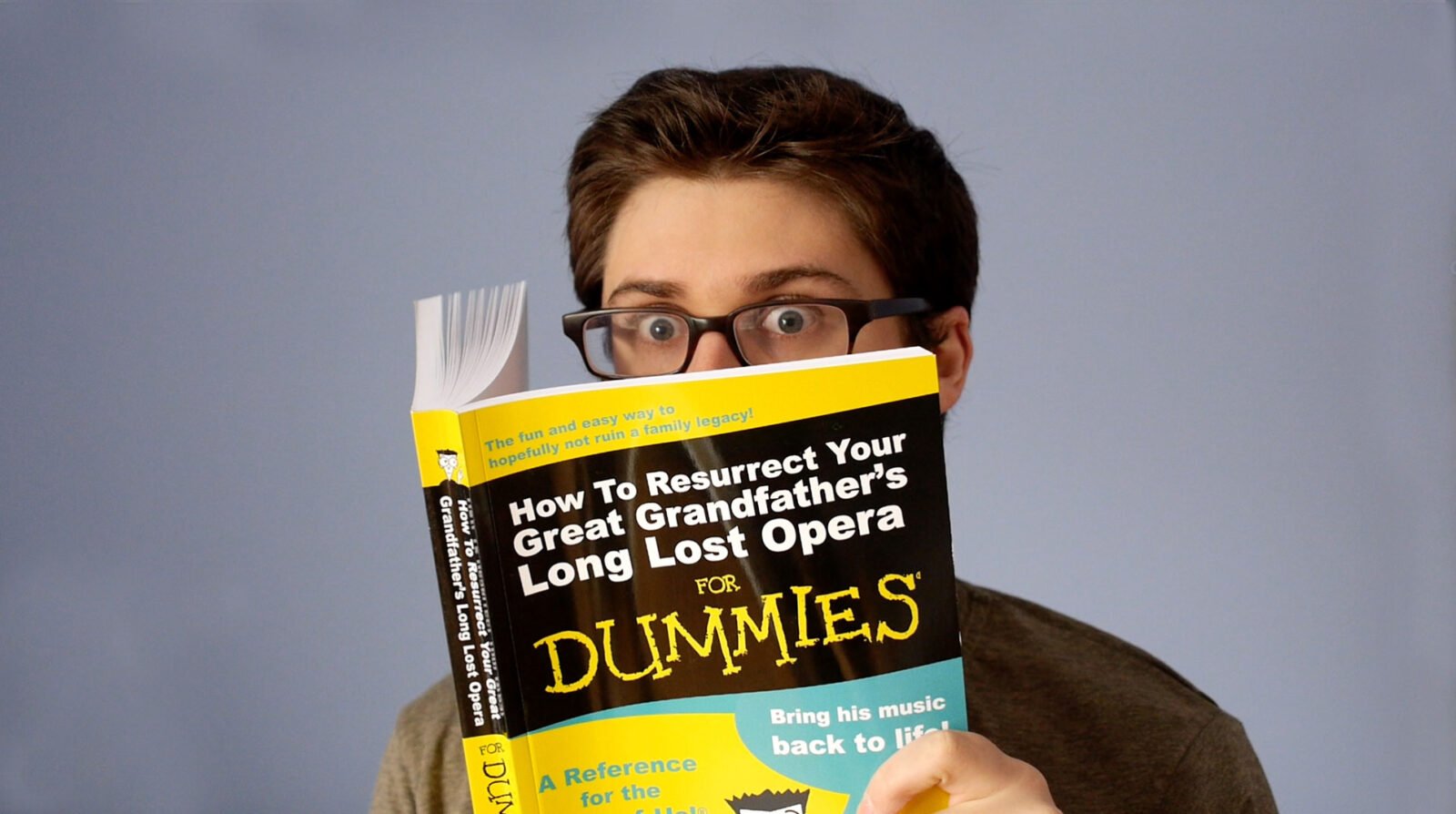

Arlen Parsa, who has resurrected the opera "Andina" by his grandfather Eustasio Rosales

Andina, a long-lost opera composed by Eustasio Rosales, received its long-overdue world-premiere in Chicago after being discovered by the composer’s great-grandson, Arlen Parsa.

Parsa said in a recent interview that while he and his family knew Rosales was a professional composer and musician, “we always assumed his music died with him.” That is, until one day, when his aunt discovered two boxes containing a full score of an opera called Andina, a “crumbling” piano-vocal reduction of the score, and a handwritten English translation of the Spanish libretto.

The story of Andina, composed in the 1930s, takes places in the foothills of the Andes. The main character, Rosa, is a “beautiful, naïve mountain girl, and she has two suitors: one is Juan, who is a simple, local farm hand, and the other is Don Carlos, who is a wealthy plantation owner from the city,” Parsa said.

The opera’s plot doesn’t stray too far from the “girl meet boy, girl must choose between two boys” formula of many operas. But, the opera’s journey from page to stage is anything but typical.

Rosales was born in Columbia during the 19th century, where he composed his first symphonic work at the tender age of 12. He came to Chicago shortly after the World’s Columbia Exposition of 1893. “He fell in love with Chicago, and decided he wanted to move there,” Parsa explained.

“His family had a little bit of money, but he didn’t bring any of that money with him, so he had to struggle with a lot of musical odd jobs,” Parsa said. Besides composing and arranging music, Rosales also accompanied silent films. “When movies with sound came along, he was out of a job,” Parsa said matter-of-factly.

One of the many hats Rosales wore was band director. He led his own ensemble, the Señor Rosales Latin Band, pictured below performing on the rooftop patio of the no-longer standing LaSalle Street Hotel. Ironically, Parsa said that none of the members of Rosales’s band were Latino: they were all Germans!

Eustasio Rosales conducts his band

The music they played likely included what he composed or arranged himself. Some of his published arrangements of popular songs still exist in libraries around the world, like “Princess Pocahontas,” a march and a two-step, and minstrel songs like “Massa’s in de cold ground.”

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra also performed some of his music. A visit to the CSO’s Rosenthal Archives revealed that “in 1932 [Rosales] composed Three Spanish Dances for the CSO, which may be the first piece the orchestra performed by a Latin American composer.”

When Parsa found a review from the Chicago Daily News, it mentions he was pulled on stage to receive standing ovations, which “gave me hope that maybe this long lost opera would be good, because I really didn’t know.”

However, since Parsa, a documentary filmmaker, has limited knowledge of opera, he enlisted the help of composer Pablo Chin to create a modern edition of Andina. While this seems like a relatively simple task, Chin had to reconcile occasional differences between his various sources – the full score, piano-vocal score, and libretto – to determine what the composer originally intended.

Luckily, Rosales had “pretty nice handwriting,” Chin explained in a recent chat on the phone. But, there were other problems that had to be solved. “The lyrics were difficult to decipher,” he said. ”The language is very old-fashioned Spanish. I mean, I speak Spanish and it was hard even for me!”

Occasionally, Chin encountered other editorial issues that he had to reconcile. For example, “some tempo markings were clearly erroneous,” Chin said. “He might write something like allegretto, but then he would also write that a quarter note equals something like 44 beats per minute [a very, very, slow tempo].”

The excerpt above is from one of the final rehearsals of Andina before it receives first performance in Chicago.

The score includes traditional instruments one might find in an early 20th century opera pit orchestra: strings, piccolo, flutes, oboes, English horn, clarinet, bass clarinet, bassoons, horns, trumpets, trombones, tubas, and harp.

But, unlike other opera scores of the time, Andina requires quite the percussion section. In addition to timpani, tambourine, cymbals, triangle, gran cassa, the score calls for Spanish and Latin American percussion instruments including castanets, tamburo, and tam tam!

The instrumentation is indication enough that Rosales’s score blends both European and Latin American musical traditions. Chin also mentioned that Andina contains some dance movements, showing, perhaps, the influence of other Latin American genres like zarzuela.

The cast of Andina

Though Parsa and Chin began to piece together the puzzle of Andina, one thing the opera desperately needed was money. Parsa launched a successful fundraising campaign on Kickstarter to support the first performances of the opera featuring the Chicago Composers Orchestra and led by conductor Chris Ramaekers.

“The very first time I heard this music I was terrified, because I didn’t know what it was going to sound like,” Parsa confessed. “And as a young person who’s much more comfortable listening to Kanye than Beethoven, I thought I was going to hate this music. I was afraid I wasn’t going to be able to relate to this at all. But much to my surprise, when we did the first read-through with just piano and five singers, I was kind of spellbound by it. It’s really romantic and it’s soaring and it’s kind of cinematic.”

You can learn more about Andina in a new documentary, Lost Opera: The Way to Andina, that premieres on WTTW11 on January 25, 2018 at 9:00 pm.