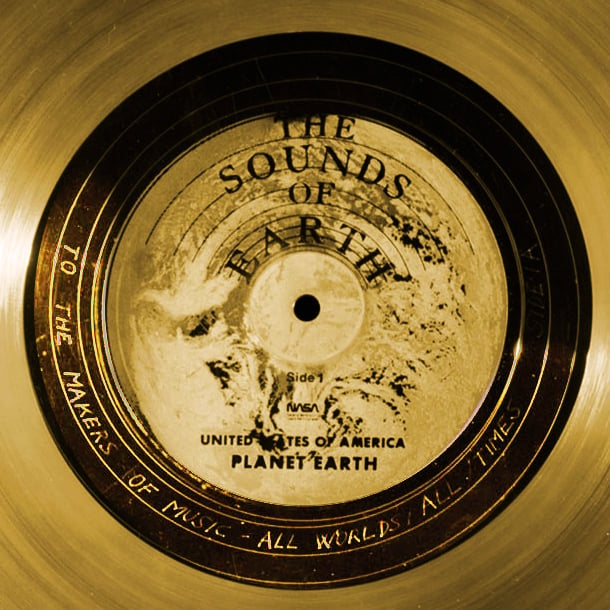

If given the task to assemble a collection of music that reflects humanity, what would you choose? This assignment was given to a group of astronomers, science writers, designers, and engineers. Their solution? The Voyager Golden Record: a collection of images, sounds, greetings, and a diverse array of music.

If given the task to assemble a collection of music that reflects humanity, what would you choose? This assignment was given to a group of astronomers, science writers, designers, and engineers. Their solution? The Voyager Golden Record: a collection of images, sounds, greetings, and a diverse array of music.

Astrophysicist and Cornell University professor Carl Sagan led the Voyager Golden Record team. Sagan once noted, “It bears a message. A phonograph record: golden, delicate, with instructions for use. And on this record are a sampling of pictures, sounds, greetings, and an hour and a half of exquisite music. The Earth’s greatest hits. A gift across the cosmic ocean from one island of civilization to another.”

Science writer, filmmaker, and Pulitzer Prize nominee Timothy Ferris was the producer of the Voyager Golden Record. “Well, if you're going to make a record that shows off some of the richness and diversity of the world's music I think it would be perverse not to include classical music, which is in many ways the highest realization of human music,” says Ferris in a phone interview with WFMT.

Timothy Ferris

The idea to incorporate a phonograph record on the Voyager mission began with Carl Sagan and astronomer Frank Drake. Tasked with the mission of exploring the outer solar system, the Voyager spacecraft would be wandering space forever. Initially, the thought was to simply add a plaque on the spacecraft that said something about humans.

But the two realized that a phonograph record, with the same weight as a plaque, could carry within its grooves a lot more information.

“One evening, Carl was at my place in New York and we were listening to music,” Ferris recounts. “Carl and Frank had this idea to put a record on the Voyager spacecraft, and he asked if I wanted to be part of the project. Since my two principal interests have always been astronomy and music, it was perfect for me, and I agreed.”

Once NASA approved the project, there were just a few months to put the record together. A small team, including some of Ferris’ friends and colleagues, quickly began the musical selection process. With Ferris, Drake, and Sagan, the team consisted of artist Jon Lomberg, artist Linda Salzman, author Ann Druyan, ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax, and music producer Jimmy Iovine, an accomplished recording engineer who had worked with John Lennon.

Ferris explained the difficulties of acquiring the music, a challenge probably unfamiliar to music enthusiasts in the digital age. “You had to get physical copies of the tapes and records. Nowadays, music and content can be delivered though a link in the cloud at the speed of light, but back in the ‘70s, it had to be physically assembled. Being in New York City helped.”

“We would have listening sessions at my place in New York, at Carl's place in Ithaca, and everyone would come up with candidates. It was a rather informal process,” says Ferris. “We would sit for hours listening to stuff and thinking about how to assemble a portrait of the earth in musical terms. Some of the strongest pieces were suggested early on because they were pieces that had a tremendous meaning to someone. ‘Dark Was the Night’ by Blind Willie Johnson was a suggestion of mine at the first meeting. Chuck Berry was also an early suggestion by Ann Druyan.”

Ferris recounts, “I did want to represent some major composers to show the relationship between classical music and mathematics. Bach, Beethoven, and Mozart provided a mathematical resonance that might mean something to extraterrestrials, to whom the music might conceivably be otherwise uninteresting.”

The Voyager spacecraft showcasing where the Golden Record is mounted. (Photo: NASA/JPL)

In an article Ferris wrote in The New Yorker, he explained that this mathematical perspective came because they realized extraterrestrials studying the records might hear on a different frequency range from humans, or altogether lack what we call hearing. The thought was that the music could be studied by applying mathematics — by picking apart symmetry and repetition in compositions.

Ferris explained why certain artists did not make the cut. “Bob Dylan's a great poet, but we can't really expect the strength of English poetry to convey on the same level that music might do in its terrestrial audience. The Beatles song 'Here Comes the Sun' was a suggestion because it was witty. I did not think it was that great a joke because the sun was not coming to the aliens, the spacecraft was coming to the aliens, plus I thought the joke had already gotten stale.”

The inscription on the Voyager Golden Record (Photo: NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory)

Ferris says that John Lennon influenced the production process. “I wanted John to be involved, but he had to leave the country and turned it down. I was sorry that John wasn't involved in the project, but he did contribute two things: the idea of the inscriptions, and the suggestion that we use Jimmy Iovine as our engineer.” Inspired by Lennon’s trick of etching messages onto records, Ferris hand-etched an inscription on the Golden Record that reads, “To the makers of music — all worlds, all times.”

The team completed the selection process in time for NASA’s launch of the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft at the end of summer 1977. Mounted in aluminum containers with cartridge and needle, a gold-plated copy of the Golden Record accompanied each Voyager spacecraft. Each Golden Record also included diagrammtic instructions to play at 16 and 2/3 RPM.

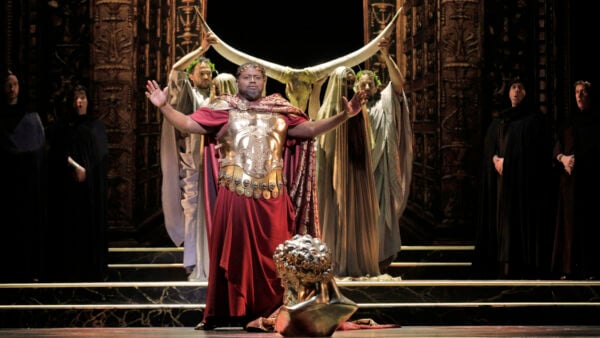

The final, eclectic 90-minute musical playlist of Earth includes folk and world music from Peru, New Guinea, and Senegal; Chuck Berry; Louis Armstrong and his Hot Seven; and classical pieces by J.S. Bach (interpreted by Glenn Gould), Mozart (Bavarian State Opera), Beethoven (Philharmonia Orchestra), and Stravinsky (Columbia Symphony Orchestra). Each Golden Record also includes images encoded in analog format; greetings in 55 languages from various cultures and eras; and sounds from planet Earth including laughter, thunder, a train, animal sounds, the sound of a kiss, and a human heartbeat.

"I can guarantee the outer side of the Voyager Golden records for at least a billion years and the inner side, which is more protected from cosmic rays, at least two billion years. If it fails before that time, bring it back to the shop,” he jokes.

“I suppose the interest in knowing more about vast parts of nature far away is as inexplicable as liking music,” Ferris muses. “We wanted to make a record that represented the enormous diversity of humans, as well as the quality of the work they can produce. I think we managed to do that. I always say the Voyager is more about time than it is about space. It just drifts out there. It really is like a note in a bottle.”

This interview has been edited for clarity. For more information about the Voyager Golden Record contents, visit nasa.gov

We put together a playlist featuring the music on the Voyager Golden Record. Enjoy below!

Please note: "Bhairavi: Jaat Kahan Ho" performed by Kesarbai should come after Flowering Streams. Unfortunately, this song is not on Spotify.