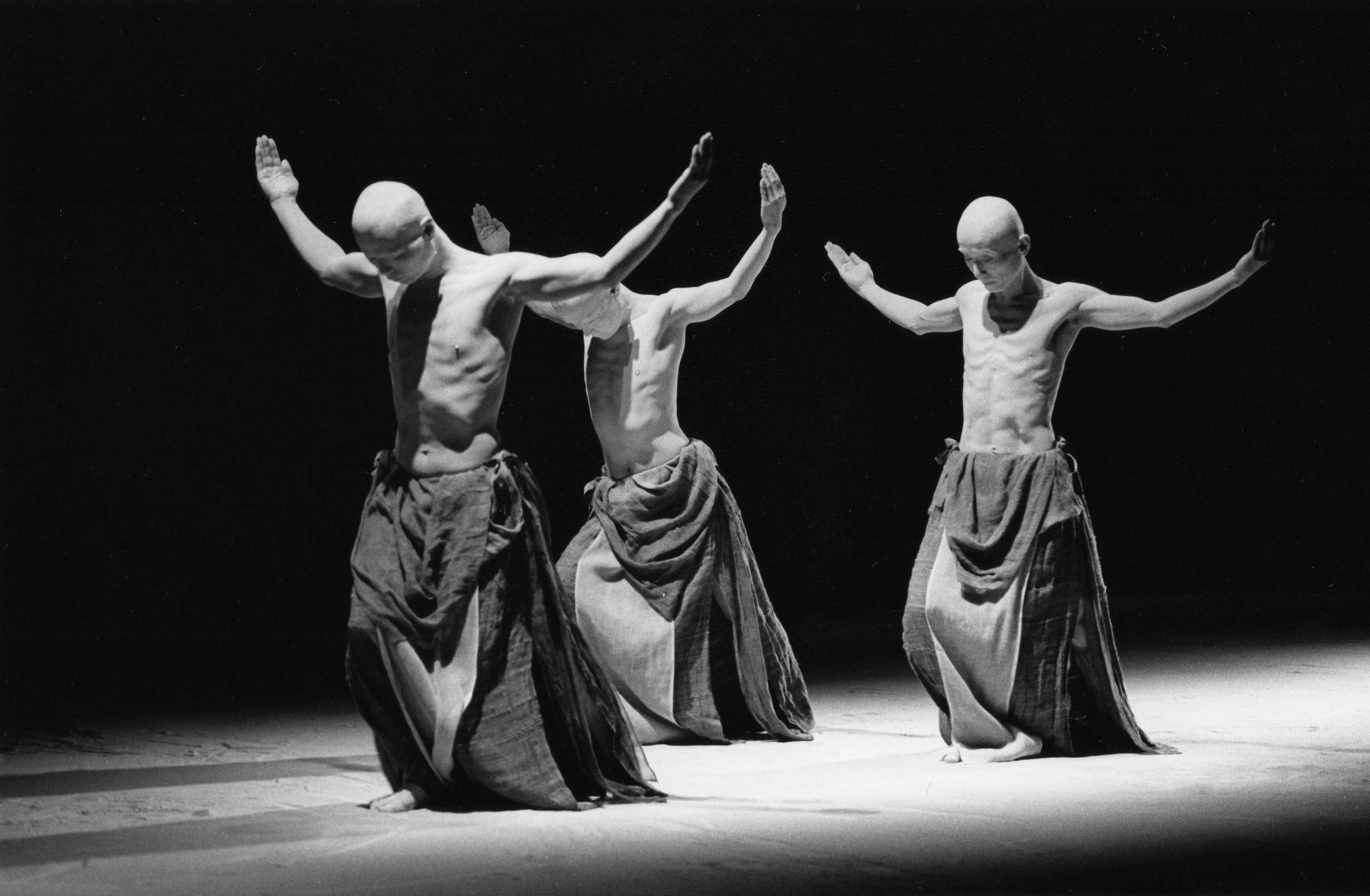

One of the most unique styles of dance today is undoubtedly butoh. I spoke with dancer and choreographer Ushio Amagatsu as he tours across North America with his company, Sankai Juku. The New York Times called Sankai Juku, “One of the most original and startling dance theater groups to be seen.”

One of the most unique styles of dance today is undoubtedly butoh. I spoke with dancer and choreographer Ushio Amagatsu as he tours across North America with his company, Sankai Juku. The New York Times called Sankai Juku, “One of the most original and startling dance theater groups to be seen.”

Read our conversation to learn more about butoh, Amagatsu’s own personal style, and his latest work, UMUSUNA: Memories Before History.

WFMT: For someone who has never encountered butoh before, can you describe this unique style of dance?

Ushio Amagatsu: I basically think that Butoh is a dialogue with gravity. That is not repulsion to gravity, but is more close to conformity with gravity. Therefore, a little careful way of corresponding with gravity is necessary. In this view, some people may say our dance is a slow motion, but it’s not. It is a result of careful correspondence with gravity.

WFMT: For those who are unfamiliar with classical Japanese art forms, can you describe what, if any, traditional art forms butoh draws upon?

Amagatsu: I get impressions from all the other genres. For example, from literature, poem, philosophy, painting, music of course. I have not studied fine arts specifically. As I have Japanese artist friends who are painters and sculptors, the dialogue with them enriches me as well as their pieces. Basically not from others’ dance, but from all the other physical things.

But the important thing is to keep me void. Empty. For example, think about a glass. If it’s not empty, nothing can come in. So, I try myself empty first. Pouring something comes later.

WFMT: Are there ways in which butoh arose in the middle of the 20th century as a reaction to changing attitudes and ideas in post-World War II Japan?

Amagatsu: My generation is different from Butoh artists such as Tatsumi Hijikata or Kazuo Ono, and consequently my experiences are different from those first- generation Butoh artists. I guess that experiences of World War II influenced them in a sense, and that their creations might have stemmed deeply from an “identity as Japanese.” Meanwhile, in my case, after the first Europe tour in 1980, by experiencing the different cultures and the universality beyond culture as an everyday shower, those differences and the universality became my foundation in creation.

WFMT: Now that butoh has flourished for several decades, how would you describe butoh today?

My curiosity and interests on how people stand, walk, and move . . . never run out. The process of people come to stand is common beyond cultures or human races. And people will repeat it for over millions of years from now on, too. The relationship of people and nature (environment) there, too, are interesting for me.

WFMT: Can you describe your own process for creating new work?

Amagatsu: When I begin working with the dancers on a new piece, on our first day together I start with a short lecture on what I want to do in the new piece. And once I have communicated in that way my general idea, then we begin working on the actual physical movements, which I call “Trial #1.” The Sankai Juku dancers are of course thoroughly familiar with this process now, so when I say, “OK, let’s start Trial #1,” they know what it means. And they know that then it changes and develops naturally from there to #2 and #3. That process is repeated over and over with concentration by the dancers in the studio until a consensus is reached, or until I myself am convinced that something is right. There are times when everything goes well from the start and a five minute scene may be worked out to successfully in the course of one day in the studio, but at other time we may spend a whole day working and not even one minute of a scene is worked up to satisfaction. Still, the Sankai Juku must have the patience and the concentration to keep focused internally and keep working like that in a studio with no mirrors or music.

Amagatsu: Umusuna is an ancient Japanese word that means a place of one’s birth. When I apply this word to the whole human being, the earth itself becomes Umusuna. I believe that the relationship between the place of birth and people is always deeply affected by a certain natural element, and I don’t think this relationship doesn’t change at present, and in the future as well, as it didn’t change in the past. This is my motif.

WFMT: Can you describe some of the physical production elements (costumes, set elements, lighting) in UMUSUNA?

Amagatsu: I design the set and the costumes in advance. I begin with my memos and designs. First, the image of the new work is vague, but using these memos and designs, I drop off the unnecessary parts of them, and I narrow it down. This is the process of my creation.

I used sand in ”UNETSU”(1986), for the first time, in which the set consisted of sand and water.

If we assume that water symbolizes life, then, sand may symbolize the final stage of it. Water spreads horizontally, and sand accumulates and it symbolizes the time that has passed. In my recent works, I spread a thin layer of sands on the floor. The footprints of dancers will make a relief of their movements of one hour and a half.

As for music, it is created specifically for the piece. I work with three composers. The way I ask for music varies from each composer. For Mr Takashi Kako, I choose one of his original music compositions (piano) and ask him to arrange it for my work, using other instruments. In this case, since his music exists already, it could make a part of a text for my piece. In other cases with two composers, I ask them (Yoichiro Yoshikawa and Yas-Kaz) to compose in parallel with my choreographic process. Therefore, in this case, music comes only when the choreography is almost finished in a later process of creating a piece.

To learn more about Ushio Amagatsu and Sanaki Juku, visit the company’s website.