Frida Kahlo and Chavela Vargas circa 1945 (Photo: Nickolas Muray, Public Domain, color added, via Flickr)

The name Frida Kahlo is closely associated with Diego Rivera. Though Kahlo married Rivera (twice), she had many affairs, including with photographer Nickolas Muray, artist Isamu Noguchi, and revolutionary Leon Trotsky. But Kahlo, one of Mexico's most iconic painters, may also have had a relationship with one of Mexico's most iconic singers, Chavela Vargas.

"Everybody knows who Chavela Vargas is, not everyone is conscious of (or wants to talk about) her queerness," says Ana R. Alonso-Minutti, a professor of music at the University of New Mexico. Some of Alonso-Minutti's current research explores the relationship between Vargas and Kahlo.

Vargas, born in Costa Rica in 1919, made Mexico her adopted home in the 1930s. "Sometime in the early 1940s," recounts Alonso-Minutti, "Chavela was invited to a party at the Casa Azul," the house in Mexico City where Kahlo was born and lived most of her life. "Apparently, at the end of the party, Frida invited Chavela to stay overnight because Chavela lived in a different part of the city. They started this relationship that was very intense."

Chavela Vargas (Photo: Ysunza, courtesy of Music Box Films)

Chavela is known for singing canciones rancheras, traditional Mexican songs typically performed by men, while dressed like a man. The singer "queered conventions by presenting herself not in feminine attire, but with poncho, trousers, sandals, hair up, no makeup," Alonso-Minutti says. "Then she sang with this raspy, masculine voice, and she would sing to the women in the audience. She did not hide her sexuality; she was very open about it."

Though Vargas challenged conventions, she did not publicly come out as a queer woman until she published her autobiography, Y si quieres saber de mi pasado (And if you want to know about my past), in 2002 at the age of 81. She also wrote about her life in the 2009 autobiography Las Verdades de Chavela. Among the many lovers that Vargas had, Kahlo is the only one to whom she devotes an entire chapter in her autobiographies.

The most detailed account of their relationship, however, comes from an interview included as a special feature on the DVD of Julie Taymor's 2002 biographical film Frida. Chavela tells Elliot Goldenthal, who composed music for the film's score, how she came to know Frida, and describes her as "mi gran amor" ("my greatest love"). In the interview, Vargas also recounts that at one point the relationship was so intense that Frida said, "I gave birth to you."

Alonso-Minutti claims that "the idea of being born of Frida and having Frida's blood running through her own blood gives us a sense of the deep, deep, intense relationship between both of them. There's a lot of speculation about these love stories. When Chavela is asked about this she says, ‘Well, whoever wants to find out my story should open my chest and find my memories,' because she allegedly burned many letters that Frida wrote to her."

Visita revistacentral.com.mx to see one letter Kahlo allegedly wrote to poet Carlos Pellicer, in which the letterwriter describes Vargas as "an erotic woman" that she desired.

"Hoy conocí a Chavela Vargas. Extraordinaria, lesbiana, es más, se me antojó eróticamente. No sé si ella sintió lo que yo. Pero creo que es una mujer lo bastante liberal que si me lo pide no dudaría un segundo en desnudarme ante ella…¿Acaso es un regalo que el cielo me envía?" Attributed to Frida Kahlo

“Today I met Chavela Vargas. An extraordinary woman, a lesbian, and what’s more, I desire her. I do not know if she felt what I did. But I believe she is a woman who is liberal enough that if she asks me, I wouldn’t hesitate for a second to undress in front of her… Was she a gift sent to me from heaven?”Attributed to Frida Kahlo

However, Hilda Trujillo Soto, the current director of the Casa Azul, the Frida Kahlo Museum in Mexico City, later questioned the letter's authenticity. While photographs make it unquestionable that Vargas and Kahlo knew each other, the exact length and nature of their relationship will never be certain.

Alonso-Minutti is more fascinated by ways in which their relationship may have created a lasting impact on Vargas and her music. "Apparently, Chavela would sing endless songs for Frida while Frida painted," she says, "and one of Frida's favorites was 'La llorona,' ('The Weeping Woman')," a Mexican folk song popularized, in part, by Vargas.

The song describes one version of the legend of La Llorona, in which "a figure who is betrayed by her male lover and, out of anger or revenge, she kills her children by drowning them in a river," recounts Alonso-Minutti, "Then she is condemned to anger and solitude for eternity, weeping for the death of her children."

In recent decades, Chicana feminists and scholars have retaken La Llorona as a character that rejects how heteronormative patriarchal society forces women to serve as mothers and endure abuse by men, including abandonment. "It's very interesting to look at the life of Frida Kahlo in that lens," Alonso-Minutti says. "As we know, Frida couldn't have children; she had an abortion, she had a miscarriage, and she mourned the death of her unborn children. Her body kind of killed her unborn children. She was in immense pain from the accident she had when she was 18."

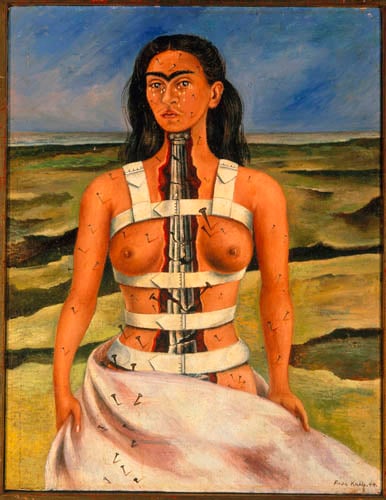

Frida Kahlo's The Broken Column (1944). Collection Museo Dolores Olmedo, Xochimilco, Mexico City, Mexico (Photo: Banco de México Diego Rivera-Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy of Schalkwijk/Art Resource, NY)

When Chavela sings "La llorona," Alonso-Minutti claims she is singing to and about Frida. "She is an other-worldly lover. I think Chavela also identified herself as a 'rara' ('a weirdo'), and she articulates her own sexuality as one of 'raressa' ('strangeness')."

The song "La llorona," like the legend itself, does not exist in a single version. Singers have the freedom to choose the verses they include in the version they sing. Alonso-Minutti argues that when Vargas performed this song throughout her career, she improvised verses in which she articulates her feelings about Frida. Since Vargas saw herself as being born of Kahlo, Alonso-Minutti also says, Frida saw herself as La Llorona, too.

The Broken Column, the only self-portrait of Kahlo that Vargas describes in her own writings, also may connect the painter to the figure of La Llorona. Alonso-Minutti mentions that in this painting, Frida has depicted herself as a Llorona, "she is weeping in a barren landscape. There's also very interesting religious symbolism – she's pierced with nails, which could be an allusion to Christ on the cross. There's also a little white sheet that covers her body, which is also related to depictions of Christ on the cross."

Unsurprisingly, Vargas insisted in being a part of the production of Taymor's film Frida, in which she appears singing "La llorona." Watch an excerpt below.

Though Vargas had begun her career in the cabarets of Mexico City, by the end of her life she was singing on the world's greatest stages, including Carnegie Hall. As a musician, she became a household name. But she had also become "a kind of grandmother figure to a whole generation of queer people in Mexico," Alonso-Minutti says. Yet she also reminds us: "A lot of Mexican audiences do not necessarily acknowledge her sexuality. For example, there are people in my family who are not consciously aware that she was a lesbian."

In that sense, Vargas is also the grandmother to younger generations of Mexican performing artists who may present a public persona that fans perceive as queer, but who may not speak directly about their sexuality or other aspects of their private lives.

The alleged homosexuality of popular singer Juan Gabriel was a "secreto a voces" ("open secret") in Mexico for decades. In 2002, when Univision reporter Fernando del Rincón asked Gabriel if he is gay, the singer responded: "Dicen que lo que se ve no se pregunta, mijo" ("They say, don't ask what you know the answers to").

Fans have also speculated about the sexuality of balada singer Ana Gabriel. In "Simplemente Amigos" ("Only Friends"), Gabriel sings, "Cuanto daría por gritarles nuestro amor / Decirles que al cerrar la puerta nos amamos sin control" ("What I would give to shout to everyone about our love/To tell them that behind closed doors, we love each other without control.") In 2015, Gabriel allegedly addressed her sexuality when she told fans at a performance in Monterrey, Mexico, "I'm better off being asexual, just like the angels."

Unlike some however, Vargas did not hide her sexuality – at least at the end of her life. Vargas was also clear about her feelings for Kahlo – though we cannot be certain about how reliable her accounts of their relationship are.

Photographic evidence we have of them together indicates that they must have had some affection for each other. But if their relationship was so intense, why did it end? Alonso-Minutti speculates that "Frida was 15 years older than Chavela, who was just starting to make her way in life and her career, and I think Chavela needed to kind of depart from the safe haven of Caza Azul to find her own voice, her own path."

In the interview between Vargas and composer Elliot Goldenthal, the singer said that when she left Frida, Frida was sad, but asked that she always remember her. Perhaps, Vargas also remembered her through her rendition of "La llorona."

Editor's note: This story has been updated from an earlier version with accuracy, spelling, and media elements.