“Nature is always more subtle, more intricate, more elegant than what we are able to imagine.”

“Nature is always more subtle, more intricate, more elegant than what we are able to imagine.”

― Carl Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark

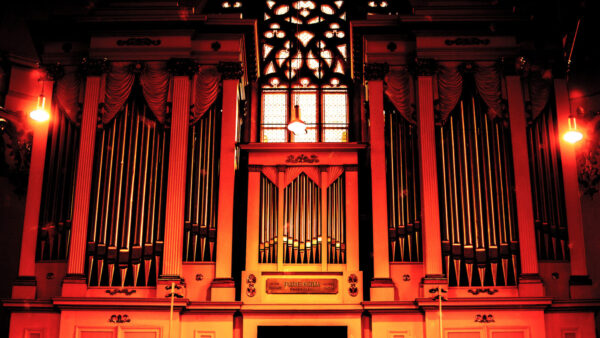

The human hand: its fingers, bones, muscles, and more give us the ability to add a pinch of salt, play any number of musical instruments, change a tire, flip a pancake, and so much else. That our hands have the capacity to perform these movements repeatedly and without thinking about them is due to muscle or motor memory.

But suppose a hand were transplanted from another body. Could it—would it—retain unthinking memories created with that original body? If you were to ask Hollywood, the answer is a very blood-curdling scream of “YES!” As Halloween approaches, let’s look at a few horror films in which pianists, or at least the hands they are attached to, are the stars.

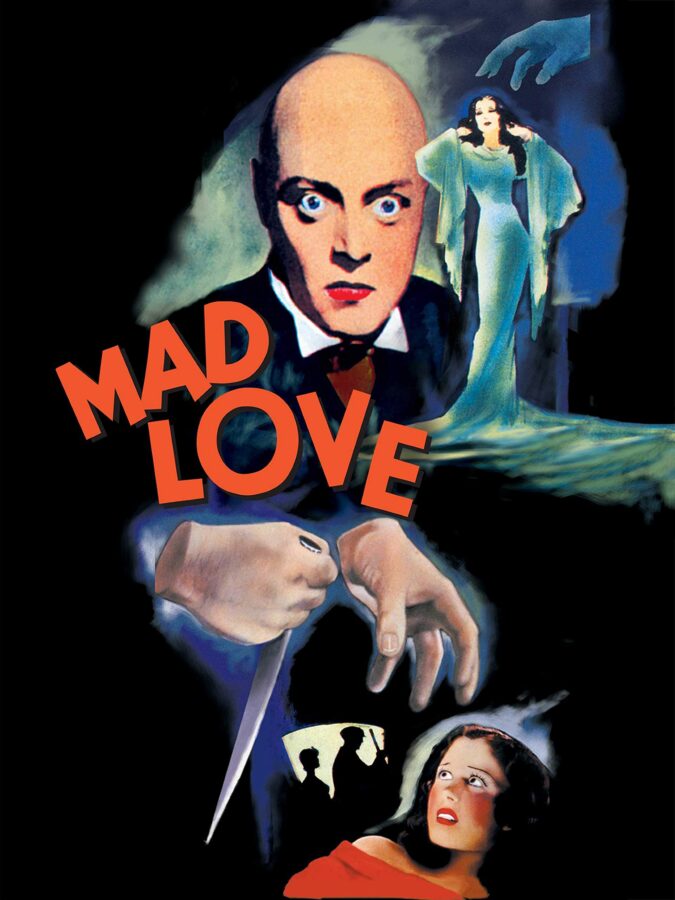

In his first American film, 1935’s Mad Love, Peter Lorre (best known for roles in Casablanca and The Maltese Falcon) played a half-mad scientist, Dr. Gogol. This odd, but well-respected, doctor has an obsession: Yvonne Orlac, a young actress who performs in a theater specializing in naturalistic horror shows, quite like Paris’s Grand–Guignol. When Yvonne announces that she and her husband, famous pianist Stephen Orlac, are moving to England, Dr. Gogol experiences his first crisis. “I, a poor peasant, have conquered science. Why can’t I conquer love?”

In his first American film, 1935’s Mad Love, Peter Lorre (best known for roles in Casablanca and The Maltese Falcon) played a half-mad scientist, Dr. Gogol. This odd, but well-respected, doctor has an obsession: Yvonne Orlac, a young actress who performs in a theater specializing in naturalistic horror shows, quite like Paris’s Grand–Guignol. When Yvonne announces that she and her husband, famous pianist Stephen Orlac, are moving to England, Dr. Gogol experiences his first crisis. “I, a poor peasant, have conquered science. Why can’t I conquer love?”

This question is answered when Yvonne returns, begging Dr. Gogol to save her husband’s hands, crushed in a train crash. Amputation is the only possibility… but, hold on – could the hands of a recently executed knife-throwing murderer be transplanted on to Orlac? What could possibly go wrong? With a score by Dimitri Tiomkin, in Mad Love, scientific knowledge is truly a double-edged scalpel.

Mad Love is a remake of the 1924 Austrian silent horror movie, Orlacs Hände (The Hands of Orlac), itself based on Maurice Renard’s body-horror novel of 1920, Les Mains d’Orlac. Renard was inspired by the work of Alexis Carrel, a Nobel Prize-winning French surgeon known for his suturing techniques. Renard’s organ-transplanting and skin-grafting surgeon became Mad Love’s Dr. Gogol.

Mad Love is a remake of the 1924 Austrian silent horror movie, Orlacs Hände (The Hands of Orlac), itself based on Maurice Renard’s body-horror novel of 1920, Les Mains d’Orlac. Renard was inspired by the work of Alexis Carrel, a Nobel Prize-winning French surgeon known for his suturing techniques. Renard’s organ-transplanting and skin-grafting surgeon became Mad Love’s Dr. Gogol.

Renaud’s novel inspired at least four films in which a mad doctor turns a pianist into a murderer by transplanting the hands of an executed prisoner – in one case a knife thrower; in another, a strangler. Sergio Mims, film critic, historian, and co-founder of Chicago’s Black Harvest Film Festival, points out that for at least the first half of the 20th century, the idea of transplanting human organs or entire body parts was more science fiction than science fact.

The possible reality of such an operation, with no real knowledge of the outcome, created unease in the public. Add in doubts as to the moral character of someone who would use their knowledge to perform such ungodly procedures, and you’ve got yourself a horror story. Two more films are based on Renard’s novel: The Hands of Orlac (aka Hands of the Strangler,) starring Mel Ferrer, Christopher Lee, and Donald Pleasance, is a 1960 horror film produced in French and English versions. Hands of a Stranger, released in 1962, perhaps is most notable for the appearance of Sally Kellerman, in her second film, in the minor role of the benignly named Sue.

Peter Lorre in The Beast with Five Fingers (Gif embedded from bigcomicpage.com)

For 1946’s The Beast with Five Fingers, Peter Lorre’s singular acting abilities again are called into service; this time as both a practitioner of the occult arts and the creepy secretary to former virtuoso pianist Frances Ingram, whose right side is paralyzed following a stroke. Never mind the paralyzed pianist’s disembodied left hand with a life of its own… and death in its fingers. What matters most (for us anyway) is the score by Max Steiner, as well as the “Chaconne” from Johann Sebastian Bach’s Violin Partita in D minor, heard throughout the film in a modified version of Brahms’ transcription for left hand, performed by pianist Victor Aller. It’s Aller’s disembodied hand that we see at the piano, an effective trick before the days of CGI. Aller sat under the piano, with his arm wrapped in black velvet.

Robert Alda played a friend of the paralyzed pianist in The Beast with Five Fingers. It was Robert’s son, Alan, who portrayed an unsuccessful pianist turned music critic, Myles Clarkson, in The Mephisto Waltz, released in 1971, the year before a TV show called M*A*S*H debuted.

This horror-thriller with a score by Jerry Goldsmith takes its name from the Mephisto Waltzes of Franz Liszt. Alda/Clarkson is a pianist whose unsatisfying career forces him to turn (The horror!! The horror!!) to music criticism. Curd Jürgens plays Duncan Ely, a world-renowned virtuoso pianist who is dying from leukemia. Oh, and, Ely is also a Satanist, as is his daughter Roxanne (Barbara Parkins). A Satanic ritual transfers the consciousness of the dying virtuoso Ely into the body of (mere) critic Clarkson. Slowly, Clarkson’s piano technique improves, to the point where he is now the world’s greatest virtuoso. His wife Paula (Jacqueline Bisset) strikes her own Faustian bargain, inhabiting Roxanne’s body with her consciousness and disposing of her former shell. And so Duncan’s soul in Myles’s body and Paula’s in Roxanne’s live satanically ever after.

The relationship between science fact and science fiction has always been something of a bridge, with inspiration flowing in both directions. Whether it’s Leonardo da Vinci’s revolutionary plans for flying machines and concentrated solar power, Jules Verne’s Extraordinary Voyages series, or Star Trek’s hands-free, voice-activated communicators and phasers, it’s our imagination that keeps us in fear or helps us conquer it. Just as the unimaginable becomes the near-at-hand, so too do we brush aside the veils of superstition and fear. “Through the hand, human culture waves away animal nature,” reflects Raymond Tallis in The hand: a philosophical inquiry into human being. Well, mostly. The ancient and universal nightmares still persist today, even, and perhaps especially, when we should know better.