk)

Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7, titled “Leningrad,” was written during one of the most horrific sieges in history. From 1941 to 1944, Hitler’s army surrounded Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), and over one million civilians died.

Conductor Mariss Jansons, renowned for his interpretations of Shostakovich symphonies, has a particularly interesting connection to Leningrad. Jansons was born in Soviet-controlled Latvia. Later, he would go on to study at the Leningrad Conservatory and eventually conduct the Leningrad Philharmonic.

Before leading the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra in the “Leningrad” at Chicago’s Symphony Center, Jansons spoke about the power of Shostakovich’s music and how it still resonates today.

Shostakovich began Symphony No. 7 in the summer of 1941 before he evacuated to Kuibyshev. The completed symphony received its premiere in Kuibyshev on March 5, 1942.

Three men burying victims of Leningrad’s siege at the Volkovo cemetery (October 1, 1942)

Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin praised the work for its resistance to German fascism. However, Shostakovich’s criticism of Stalin permeated his music and personal life. Even though Shostakovich dedicated the symphony to the city of Leningrad, he noted that Leningrad was already being “systematically destroyed and that Hitler is merely trying to finish it off.”

“Although I was only born during the war, there were similar things Shostakovich and I experienced,” Jansons recalled. “The whole atmosphere of this symphony is not only about the war but it is also about everything that is negative and human beings struggling,” Jansons declared. “The symphony could mean this and that to someone else. Therefore, my voice is to follow the voice of Shostakovich.”

Shostakovich’s voice gave the people of Leningrad hope in August 1942. Though the majority of the musicians from the Leningrad Radio Orchestra died during the siege, conductor Karl Eliasberg, surviving musicians, and military supplements managed to perform the symphony.

Oboist Ksenia Matus, who participated in the performance, said in the documentary The War Symphonies, “Music was everything. Never mind the kasha or that we were hungry. No one could feed us, but music inspired us.”

Audience member and siege survivor Tatiana Vasilyeva, as quoted in The War Symphonies, added, “When I entered the hall, tears came to my eyes because there were many people, all elated. We listened with such emotion because we had lived for this moment. We realized this concert might be the last thing we’d do in our lives.”

Given the traumatic history of this work, how does Jansons convey this urgency to his orchestra?

“The music speaks for itself,” Jansons said emphatically. “Every musician who has feelings or a sense of fantasy can immediately feel Shostakovich’s atmosphere. That is most important.”

Jansons continued, “Perhaps it’s not directly copied from Shostakovich, but the general associations and feelings from this music are so strong. You can, of course, explain something during rehearsal, but not a big lecture. There are some moments when you should not explain anything. You can use your hands to show what you want, sometimes with your eyes.”

According to Jansons, continuing to perform and introduce Shostakovich’s music to audiences around the world is vital. “The most important thing is that the audience member feels an impact and that they have heard something very special. This symphony will last forever because the individual’s view of society, the struggle between good and bad energy, hope and depression – these ideas Shostakovich expressed will always exist, even in our world now.”

Do composers and musicians have an inherent responsibility to react to political struggles today?

“It’s not a must,” Jansons explained. “There is not a rule that a composer must write about political situations. Newspapers and television, yes, they must immediately react. But of course, if the composer wants to express their feelings, they must write and express. Music from bad times gives us positive feelings, positive energy that helps us to survive and live.”