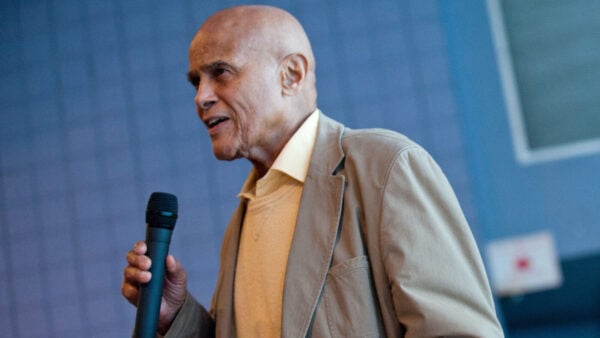

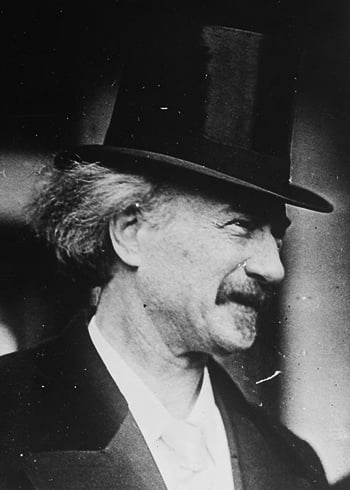

Ignacy Jan Paderewski addresses a crowd, ca. 1915 (Bain News Service, via Library of Congress)

As a pianist, composer, statesman, and philanthropist, Ignacy Jan Paderewski embodied the idea of the Renaissance man in an undeniable way. Few other star concert pianists can boast that they fought for — and helped win — their country’s independence.

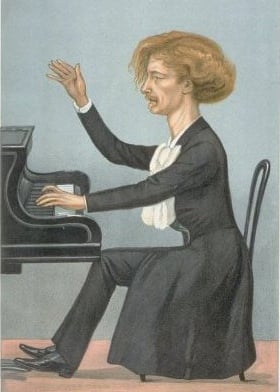

This caricature of Paderewski appeared in Vanity Fair in 1899. Leslie Ward [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

One particular story seems to capture the height of his celebrity. He was close friends with Theodore Thomas, the founder and first music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. As the Rosenthal Archives of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra detail, Paderewski performed at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, headlining the inaugural concert with the Exposition Orchestra under Thomas’s baton. He performed his own Piano Concerto in A minor and Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto.

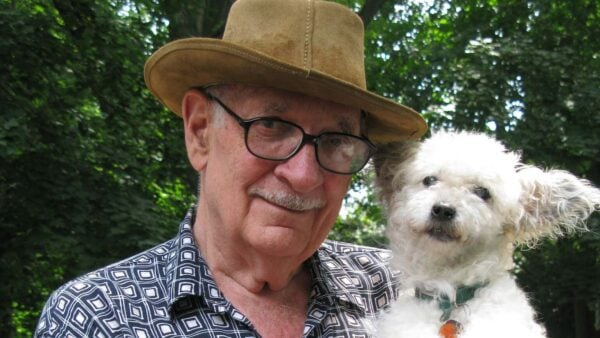

Theodore Thomas, the founder and first music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (Photo: A. Cox from the collections of the Rosenthal Archives of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra)

The performance was scandalous, but not because of the program. Under Thomas’ leadership, the exposition favored Midwestern piano builders out of respect to its Chicago setting. Steinway, a New York company, was one of the builders that took exception to this decision, and they withdrew from the exposition.

However, as the CSO Archives note, Paderewski was “unofficially an exclusive Steinway artist and if he was going to perform, it had to be on a Steinway.” So, the night before the first performance, workers actually snuck a Steinway grand piano into the concert hall. Though he had had no knowledge of the switch, Thomas was rebuked by the exposition’s committee and was besieged with negative publicity from the local press.

The Court of Honor, the centerpiece of the World’s Columbian Exposition. C. D. Arnold (1844-1927); H. D. Higinbotham [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons (image cropped and contrast adjusted)

Paderewski, ca. 1915 (Bain News Service, via Library of Congress)

Despite this scandal, one of the high marks of Paderewski’s musical career came in 1901, when his opera Manru premiered. The opera is adapted from a Polish novel and tells the story of a gypsy man’s failed marriage to a Polish peasant in the Tatra Mountains along the Polish-Slovakian border. The opera tackles themes of intolerance in Poland. Scholars have argued that it pulls from a wide range of operatic forbearers, including Richard Wagner, Giuseppe Verdi, and Georges Bizet. As of publication, Manru is still the only Polish opera that has been performed at the Metropolitan Opera.

Paderewski was also a passionate patriot. Because he was so well-traveled and his playing was so celebrated, he was well connected in the international community. Before the war, Paderewski funded a monument in Krakow commemorating the 500th anniversary of a critical Polish military victory. Throughout the 1910s, he became an increasingly visible and respected spokesperson for Polish independence.

He was a member of the Polish National Committee, which lobbied the Entente Powers (the coalition that included the US, France, and the UK which opposed Germany and its allies in World War I) to support Polish statehood in exchange for military aid. In the committee, he was appointed to represent the committee to the US. He convinced American officials, including President Woodrow Wilson, to support Polish independence. Paderewski wrote an impassioned essay advocating for an independent Poland, which helped influence President Wilson to include Polish independence and autonomy as one of his famed Fourteen Points.

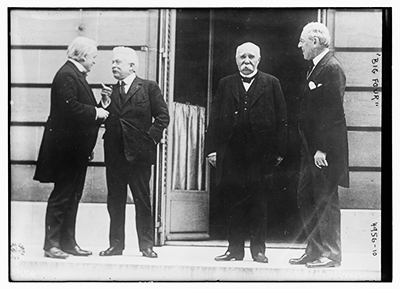

The Big Four: (L-R) Prime Minister David Lloyd George of the UK, Premier Vittorio Orlando of Italy, Premier Georges Clemenceau of France, and President Woodrow Wilson of the US (Bain News Service, via Library of Congress)

After the Armistice, Poland gained its independence, and Paderewski became the Prime Minister and the Secretary of Foreign Affairs (in Poland, the Prime Minister is not the executive head of state but rather the leader of the cabinet). In these positions, he was an important figure in the peacemaking process and one of the most outspoken and recognizable members of the Polish delegation. The virtuoso-turned-statesman signed the Treaty of Versailles and then oversaw its domestic ratification.

Through his efforts at the Paris Peace Conference and his eloquent rhetoric at the League of Nations, Paderewski was praised in the international community. The leaders of the US, the UK, France, and Italy, dubbed the Big Four, are said to have commended Paderewski, and declared, “No country could wish for a better advocate” in a jointly-written letter.

Paderewski left politics in 1921 and returned to music. However, even removed from political life, he remained politically engaged. He continued to serve through philanthropic acts, and he supported a wide range of causes including music and arts education, Jewish refugee communities, and programs for veterans.

In 1941, just one week before he died, he gave a speech to Polish veterans in the United States, and said the following: “I don’t know if my fate will allow me to see [the birth of] Poland, but I deeply believe that for you and for your children the country will be a source of pride and joy.”

Paderewski’s exceptional life is one of the stories highlighted in A Time For Reflection—A Message of Peace, an exhibit commemorating the Armistice centenary through the lens of the Chicago and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

The exhibit was curated by the Rosenthal Archives of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and its director, Frank Villella, in collaboration with the Pritzker Military Museum & Library. The exhibit is free and on display in Symphony Center’s first-floor rotunda through November 18. The exhibit content can also be viewed in the From the Archives blog.