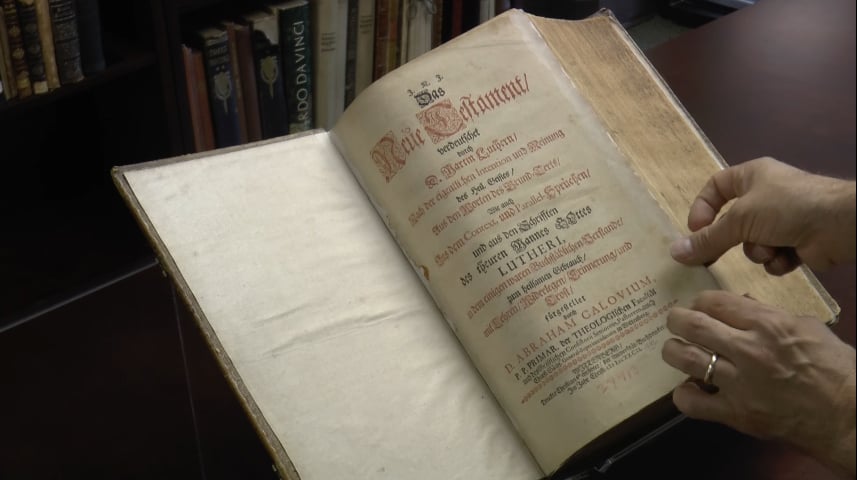

A volume of Bach's Bible on display at Concordia University as part of "Let the Books Tell the Story: J.S. Bach's Bible & Reformation Treasures"

Though J.S. Bach wrote many sacred works, some historians have questioned his faith. Notes Bach made in his own personal copy of the Bible may reveal whether or not the composer was truly religious.

From 1723 until his death, J.S. Bach served as the music director of the Lutheran St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, Germany. The reformer Martin Luther preached at St. Thomas almost two centuries before Bach composed sacred music there.

Music historian Robert L. Marshall claims that starting in the late 1720s, Bach showed a “growing disengagement from his regular church duties.” In 1730 he complained to the town council of Leipzig that he did not have adequate resources to do his job. Shortly after, he was criticized for showing “little inclination to work” by a member of the council.

A statue of J.S. Bach in Leipzig, Germany, outside of the St. Thomas Church where he worked for a substantial period of his career and until his death (Photo: Zarafa, CC BY-SA 3.0, image cropped, via Wikimedia Commons)

In the early 1730s, J.S. Bach became increasingly interested in composing for the Saxon court at Dresden, a center for music and opera at the time. He even composed parts of his B Minor Mass for the Catholic Elector of Saxony, perhaps with the hopes of leaving his low-paying church job in Leipzig. According to Bach scholar Tim Smith, Bach’s Leipzig salary was the equivalent to what the average metal worker or stone mason would make today.

So was Bach composing sacred music simply to support his family? Or were his religious convictions sincere?

Bach’s Bible may have some clues.

Bach’s Bible is a special edition known as the Calov Bible. It was printed in the late 17th century and contains German translations as well as commentary by Martin Luther and theologian Abraham Calovius. Bach took notes in the margins, occasionally noting errors. One correction Bach made is particularly revealing about the composer’s possible religious convictions.

He noticed that in Mark, Chapter 10, half of verse 29 and all of verse 30 were omitted. Robin Leaver, author of J.S. Bach and Scripture claims, “Here is an indication of Bach’s concern for the integrity of the Biblical text…Significantly, verse 30 speaks about the spiritual recompense the believer can expect in return for enduring difficulties and persecution for the sake of Christ and the Gospel. In all his disputes Bach would feel somewhat persecuted, and there may well be here an indication of the solace he found in the Word of Scripture that pointed him to Christ and the importance of the Gospel.”

Bach signed the title page of his Bible with the year 1733, the same period Robert L. Marshall claimed the composer showed “growing disengagement” from his work composing sacred music in Leipzig.

Bach also made special notes in his Bible about passages that mentioned music. In the margins of II Chronicles 5:13, which describes how music aids worship, Bach wrote: “Where there is devotional music, God with His grace is always present.”

WFMT got a look inside Bach’s Bible while it is on display at Concordia University Chicago as part of Let the Books Tell the Story: J.S. Bach’s Bible & Reformation Treasures, an exhibit on display from October 8 – November 7, 2017. Take a look inside Bach's bible yourself by watching the video below.

Let the Books Tell the Story: J.S. Bach’s Bible & Reformation Treasures displays a volume of Bach’s Bible, on loan from Special Collections, Concordia Seminary St. Louis, as well as other rare books and documents from as early as the late 15th century. In addition to books related to music and the fine arts, the exhibition displays important theological texts, including a leaf from the Gutenberg Bible (1454), the Luther Bible (1534), and the Biblia del Oso (1569), the first complete Spanish translation of the Bible. The exhibition is part of is part of Concordia University Chicago’s celebration of the 500th Anniversary of the Reformation.For more information, visit Concordia University Chicago’s website.