Templo de San José, Part of the Jesuit Missions of the Chiquitos World Heritage Site. (Photo: Marcelo Claros Marzana, CC BY-SA)

When exploring the jungles of South America, perhaps one of the last things you would expect to find are centuries old scores by European composers like Scarlatti, Vivaldi, Bassani, and Hasse. But that’s exactly what Father Piotr Nawrot encountered in Jesuit Missions located in modern-day Bolivia, along with the score to an opera, San Ignacio, which receives its Midwestern premiere this Sunday at the Art Institute of Chicago as part of the Chicago Latino Music Festival.

Scholars today assumed that when the Jesuits were expelled from Spanish territories in the mid-18th century, their music vanished with them. However, Nawrot decided to explore what might be hidden away in the Jesuit Missions of Chiquitos in eastern Bolivia when he was completing his doctoral research at Catholic University of America.

To say that he “discovered” music is incorrect. In fact, local elders were well aware that music performed in the 17th and 18th centuries has survived to the present day, even performing some of it in a more or less continuous tradition. Nawrot worked with members of the community to explore this treasure trove of music once they understood that his intentions were to preserve their heritage.

Church of Concepción, Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Part of the Jesuit Missions of the Chiquitos World Heritage Site. (Photo: Bamse, CC BY-SA)

In the Chiquito missions, there are over 13,000 pages of music, including 90 polyphonic masses, vespers, litanies, lamentations, passions, hymns, chants, and materials for three operas. The score to San Ignacio is complete, while the other two operas exist only in fragments.

Nawrot explained that the opera dramatizes the “lives of St. Ignatius and St. Xavier, hoping to inspire audience members, especially non-Catholics, to adopt their virtues.” Though the manuscript materials for San Ignacio do not refer to the work as an “opera,” other historical documents, including descriptions written by those who visited the mission, indicate that San Ignacio was performed as an opera.

The missions employed dozens of professional musicians who would have provided music for daily services throughout the liturgical year, and for performances of special works like San Ignacio.

“The opera was likely performed for elite visitors to the mission in Spanish,” Nawrot said. The libretto is in Spanish, “which already tells us something. The indigenous people who saw this opera would not have understood the libretto.”

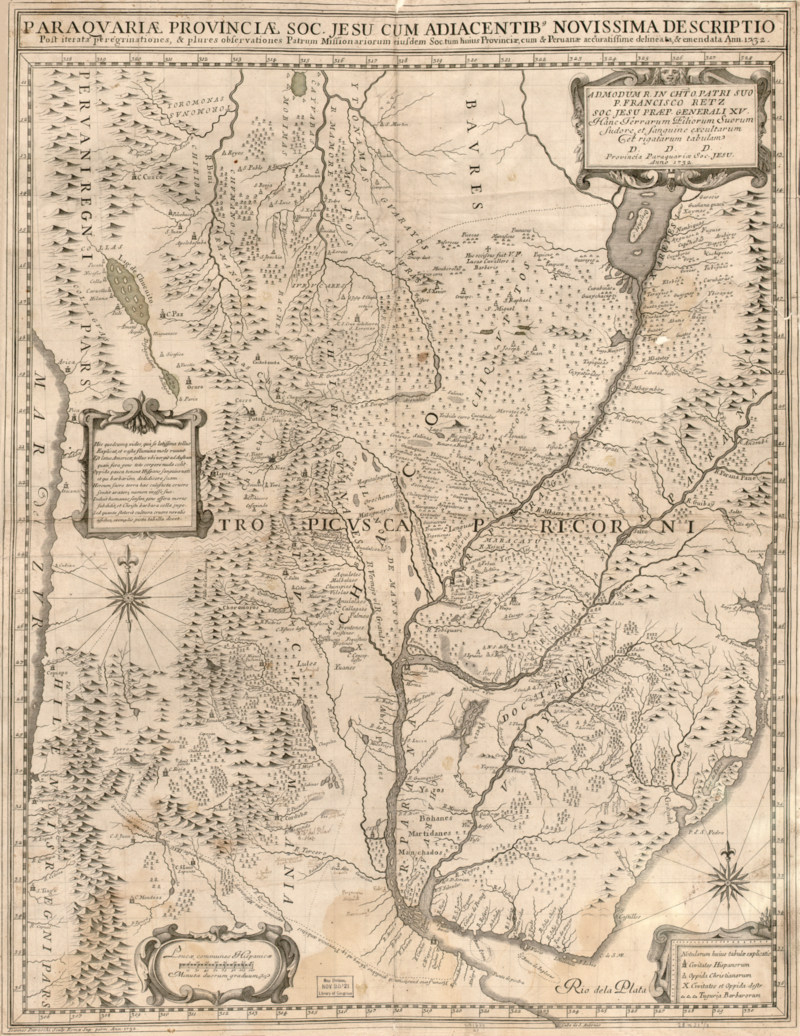

Map from 1732 depicting Paraguay and Chiquitos with the missions San Xavier (S. Xavier), Concepción (Concepc.), San Rafael de Velasco (S. Raphael), San Miguel de Velasco (S. Miguel), San José de Chiquitos (San Joseph) and San Juan Bautista (S. Juan).

Because the missions were founded to convert local people to Catholicism, he believes that San Ignacio would have been “translated into local languages for other performances. Fragments of one opera about St. Xavier in the language of the Chiquitano people provide evidence of this practice.”

Much of the music Nawrot has researched is not attributed to any specific composer, including San Ignacio. However, he believes that San Ignacio was a pastiche of music composed locally and later collated into a single work.

“For the local people, it was their own music,” he said. “They would never pretend to present the music as it was performed in Europe. They arranged the music to their own needs, using local instruments and sometimes recomposing things.” Because instruments used in the mission were built “by the local people using local materials, we know their music had its own sound.”

Interior of the church in San Javier, Ñuflo de Chávez, Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Part of the Jesuit Missions of the Chiquitos World Heritage Site. (Photo: Bamse, cropped, CC BY-SA)

Nawrot suggested that indigenous peoples governed by the Chiquito missions were fluent in multiple musical styles. “We cannot think that with religious conversion, that local people disregarded their own music,” he said. “Instead, they became culturally bilingual.”

What can you expect to hear in this multi-cultural work? The opera is composed of da capo arias and alternating recitatives, and is scored for two violins, basso continuo, and another instrument that is not identified in the score.

“The music from the missions is very beautiful and spiritual and touching. But if you’re looking for something like Handel’s Messiah in San Ignacio, you’re missing the point. Music here was used to evangelize local people, not only to show the talents of the musicians.”