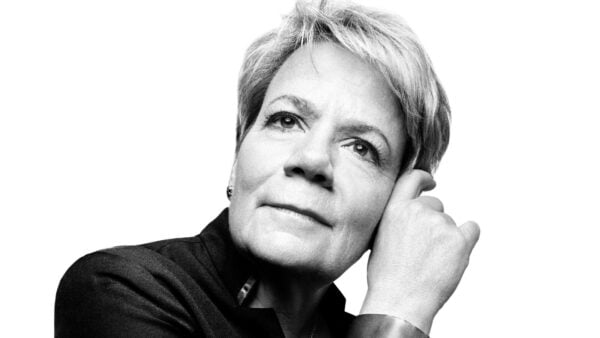

Conductor Marin Alsop (Photo: Bruno Vessiez)

When conductor Marin Alsop became the music director of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra in 2007, she was the first woman to hold this position with a major American orchestra. She’s also the first woman to conduct the Last Night of the Proms, and the first conductor ever to receive a prestigious MacArthur Fellowship. When Alsop was in the Windy City to conduct the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, she spoke about how she’s inspired young women to become conductors, why there aren’t more women on the podiums, and more.

Stephen Raskauskas: Can you tell me more about your experiences inspiring young women to pursue careers as conductors?

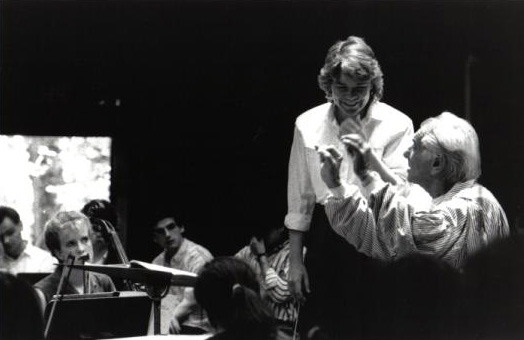

Marin Alsop: It’s great to be in the position – it’s sort of a serendipitous position – of being a role model in a way, or someone people can see as successful and giving people courage. But I think we have to be more than cardboard role models. It’s important that we all be active in mentoring and trying to change the landscape for young people. I’m a great believer in the idea that, “It was hard for me, so it can be easy for someone else.”

Marin Alsop with her mentor, Leonard Bernstein (Photo: Walter Scott)

From my perspective, I wanted to figure out: “Why aren’t there more women on the podiums?” I came to the conclusion that there aren’t enough opportunities, pure and simple. I didn’t think it was prejudice. I didn’t think it was a lack of talent. I really thought it was just opportunity. You can’t learn to conduct unless you can conduct, so you have to be able to make some mistakes. If you have one chance, and you make a mistake, your opportunities are limited.

So I started a fellowship for women conductors in 2002; so far we’ve had 11 recipients, and they’re doing fantastically well. In essence, it provides opportunities for them to conduct opening works in concerts. It’s not a huge pressure. Just one thing to focus on, and always with a mentor conductor to kind of protect them in case something is going wrong, or they need input or feedback. And out of the 11 so far, 4 are American music directors, 2 have their own orchestras that they’ve started, they’re all working. Some of them are assistants with major orchestras throughout the world. I’m very proud of them.

Raskauskas: Have you ever felt as if you have been perceived differently in your work as a queer person?

Alsop: In the arts, being gay is sort of the least unique quality one can have.

Raskauskas: Well, there are a lot of gay people in the arts, but that doesn’t mean that it’s openly talked about or that people…

Alsop: Don’t accept gay people?

Raskauskas: Yes. Even though there are a lot of gay men in the arts, I think there’s still a lot of prejudice against gay women in general in society.

Alsop: I think we tend to be at the lowest rung of the food chain. But one thing I do want to say is that from the moment the Baltimore Symphony board came to speak to me about the job, I spoke openly about my sexual orientation because I don’t want to live a life of fear. I think like my gender, like my sexual orientation, is probably the least interesting thing about me. But, that’s okay, people seem to latch onto these things. But I have to say, it was an absolute non-issue for them. Some people in Baltimore are really open-minded.

Raskauskas: Have you ever experienced discrimination throughout your career?

Alsop: I find that people’s hatred, which is what it is that people are manifesting, is really a representation of insecurity or some kind of fear. Maybe they felt excluded. It’s like a bully. When you’re bullied, you often turn into a bully yourself. Sometimes people have felt so excluded that it gives them great joy to exclude someone else, which is a really sad statement about them and maybe means they should seek help.

It’s always important to stand up to bullies. I try to teach my son that all the time. We need to protect people who are weaker; that’s why we’re here.