Christine Rocas and members of the Joffrey Ballet perform Pastor’s Romeo and Juliet (Photo: Cheryl Mann)

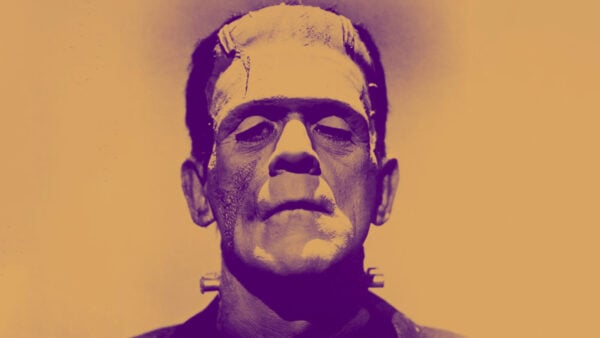

When you think of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, you likely think of the two titular lovers and their tragic romance. But Sergei Prokofiev put politics at the center of his Shakespeare-inspired ballet, Romeo and Juliet, and got wrapped up in Soviet-era politics himself in composing it.

In 1935, Prokofiev accepted a commission to create a new ballet for the Bolshoi Theatre. When he finished the score to Romeo and Juliet, however, Soviet officials were shocked. Though Shakespeare’s play was first published as The Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet, Prokofiev’s ballet had a happy ending.

In the first version of the ballet, Romeo believes Juliet is dead, though Friar Lawrence explains that she has merely taken a sleeping potion. Juliet awakens and is reunited with Romeo. The two literally dance off into eternal happiness.

Why did Prokofiev change the ending to one of the best-known stories of all time?

He explained, “living people can dance, the dead cannot.” The director, Sergei Radlov, clarified this decision a bit more, saying the story is “about the struggle for the right to love by young, strong, and progressive people battling against feudal traditions and feudal outlooks on marriage and family.”

Galina Ulanova and Yuri Zhdanov in the Kirov’s Romeo and Juliet (Photo: RIA Novosti archive, image #11591 /Umnov/ CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Prokofiev’s progressive re-telling may have resonated with audiences of the time. Ultimately, Bolshoi’s chairman, Platon Kershentsev, was suspicious that the composer had been influenced by anti-populist sentiments during his time outside of the Soviet Union and delayed producing it. Though Romeo and Juliet was scheduled for the 1937 season, the administration did not think it was fitting to perform the work during the 20th anniversary of the revolution. Romeo and Juliet was shelved until 1940, five years after it was completed, when the Kirov demanded substantial changes to both the orchestration and the dramatic scenario, including the ending.

Music from the original ending, which totals approximately fifteen minutes, was recently discovered in the archives. Mark Morris Dance Group performed the ballet with this newly-found material in 2008 at the Bard Summerscape festival, giving Prokofiev’s original work its official world premiere almost 75 years after he composed it.

The same year, choreographer Krzysztof Pastor premiered his staging of Romeo and Juliet with the Scottish Ballet at the Edinburgh Festival Theatre. Pastor keeps politics at the center of the story, though unlike Morris, he used the composer’s revised, tragic ending.

The Joffrey Ballet brought Pastor’s production to Chicago for its US premiere in 2014, and opens its 2016-17 season Thursday, October 13 with a revival of it at the Auditorium Theater. Ashley Wheater, the company’s artistic director, said, “There are so many different ideas to portray in this story, and many different ways the audience could leave the theater after seeing Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet.”

“Will we ever learn about the horror and destruction that war will bring? It seems like we’re never going to. It’s a tragedy. Two young people die, and we pick their bodies up, and both families continue to hold their hatred.”

Pastor has updated his version to the 20th century, placing each act of the ballet into three recent eras of Italian political history: the rise of fascism in the 1930s; the rise of the Red Brigade in the 1950s; and Berlusconi’s rise to power in the 1990s.

![The Joffrey Ballet performs Pastor's "Romeo & Juliet" ft. Rory Hohenstein & Christine Rocas [Photo: Cheryl Mann]](https://www.wfmt.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Joffrey-Romeo-Juliet-ft.-Rory-Hohenstein-Christine-Rocas-8-Photo-by-Cheryl-Mann-e1665810031519.jpg)

Rory Hohenstein and Christine Rocas of the Joffrey Ballet performs Pastor’s Romeo and Juliet (Photo: Cheryl Mann)

“Pastor is Polish, and he has lived in an area of conflict,” Wheater said. “What really impacted him was the story of what happened in Sarajevo in the ’90s of a young couple from different religions, and different families, and who were shot dead on a bridge when trying to escape, and they were left there for four days before people went to pick them up.” This tragic love tale was the subject of a documentary, Romeo and Juliet in Sarajevo, which you can sample in part below:

“There’s no right or wrong time for love,” Wheater said. “This work forces us to ask ourselves, ‘Is it better to die than keep living in conflict?’ When people think of ballet, they romanticize it and think it’s all very pretty. But I think it’s refreshing to see a production that can use the body to explore suffering.

“The last time we did this production, you could hear that people were really upset by it. And yet, there is absolutely beautiful choreography — it’s absolutely stunning.”