Though we tend to remember our favorite composers for their music first and foremost, many of them were virtuosic in more ways than one. When abbess Hildegard von Bingen wasn’t busy composing one of the earliest known operas in history, she was busy brewing beer. When Sergei Prokofiev wasn’t planning one of his next musical masterpieces, he was often trying to improve his chess game. Discover more about your favorite composers and their hidden talents below. Some may surprise you.

Though we tend to remember our favorite composers for their music first and foremost, many of them were virtuosic in more ways than one. When abbess Hildegard von Bingen wasn’t busy composing one of the earliest known operas in history, she was busy brewing beer. When Sergei Prokofiev wasn’t planning one of his next musical masterpieces, he was often trying to improve his chess game. Discover more about your favorite composers and their hidden talents below. Some may surprise you.

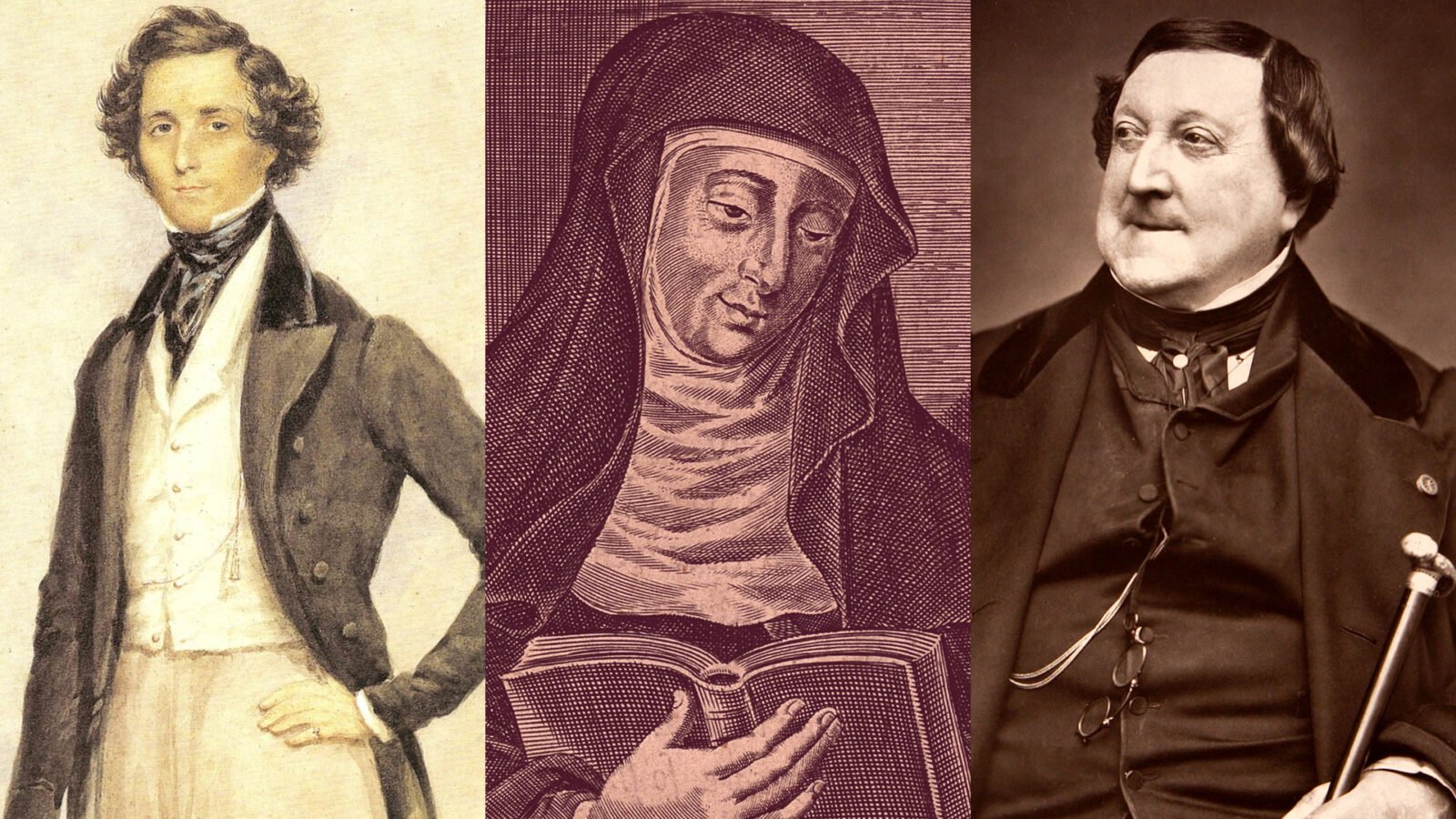

Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179)

Brewer

Hildegard was a multihyphenate if there ever was one. Besides being an abbess, writer, philosopher, and scientist, she was a pioneering composer. She left behind scores of liturgical songs and a musical morality play, Ordo Virtutum—essentially, a proto-opera. But Hildegard had a lesser-known talent: she used her scientific know-how to unlock the secret to tastier, longer-lasting beer. How? She was the first person to record using hops in beer. “[Hops], when put in beer, stops putrification and lends longer durability,” she wrote in her Physica Sacra (translation via The Beer Devotional by Jess Lebow). She also mentions that hops increase melancholy or “black bile.” She was right: hops can indeed depress the nervous system and make you sleepy.

Hildegard was a multihyphenate if there ever was one. Besides being an abbess, writer, philosopher, and scientist, she was a pioneering composer. She left behind scores of liturgical songs and a musical morality play, Ordo Virtutum—essentially, a proto-opera. But Hildegard had a lesser-known talent: she used her scientific know-how to unlock the secret to tastier, longer-lasting beer. How? She was the first person to record using hops in beer. “[Hops], when put in beer, stops putrification and lends longer durability,” she wrote in her Physica Sacra (translation via The Beer Devotional by Jess Lebow). She also mentions that hops increase melancholy or “black bile.” She was right: hops can indeed depress the nervous system and make you sleepy.

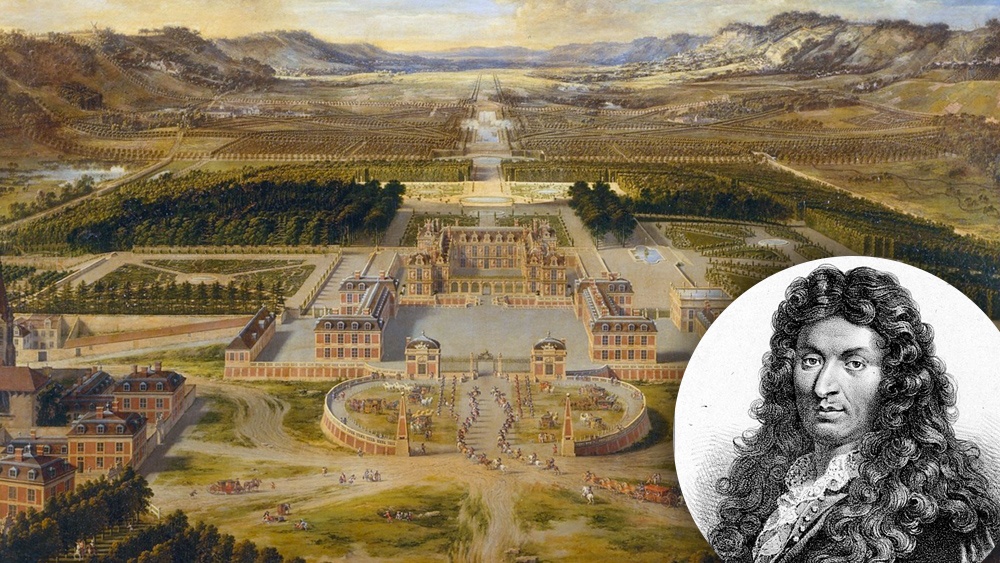

Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632–1687)

Dancer

Lully’s big break came when he was hired by King Louis XIV to compose ballets for the royal court. However, he entered the court not as a composer, but as a dancer himself. The young king, just five when he took the throne, was keenly interested in the performing arts and found a kindred spirit in Lully, who had displayed prodigious talent in both music and dance from an early age. In fact, many of the ballets Lully composed actually featured him and the King as dancers, like 1653’s Ballet de la nuit. As director of the Académie Royale de Musique from 1672 to 1687, Lully oversaw the company’s dance school, which still exists as part of the Paris Opera Ballet. Lully also did his part to help break the glass ceiling in ballet, hiring Madamoiselle de Lafontaine, the first female ballerina, for his ballet Le triomphe de l’amour.

Lully’s big break came when he was hired by King Louis XIV to compose ballets for the royal court. However, he entered the court not as a composer, but as a dancer himself. The young king, just five when he took the throne, was keenly interested in the performing arts and found a kindred spirit in Lully, who had displayed prodigious talent in both music and dance from an early age. In fact, many of the ballets Lully composed actually featured him and the King as dancers, like 1653’s Ballet de la nuit. As director of the Académie Royale de Musique from 1672 to 1687, Lully oversaw the company’s dance school, which still exists as part of the Paris Opera Ballet. Lully also did his part to help break the glass ceiling in ballet, hiring Madamoiselle de Lafontaine, the first female ballerina, for his ballet Le triomphe de l’amour.

Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745–1799)

Fencer

Chevalier de Saint-Georges was a writer, revolutionary, swimmer, runner, war hero, marksman—pretty much everything Saint-Georges tried, he mastered. He supposedly came to music rather late in life, and shocked the public when, to top it all off, he revealed himself as a gifted violinist, conductor, and composer. It, after all, knew Saint-Georges primarily as Europe’s greatest fencer—the equivalent of NBA star Stephen Curry plopping down at a piano to spin out a Rachmaninoff concerto, unprompted. Saint-Georges proved his fencing prowess many times over, most sensationally in 1765: while still a student, he beat a fencing master in Rouen who’d mocked him with racist jibes. (You can read the full story in Gabriel Banat’s biography of the composer.)

Chevalier de Saint-Georges was a writer, revolutionary, swimmer, runner, war hero, marksman—pretty much everything Saint-Georges tried, he mastered. He supposedly came to music rather late in life, and shocked the public when, to top it all off, he revealed himself as a gifted violinist, conductor, and composer. It, after all, knew Saint-Georges primarily as Europe’s greatest fencer—the equivalent of NBA star Stephen Curry plopping down at a piano to spin out a Rachmaninoff concerto, unprompted. Saint-Georges proved his fencing prowess many times over, most sensationally in 1765: while still a student, he beat a fencing master in Rouen who’d mocked him with racist jibes. (You can read the full story in Gabriel Banat’s biography of the composer.)

Gioachino Rossini (1792–1868)

Gourmand and amateur chef

Rossini enjoyed food that was as extravagant as the music he composed for his florid bel canto operas. Famous chefs named several dishes after the composer, including the famous Tournedos Rossini. There are competing origin stories for how the dish was named, many of which showcase Rossini’s culinary knowledge. One account in Larousse Gastronomique claims that Rossini invented it on the spot while ordering at a restaurant; to avoid inquiry, the head waiter had to serve the decadent dish behind the backs of the other diners. In another version, Rossini tried to play maestro to a respected Parisian chef. According to the Academia Italiana Gastronomia, Rossini repeatedly interrupted the chef’s preparation of the dish to comment and complain. The chef finally told Rossini to bug off, to which Rossini replied, “Et alors, tournez le dos”—”Then turn your back!”

Rossini enjoyed food that was as extravagant as the music he composed for his florid bel canto operas. Famous chefs named several dishes after the composer, including the famous Tournedos Rossini. There are competing origin stories for how the dish was named, many of which showcase Rossini’s culinary knowledge. One account in Larousse Gastronomique claims that Rossini invented it on the spot while ordering at a restaurant; to avoid inquiry, the head waiter had to serve the decadent dish behind the backs of the other diners. In another version, Rossini tried to play maestro to a respected Parisian chef. According to the Academia Italiana Gastronomia, Rossini repeatedly interrupted the chef’s preparation of the dish to comment and complain. The chef finally told Rossini to bug off, to which Rossini replied, “Et alors, tournez le dos”—”Then turn your back!”

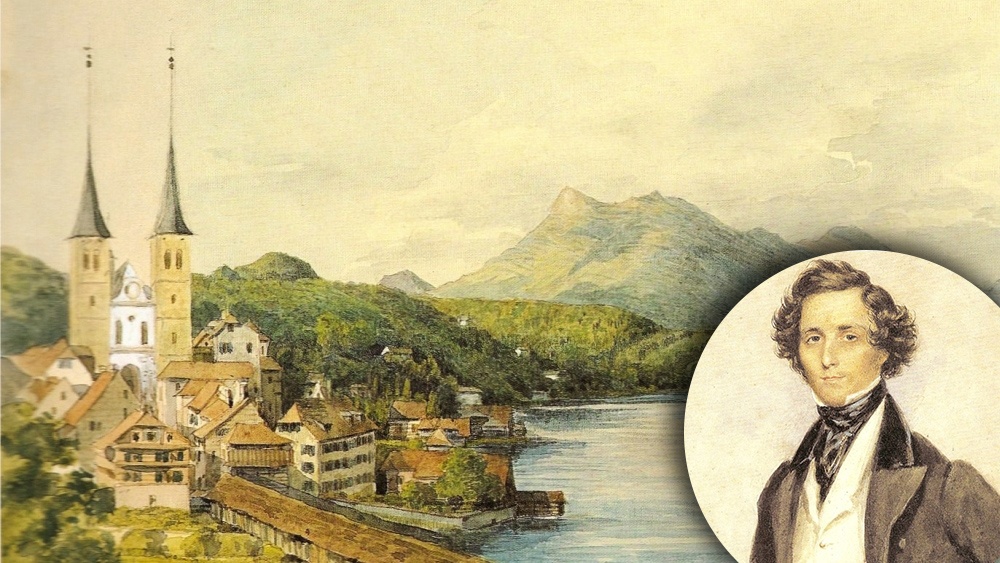

Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847)

Artist

Those who met Mendelssohn were awed by his many talents, chiefly in music. In a meeting later retold and passed down by Mendelssohn’s son Karl, a historian, Goethe declared that Mendelssohn was an even more sensational prodigy than Mozart after hearing the 12-year-old play and improvise at the keyboard. (Goethe would know: he met Mozart in 1765.) A skilled poet, Mendelssohn also spoke three languages (French, German, and English) and read two more (Latin and Greek). However, Mendelssohn was, most surprisingly, a talented artist, with a special fondness for landscape paintings. His work often documented his travels around Europe. For example, Mendelssohn produced the above sketch while in Scotland—a trip which later inspired his Hebrides Overture and Symphony No. 3, Scottish. Some of his paintings can be admired here.

Those who met Mendelssohn were awed by his many talents, chiefly in music. In a meeting later retold and passed down by Mendelssohn’s son Karl, a historian, Goethe declared that Mendelssohn was an even more sensational prodigy than Mozart after hearing the 12-year-old play and improvise at the keyboard. (Goethe would know: he met Mozart in 1765.) A skilled poet, Mendelssohn also spoke three languages (French, German, and English) and read two more (Latin and Greek). However, Mendelssohn was, most surprisingly, a talented artist, with a special fondness for landscape paintings. His work often documented his travels around Europe. For example, Mendelssohn produced the above sketch while in Scotland—a trip which later inspired his Hebrides Overture and Symphony No. 3, Scottish. Some of his paintings can be admired here.

Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860–1941)

Politician

Paderewski might be remembered by many as an accomplished Polish pianist and composer who advocated for the music of his home country. But Poles will no doubt remember his double life as a politician. He even briefly served as prime minister of Poland, albeit for less than a year. However, he governed at a critical period: on behalf of Poland, he signed the Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I, and oversaw important developments like the establishment of democratic parliamentary elections and a public education system. He also signed a treaty on the protection of ethnic minorities. Before retiring from politics for good in 1922, Paderewski continued to represent Poland abroad, for he was fluent in seven languages and was the only League of Nations delegate who didn’t need a translator.

Paderewski might be remembered by many as an accomplished Polish pianist and composer who advocated for the music of his home country. But Poles will no doubt remember his double life as a politician. He even briefly served as prime minister of Poland, albeit for less than a year. However, he governed at a critical period: on behalf of Poland, he signed the Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I, and oversaw important developments like the establishment of democratic parliamentary elections and a public education system. He also signed a treaty on the protection of ethnic minorities. Before retiring from politics for good in 1922, Paderewski continued to represent Poland abroad, for he was fluent in seven languages and was the only League of Nations delegate who didn’t need a translator.

READ MORE: Meet the pianist and statesman who helped secure Poland’s independence

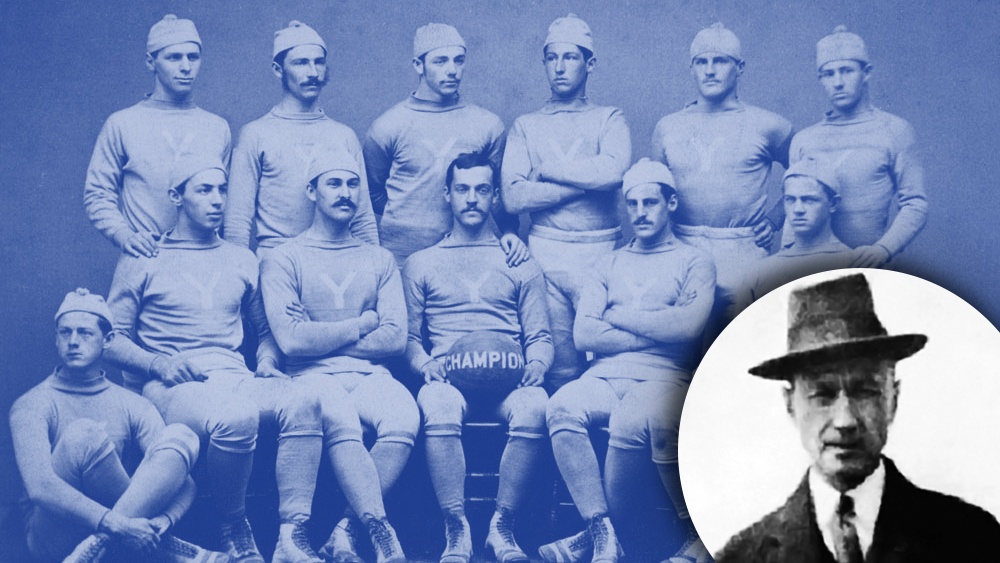

Charles Ives (1874–1954)

Athlete

Growing up, Ives seemed to be the epitome of a well-rounded kid: he was an accomplished keyboardist, becoming a church organist at just 14, but still carved out time to play sports. While attending the elite Hopkins School in New Haven, Ives was captain of the baseball team, which might explain why he once wrote in a letter to organist E. Power Biggs that playing his fiendishly difficult Variations on “America” was “as much fun as playing baseball.” He went on to become a valued player on the Yale football team. Even then, however, Ives knew his heart was with music. Mike Murphy, a famous track coach at Yale, lamented that it was a “crying shame” that Ives devoted so much time to music since he could have been a professional sprinter.

Growing up, Ives seemed to be the epitome of a well-rounded kid: he was an accomplished keyboardist, becoming a church organist at just 14, but still carved out time to play sports. While attending the elite Hopkins School in New Haven, Ives was captain of the baseball team, which might explain why he once wrote in a letter to organist E. Power Biggs that playing his fiendishly difficult Variations on “America” was “as much fun as playing baseball.” He went on to become a valued player on the Yale football team. Even then, however, Ives knew his heart was with music. Mike Murphy, a famous track coach at Yale, lamented that it was a “crying shame” that Ives devoted so much time to music since he could have been a professional sprinter.

Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951)

Painter

When he wasn’t emancipating the dissonance with twelve-tone works like Moses und Aron, Schoenberg liked to paint. In fact, his paintings were widely respected in Viennese artistic circles: the likes of Oskar Kokoschka, Carl Moll, and Wassily Kandinsky spoke highly of his work. (Schoenberg even briefly joined Kandinsky’s Blue Rider [Der blaue Reiter], an avant-garde group central to the burgeoning Expressionist movement.) Schoenberg’s paintings encompass a rather broad aesthetic range, sometimes in a short space of time. It’s still not uncommon to find his work displayed alongside those of other Viennese fin-de-siècle greats like Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele.

When he wasn’t emancipating the dissonance with twelve-tone works like Moses und Aron, Schoenberg liked to paint. In fact, his paintings were widely respected in Viennese artistic circles: the likes of Oskar Kokoschka, Carl Moll, and Wassily Kandinsky spoke highly of his work. (Schoenberg even briefly joined Kandinsky’s Blue Rider [Der blaue Reiter], an avant-garde group central to the burgeoning Expressionist movement.) Schoenberg’s paintings encompass a rather broad aesthetic range, sometimes in a short space of time. It’s still not uncommon to find his work displayed alongside those of other Viennese fin-de-siècle greats like Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele.

Sergei Prokofiev (1891–1953)

Chess player

When Prokofiev was five, he wrote his first composition, introducing him to a lifelong passion. Two years later, when he was seven, he found another: chess. Prokofiev was an avid chess player who befriended professionals like José Raúl Capablanca and Mikhail Botvinnik. In a major upset, he once beat the former in a simultaneous exhibition match in 1914. (The full story can be found on the Sergei Prokofiev Foundation’s website, which also details his love of card games.) Prokofiev also squared off against fellow musicians Maurice Ravel and David Oistrakh, in games that are still documented move-by-move. Oistrakh remembers how seriously Prokofiev took chess: “I wish you could see how excited he was drawing all kinds of colorful diagrams of his wins and losses, and how happy he was with each victory, as well as how devastated each time he lost.”

When Prokofiev was five, he wrote his first composition, introducing him to a lifelong passion. Two years later, when he was seven, he found another: chess. Prokofiev was an avid chess player who befriended professionals like José Raúl Capablanca and Mikhail Botvinnik. In a major upset, he once beat the former in a simultaneous exhibition match in 1914. (The full story can be found on the Sergei Prokofiev Foundation’s website, which also details his love of card games.) Prokofiev also squared off against fellow musicians Maurice Ravel and David Oistrakh, in games that are still documented move-by-move. Oistrakh remembers how seriously Prokofiev took chess: “I wish you could see how excited he was drawing all kinds of colorful diagrams of his wins and losses, and how happy he was with each victory, as well as how devastated each time he lost.”

John Cage (1912-1992)

Mycologist

Schubert may have been nicknamed “The Little Mushroom,” but it was Cage who really knew his Basidiomycota from his Ascomycota. By the time he founded the New York Mycological Society in 1962, the avant-garde composer already had a reputation for being sort of a fun guy in music, baffling listeners with works both irreverent and perspective-expanding. According to a recent article in Artsy, Cage’s interest in mycology was piqued while living in Carmel, CA during the Great Depression. For a while, the young artist could hardly afford food and wondered if the mushrooms around his house might be edible. He went to the local library to investigate, and never turned back. His fungi collection is currently housed at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Schubert may have been nicknamed “The Little Mushroom,” but it was Cage who really knew his Basidiomycota from his Ascomycota. By the time he founded the New York Mycological Society in 1962, the avant-garde composer already had a reputation for being sort of a fun guy in music, baffling listeners with works both irreverent and perspective-expanding. According to a recent article in Artsy, Cage’s interest in mycology was piqued while living in Carmel, CA during the Great Depression. For a while, the young artist could hardly afford food and wondered if the mushrooms around his house might be edible. He went to the local library to investigate, and never turned back. His fungi collection is currently housed at the University of California, Santa Cruz.