Throughout music history, there have been many well-known friendships among composers. J.S. Bach and Telemann were so close that Telemann became the godfather to one of Bach’s sons, Carl Philipp Emmanuel. The friendship between Haydn and Mozart is so famous there’s an entire Wikipedia page describing it. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s friendship with Modest Mussorgsky was immortalized by Venedict Yerofeyev’s poem Moscow-Petushki, which depicts Rimsky-Korsakov waking up his (drunk) buddy in a ditch.

The six pairs of pals below are only a few of music’s most dynamic duos. Whether bosom buddies like Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams or something more complicated like Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler, there’s no doubt that these composers enjoyed genuine friendships that would influence their personal and professional lives. Don’t forget to tell us your favorite musical friendships in the comments!

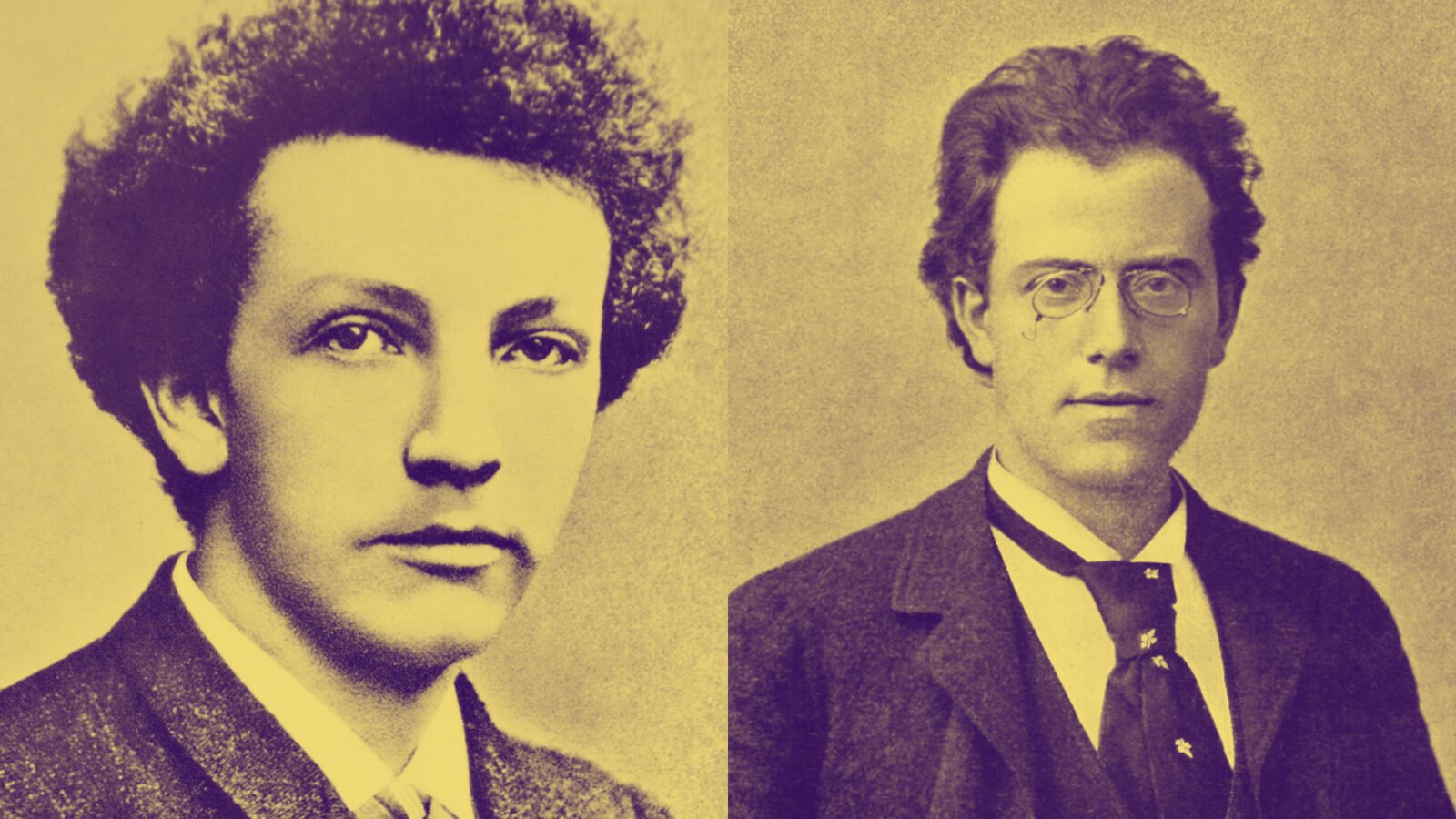

Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler

Strauss and Mahler did not exactly have a warm, fuzzy friendship, but they did share a strong professional and personal respect for one another. In many ways, they were also quite similar. Both were better known in life as conductors, not composers, and were seen as outsiders in Vienna, which was all but homogenous at the time. Strauss was ridiculed for his Bavarian accent, and Mahler found that converting to Catholicism was not enough to silence mutterings about his Bohemian Jewish background.

Strauss and Mahler did not exactly have a warm, fuzzy friendship, but they did share a strong professional and personal respect for one another. In many ways, they were also quite similar. Both were better known in life as conductors, not composers, and were seen as outsiders in Vienna, which was all but homogenous at the time. Strauss was ridiculed for his Bavarian accent, and Mahler found that converting to Catholicism was not enough to silence mutterings about his Bohemian Jewish background.

The two first met in Leipzig in 1887, around the time both were rising to prominence as sensations behind the podium. But for all these similarities, in personality and appearance, the two were polar opposites. Strauss was day to Mahler’s night: He was lanky, pale, level-headed, and easygoing, while the short, dark Mahler was hopelessly mercurial and often solitary.

Alma Mahler recounts evenings spent with the Strausses, during which she and Pauline de Ahna would listen to their husbands argue in the adjoining room. But such jousting matches were in good spirit. As Alma recalls, “They enjoyed talking to one another, as they were never of one mind.” Being of such different minds, it is unsurprising that the men’s relationship suffered frequent miscommunications, with Mahler imagining slights from a very clueless Strauss on more than one occasion.

Luckily, where words failed them, both men connected through the same musical language, namely the thick orchestration and expanded instrumental forces of the late Romantic era. Strauss and Mahler used these tools to build towering, all-encompassing works, and they greatly admired each other’s output. As director of the Vienna State Opera, Mahler championed Strauss’s operas, defending the racy and graphic Salome when censors barred it from performance. Strauss returned the favor by programming Mahler’s symphonies wherever he went.

Of his friend, who was to outlive him by more than three decades, Mahler said: “Strauss and I tunnel from opposite sides of the mountain. One day we shall meet.”

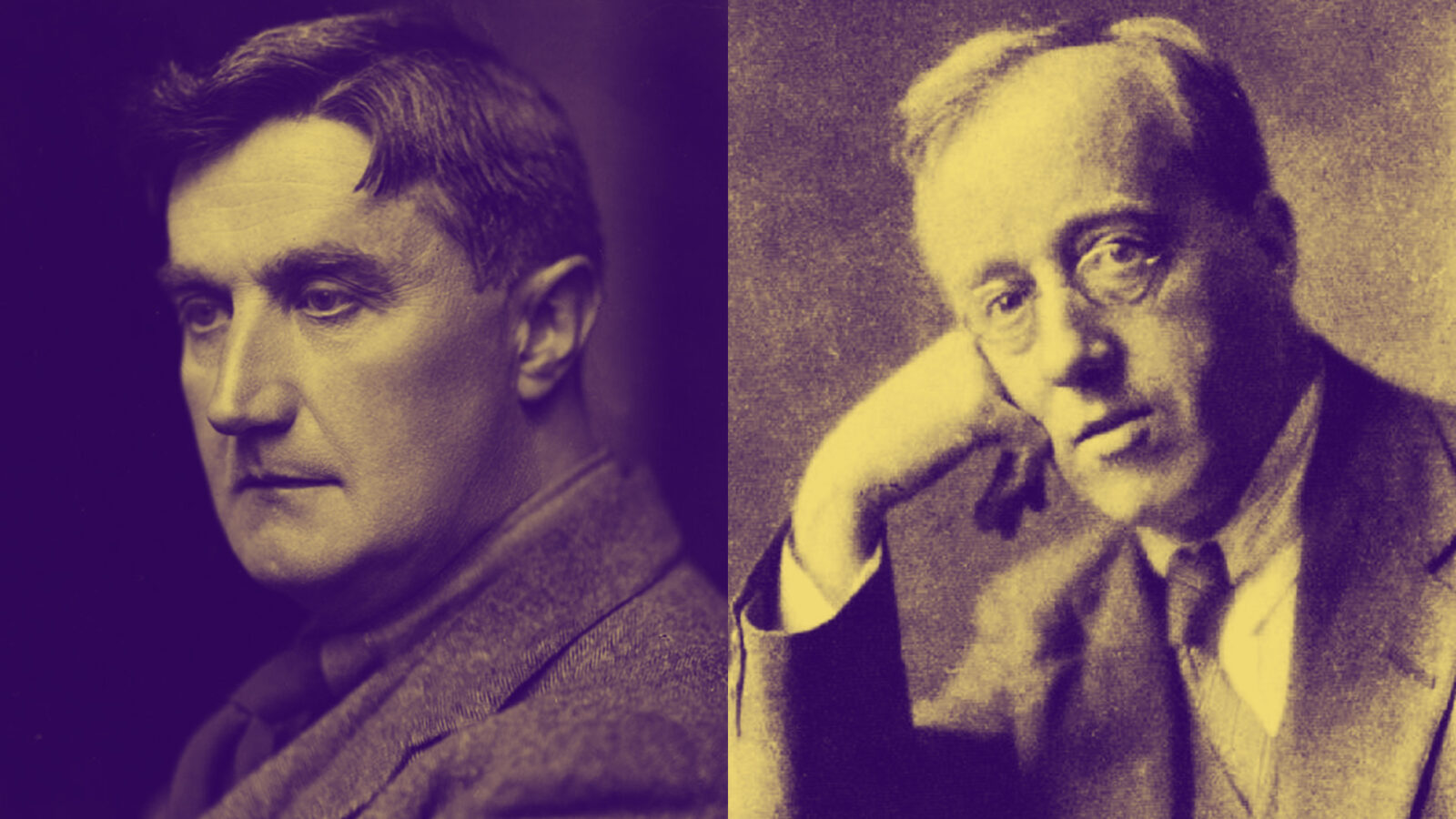

Ralph Vaughan Williams and Gustav Holst

In 1890, Vaughan Williams and Holst met as students at the Royal College of Music. They became fast friends, playing their student pieces for one another. It was the beginning of a long and fruitful friendship that lasted more than 40 years.

In 1890, Vaughan Williams and Holst met as students at the Royal College of Music. They became fast friends, playing their student pieces for one another. It was the beginning of a long and fruitful friendship that lasted more than 40 years.

Of the two, Vaughan Williams spilled more ink about their friendship. He wrote an entry about his friend for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography in 1949 and was always quick to publicly give Holst credit where credit was due. Vaughan Williams called him “the greatest influence on my music,” and dedicated his Mass in G minor to him.

When it came to each other’s music, both believed that imitation was the sincerest form of flattery. Vaughan Williams described their mutual borrowing in 1954:

“Holst used to say that he cribbed from me: I could never perceive this myself. But I could give you chapter and verse of the places where I have borrowed from him… Composers whose thoughts run on parallel lines, especially if they are master and pupil, or even great friends, will often find that the lines converge and become identical. This, I hope will explain my borrowing from Holst, and I am indeed, not ashamed, but proud of it.”

That being said, Holst and Vaughan Williams’s thought-lines did not converge so often that they were always in creative agreement. They regularly scrutinized each other’s work, giving ample feedback. On one occasion, when Holst tried to write his own libretto for an opera, Vaughan Williams even suggested that he essentially rewrite the whole thing!

Neither man was insulted by the other’s criticisms – on the contrary, they embraced them. In fact, when Holst died in May 1934, Vaughan Williams found himself at a loss without his friend to provide constructive feedback. As he wrote to Holst’s wife and widow that year, “My only thought is now which ever way I turn, what are we to do without him—everything seems to have turned back to him–what would Gustav think or advise or do.”

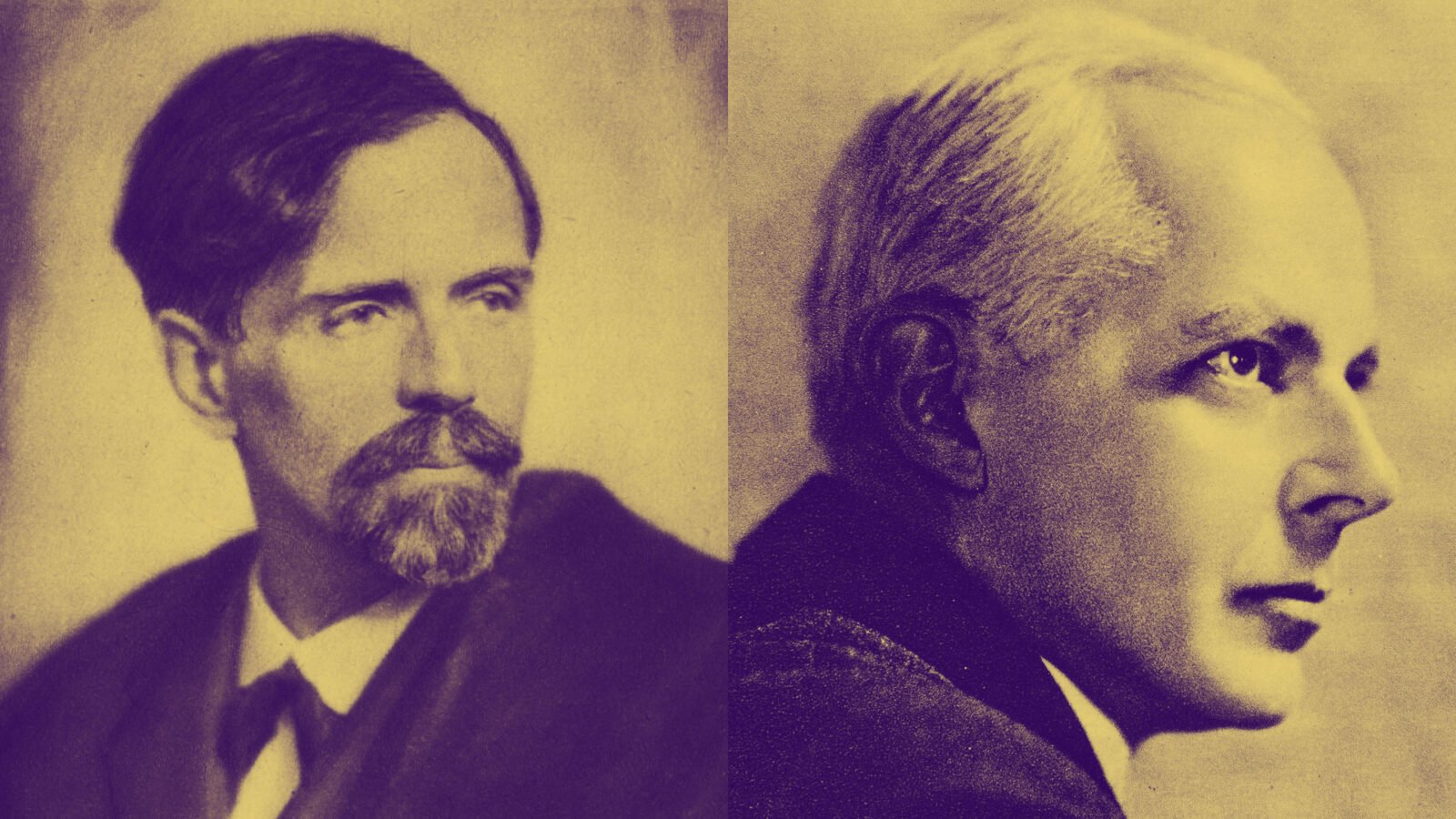

Zoltán Kodály and Béla Bartók

Born only a year apart, Kodály and Bartók are yet another sterling example of like-minded contemporaries. Aside from a shared interest in composition, they were both passionate about ethnomusicology and music education.

Born only a year apart, Kodály and Bartók are yet another sterling example of like-minded contemporaries. Aside from a shared interest in composition, they were both passionate about ethnomusicology and music education.

Kodály and Bartók became close when they teamed up to document Hungarian folk music on phonograph cylinders. By that time, Kodály had already written a thesis on the subject. Following their project, they co-published a set of Hungarian folk songs for voice and piano in 1906. Their work together made such an impression on the 25-year-old Bartók that he was compelled to explore the folk music of nations outside Hungary.

But the most lasting effect of this experience was its profound influence on both men’s compositional style. Folk music influenced Kodály’s compositions by lending them unique colors and a more tuneful, Romantic approach to composition. The more avant-garde Bartók, on the other hand, relished the exotic modalities of Hungarian music and often adopted a less tuneful and more angular approach to incorporating folk elements into his own music.

After both being appointed professors at the Academy of Music in Budapest, the two embarked on another joint venture in 1911, founding the New Hungarian Music Society. Hungary’s tense interwar period led to the suspension of both men from their Academy posts in 1919 for political reasons.

Kodály became an outspoken advocate for music education in his native Hungary. He pioneered the Kodály Method, which stresses the importance of early musical immersion and aural training. The method is still popular today and influenced a number of other musical training schools.

Both men were lifelong champions of each other’s music, and before his death in 1945, Bartók managed to record some of his friend’s pieces on the piano.

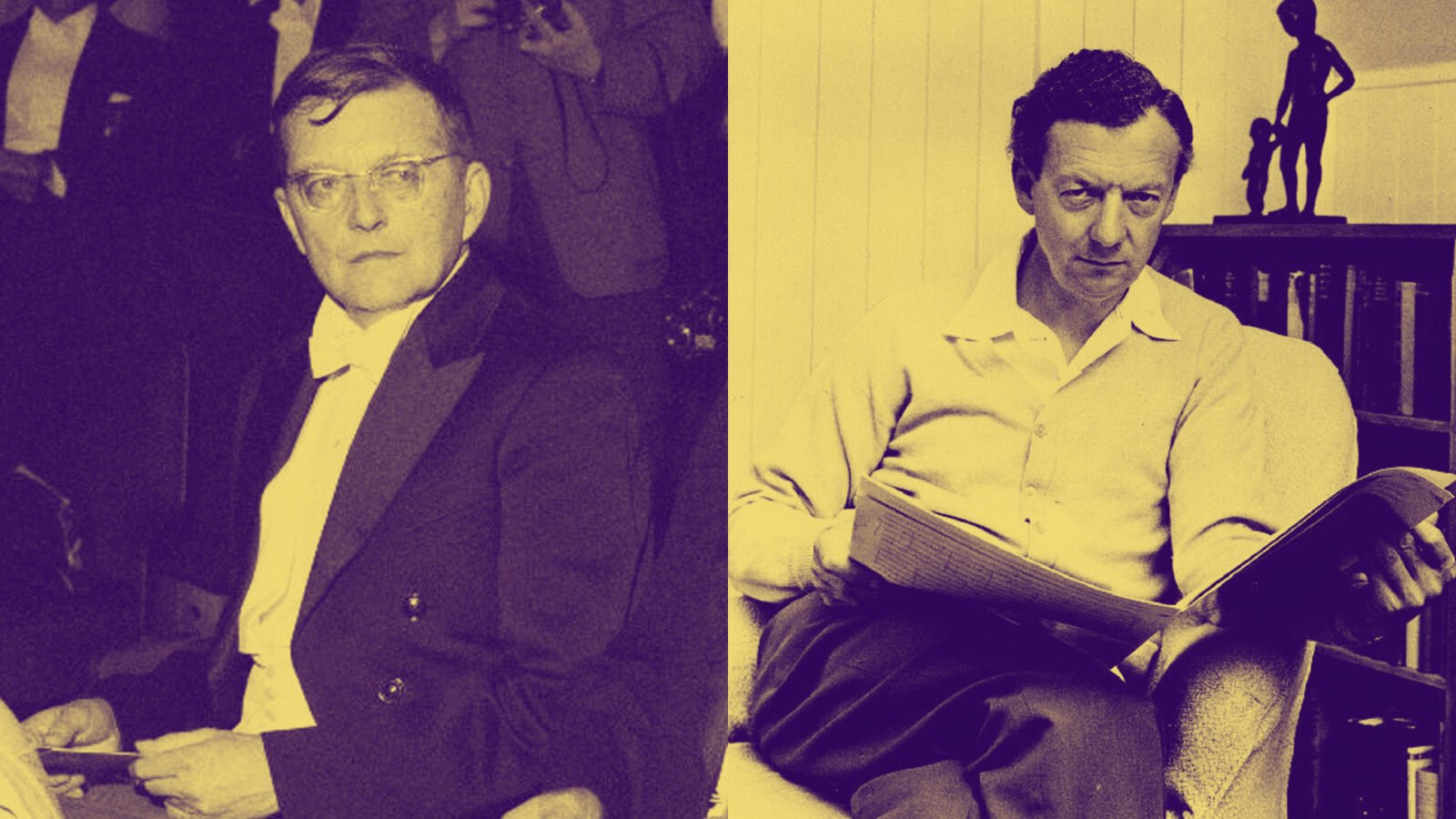

Dmitri Shostakovich and Benjamin Britten

The 22-year-old Benjamin Britten was first introduced to Dmitri Shostakovich’s music when he attended a 1935 performance of Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. Although Shostakovich himself wasn’t much older than Britten, the younger composer was extremely impressed by what he heard and looked to the work as inspiration for his own operas.

The 22-year-old Benjamin Britten was first introduced to Dmitri Shostakovich’s music when he attended a 1935 performance of Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. Although Shostakovich himself wasn’t much older than Britten, the younger composer was extremely impressed by what he heard and looked to the work as inspiration for his own operas.

It would be 25 years before the two composers met face-to-face. Both men were seated in the same box at the British premiere of Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 1, performed by Mstislav Rostropovich. During the concert, Shostakovich noticed that Britten “was bobbing up and down like a schoolboy, even nudging me with happiness at the music.” Shostakovich introduced Britten to Rostropovich after the performance, beginning not one, but two lifelong friendships.

Shostakovich and Britten continued to support each other’s work throughout the remainder of their careers. Both counted Gustav Mahler among their greatest influences and recognized in the other’s music a similar purity of expression and singularity of sound. Shostakovich was particularly taken with Britten’s War Requiem, and once even praised the British composer as a representation of everything right in modern music. As he elaborated in an interview, he admired Britten’s music for its “strength and sincerity… its surface simplicity and the intensity of the music’s emotional effect.” The composers also dedicated works to one another: Shostakovich his Symphony No. 14, and Britten his opera The Prodigal Son.

Shostakovich visited Britten’s Aldeburgh Festival once, and Britten returned the favor with several visits to the Soviet Union. Britten and his partner Peter Pears would often stay with the Shostakovich family. The language barrier, it seems, was never an impediment to their friendship, which was unerring throughout the years. Shostakovich suffered a string of heart attacks in 1966, but not even poor health could keep him from attending his friend’s song recital in Moscow the same year. The two men died within a year of one another.

Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein

When Copland first met Bernstein at a New York dance recital, Copland was lauded as one of America’s greatest living composers and Bernstein was a 19-year-old junior at Harvard. As it happened, Copland’s Piano Variations was one of young Bernstein’s favorite works. That night, Bernstein played the Variations for Copland, who was so impressed that he remarked, “I wish I could play it like that.”

When Copland first met Bernstein at a New York dance recital, Copland was lauded as one of America’s greatest living composers and Bernstein was a 19-year-old junior at Harvard. As it happened, Copland’s Piano Variations was one of young Bernstein’s favorite works. That night, Bernstein played the Variations for Copland, who was so impressed that he remarked, “I wish I could play it like that.”

After another chance meeting a few years later, the two started corresponding, during which Bernstein asked if he could study composition with Copland. Though Bernstein never formally became his protégé, Copland continually offered his friend feedback. During this period, the two were closest. “There can never be one closer to me than you are,” Bernstein tenderly wrote to Copland in 1942.

Bernstein certainly did owe a lot to his friend: it was actually Copland who helped kick-start Bernstein’s conducting career. He encouraged him to study conducting with Fritz Reiner at Curtis (in which Bernstein was reportedly the only student to ever receive an A). Copland also recommended that Bernstein get to know the work of conductor Serge Koussevitsky, then at the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Copland did more than anyone else to promote Bernstein the conductor but was generally more ambivalent about Bernstein the composer. As Bernstein’s star rose, he felt comfortable criticizing his mentor’s music. Their frank criticism of each other’s work was an occasional source of tension.

The same went for their personality differences. The effusive and extroverted Bernstein complained that Copland “masks his feelings.” Other accounts prove that Bernstein was not alone in observing that “there’s a great deal going on inside [Copland] that doesn’t come out, even with his best friends.”

But no amount of difference or disagreement weakened the men’s friendship, and they remained close until the end. Despite their 18-year age difference, the men died the same year. In fact, the older Copland outlived his friend by nearly two months.

Lou Harrison and John Cage

Contemporary composers Harrison and Cage both grew up in urban California – Harrison in the San Francisco Bay Area, and Cage in Los Angeles. They met in San Francisco in the late ’30s while working with dance companies and bonded over their interest in percussive writing. During this period, they combed curiosity shops and car graveyards for objects that could be used for their compositions.

After giving percussion concerts together in 1940, they co-composed a percussion quartet, Double Music, in 1941. They composed their contributions separately, with Cage taking parts 1 and 3 and Harrison parts 2 and 4. As Harrison recalls, when the parts came together, they “never changed a note.”

Harrison painted a fond picture of his friend after his death: “We were very close friends, and visited almost daily… John was a very entertaining man. We got along very well. In fact, I never had an altercation with John.”

One touching testament to their friendship is a heartfelt poem Harrison wrote in 1977, for Cage’s 65th birthday:

You, John, are a loved, romantic man –

So multiple of image that Each

Designs another one about you

Who concieves [sic] you in his heart or mind

And so adds facet to your being

Such that often All seems equally

Reflected, and that gigantic You,

That high chance-shimmering agregate [sic]

Gleams to all like the Sun Resplendent.