Pandit Satish Vyas visited the WFMT studios to perform on what he considers to be one of the most meditative and romantic instruments in the world: the santoor. It’s also one of the most ancient. The santoor was first mentioned in ancient Sanskrit texts, but has been incorporated into classical traditions only in recent decades.

The santoor is a kind of hammered dulcimer, a stringed percussion instrument played with mallets. “When we hit the string,” Vyas said, “it produces sound. It’s comparable to pianos; on the piano, when you press keys, hammers inside hit the strings, and that’s how sound is created. It’s interesting that there are instruments of this type all over the world,” Vyas said. “In Hungary and Romania there is an instrument called cimbalom. In Iran it is known as santur. In Greece it is santouri. There is yangqin in China.”

Vyas explained, “The santoor belongs to one of the most beautiful parts of India, the Kashmir Valley. In the olden days, many stringed instruments that came into existence were called some kind of ‘veena.’ One of them was shatatantri vina, and shatatantri means ‘100 strings.’ Later on, due to the influence of the Persians, the name was changed to santoor. Now it is used in Sufiana Mausiqi, local folk music in the Kashmir Valley, as an accompanying instrument.” Sufiana Mausiqi, as the name implies, is connected to Sufi philosophy.

A santoor and mallets (Photo: gurmatsangeetorg, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

“Today I am very proud that the instrument is recognized as a solo classical instrument. The entire credit goes to my guru, Pandit Shivkumar Sharma, who brought this instrument, singlehandedly, to the classical platform so that we can enjoy the popularity of this instrument around the globe now,” he said.

Sharma is also responsible for significant changes to the santoor’s construction in order to make it suitable for diverse kinds of repertoire. “The original structure of the instrument was with 25 bridges, each with four strings: that’s how we got 100 strings. My guru increased the number of bridges and strings. Finally, he settled on 29 bridges, each with only 3 strings, and for the bass notes, he used guitar strings. So in a nutshell, the number of strings got reduced to 84.”

“Of course, today, there is still some room for change,” Vyas said. “There are some santoors with 31 bridges, which helps widen the scope of notes available. You need a full octave to have a melody, which is what we call raag. My instrument gets about two-and-a-half octaves because there are 29 bridges. But with 31 bridges you get a full three octaves.”

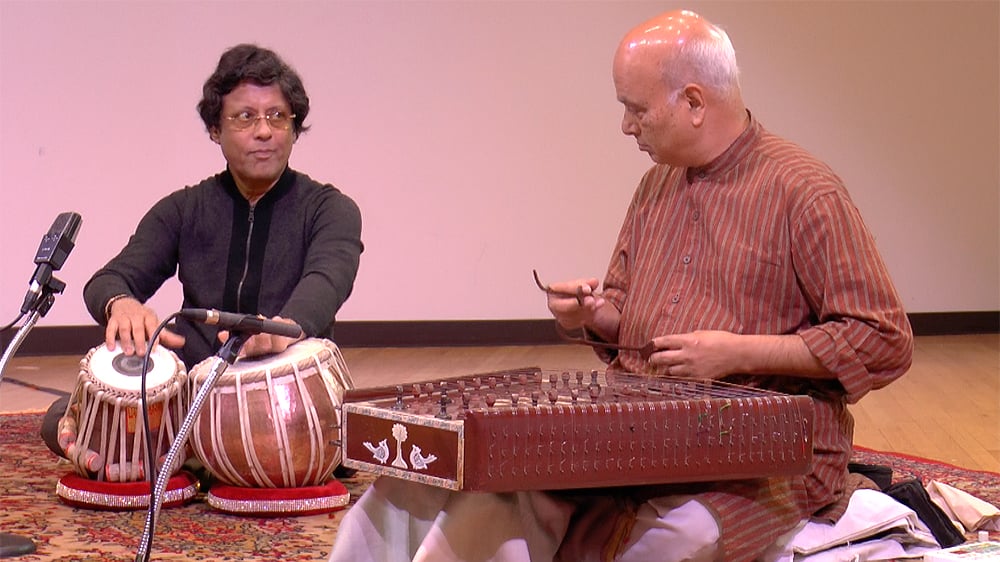

Vyas performed two works in the WFMT studios with his long-time collaborator, Pandit Anindo Chatterjee, who he described as “one of the topmost table masters of our country, contemporary with Zakir Hussain and Pandit Kumar Bose. We have played quite a few concerts together in India. We can go onstage without even practicing because we know each other so well.”

First, they played an improvisation on a raag called bihag. “In Indian music, raags are not just a collection of notes like a scale. They are melodies with a definite order of ascending and descending notes,” he clarified. In raag bihag, the sequence of notes that forms the ascent of the mleody is B C E F G B C, while the descending sequence is C B A G F E D C. The musical meter is teental, the most common tala, or musical meter, in Hindustani music: 16 beats divided into 4 groups of 4.

Vyas also played a dhun – a light classical instrumental work. In some music traditions, the designation “light” may be seen as pejorative, implying that something has been made “lighter” so that it’s easier to consume.

But “playing light classical music is more difficult than classical music,” Vyas said. “In classical music, there is no set thing you must play, it’s all improvised. You could write something down that has been played. You improvise within the parameters of the melody that you’re given. That’s how the music is extemporized.”

“Light classical music appeals to people because of the melodies and the rhythms, but when we say ‘light,’ it is not light in that sense. Again, it’s more challenging to play, but that’s my personal opinion.”

In the video below, the dhun is based on a light classical vocal work in which a person asks the listener take a message to their beloved. The original piece is called a dadra, named after its rhythm, since dadra is also a six beat meter divided into 2 groups of 3.