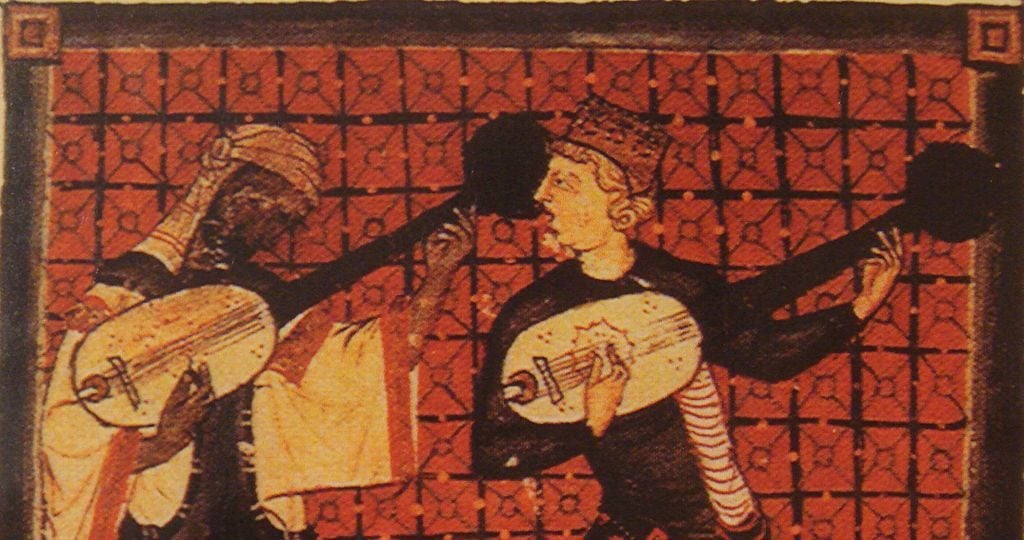

A Muslim and a Christian playing ouds in a miniature from Cantigas de Santa Maria of Alfonso X

Globalization in recent decades has led to a number of exciting cross-cultural collaborations among musicians. However, we’ve always been a global society in which the sounds of many cultures mix together to create new forms of self-expression. Ever since the Middle Ages, musicians in Europe eagerly adopted musical traditions from around the world, from as far as the Indian subcontinent to the shores of Northern Africa. In fact, one of the most influential developments in European music history may have come from Arab culture.

Troubadours and trouvères were singers and songwriters of lyric poetry who typically wrote about chivalry and courtly love. The troubadour tradition began in southern France in the late 11th century and spread to Italy and Spain during the 12th century. The female counterpart to the male troubadour is the trobairitz, while the term “trouvère” describes singer-songwriters in northern France. These composer-performers are often credited as inventing fixed forms of secular music and poetry that have evolved into some of the modern lyrical forms we still use today, such as verse-chorus form.

In a discussion of Marisa Galvez’s book Songbook: How Lyrics Became Poetry in Medieval Europe, Stanford University’s Stanford Report writes that “the European poem as we know it was invented, and fairly recently, too. What we in the West think of as poetry is largely the result of 12th-century troubadours and their controversial insistence on singing about the profane. The troubadours introduced the concept of courtly love and invented poetic forms still in use today…”

A depiction of William of Aquitaine, the first known troubadour, in a manuscript.

These early singer-songwriters were not a strictly European phenomenon, however. Though it’s still a subject of contentious debate today, many music historians and medieval scholars believe these European poet-composers derived their literary and musical forms from the Arab world. Specifically, Andalusian poetry – that is, poetry written in Spain during periods of Islamic rule – may have laid this groundwork for the troubadours.

In an essay titled “Troubadour Poetry: An Intercultural Experience,” Said I. Abdelwahed, a professor of English at Al-Azhar University in Gaza, argues that Arabic love poetry “established itself swiftly and flourished in Andalusia, then it spread into southern France and other parts of Europe,” effectively shaping the history of European poetry.

The word “troubadour” itself bears striking resemblance to the Arabic word “tarab,” which translates to “mirth” or “joy” in English. Given the often playful nature of troubadour songwriting, some believe Arabic language and culture are essential to troubadour history. Others believe these similarities are merely coincidental, pointing to the Old French “to find” as troubadour’s etymological root.

Judith A. Peraino, in her book Giving Voice to Love, examines fixed forms of music and poetry that were common during the Middle Ages. She shows some similarities between fixed forms used in Arab music and poetry, such as muwashshah and zajal, and secular forms in Europe, such as the Spanish cantiga. These “Arab origin theories” to explain the sources of fixed forms of music and poetry in Europe have been circulating since at least the late 1970s, when Roger Boase published his book The Origin and Meaning of Courtly Love: A Critical Study of European Scholarship.

There is even some speculation that William of Aquitaine, who is largely credited as the earliest troubadour, transcribed four Arabo-Hispanic verses nearly verbatim in one of his manuscripts. William, also a military leader fighting on behalf of the Christians during the Iberian Reconquista, may have learned Arabic from his prisoners and adversaries. (His granddaughter, Eleanor of Aquitaine, was famous for nurturing music and poetry in her “court of love” at Poitiers, as well as for her role in the Second Crusade.) Hear a work by William of Aquitaine below.

And compare it to a Hispano-Arabic work from the 12th century:

The rebab, a predecessor to the violin. (Tropenmuseum, part of the National Museum of World Cultures / CC BY-SA)

There are conflicting theories about how the practices of troubadours, trouvères, and trobairitz developed. But existing evidence makes a strong case that some of their innovations came from Arab culture. After all, it’s not only musical forms that have come to Europe from other parts of the world. Many instruments trace their long lineage back to the Middle East and Northern Africa. The violin descended from the rebec, which in turn developed from the rebab.

And of course, Europeans didn’t just adopt artistic practices from other cultures; many fields of study, from architecture to algebra to astronomy, are indebted to major advances made by Arab scholars. So much of what we think of as “Western” music may not even be so “Western” after all.