Pinchas Zukerman around the time Isaac Stern brought him to New York to study at Juilliard, c. 1962 (Photo courtesy of the artist)

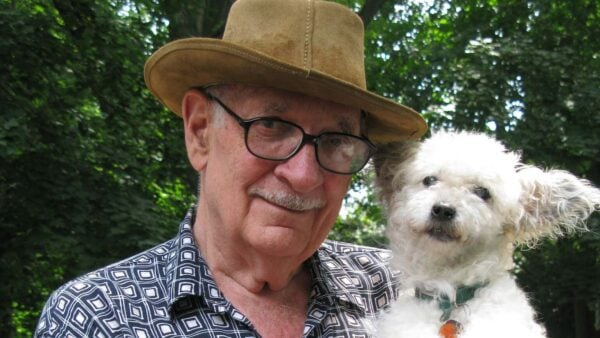

Violinist, violist, conductor, music director, and educator Pinchas Zukerman celebrated his 70th birthday on July 16, 2018. Backstage at Ravinia, he spoke about his life in music and unwavering dedication to his craft with WFMT’s Louise Frank.

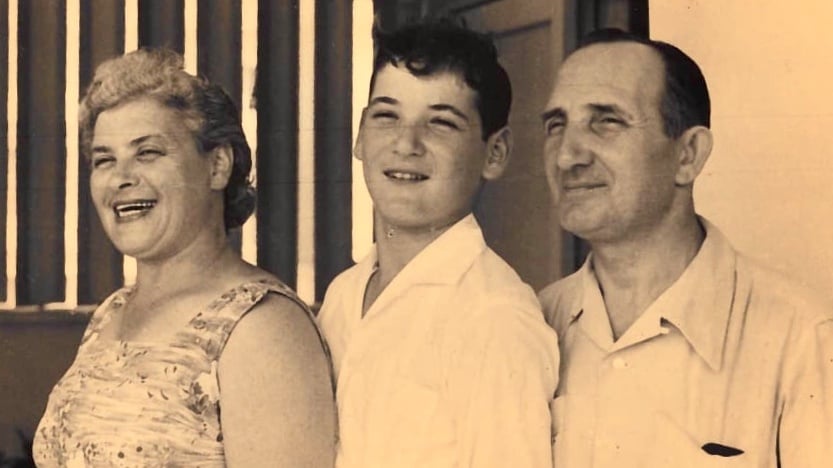

The story begins in 1948, along with the earliest days of the state of Israel. His parents, Miriam and Yehuda, met as Europe was recovering from the devastation of World War II, and they joined the survivors who emigrated to Palestine in search of a new life.

Pinchas explained that “at the end of 1945, the pogroms were horrible in Poland and my dad said to my mother, ‘We're going to Palestine.’ She said to him, ‘Yehuda, let’s go to Canada,’ – we had family there – ‘or to America.’ And he said, ‘No, our domicile is in Palestine.’ When I heard that I thought, wow, that's pretty good! He had a vision. It took over a year to get there.”

“A train to Berlin, he played the fiddle in the middle of the night to escape a dangerous encounter with Russians soldiers. From Italy they took that Exodus boat and almost didn't make it. A little over 4,000 people were on this little bathtub and it took about seven months from Italy to Tel Aviv. Imagine! And when they got there, of course, the Brits put them in Cyprus, but Cyprus was a camp. That’s when everybody met. Before that people went back to their home address in Vilnius or Latvia. They went back to Warsaw. They went back to Łódź. There was nothing. I don’t think people now realize that the whole place was demolished. It's not a question of one building standing. Nothing! So that surprised everyone. My dad did meet two brothers of his. One was in the Russian army, and one was in the Polish Army. And there was a sister in Tel Aviv who went in the 1930s.”

Pinchas Zukerman and his parents, Miriam and Yehuda (Photo courtesy of the artist)

Just because a father plays the violin doesn’t guarantee the son will inherit that same spark. But, music always felt vital to Zukerman. He reflected, “Can I say today that when I was 8 I knew I was going to be talking 55 years later about my journey as a fiddle player? There's no way! However, there was an attachment. There was a kind of inner energy and I knew I had to play music because I heard music and music was like drinking water, like needing the sun. For me, it's never been a vocation. Never! A lot of people think of it as a tool. I don't. “

He lived a love story with music from the earliest times. And that helped him through the changes that came when Isaac Stern found out about him and brought him to New York to study at Juilliard. One day he was a talented kid growing up in Israel; and then in 1962 he found himself as a teenager far away from home.

“When I was 13-and-a-half I was plucked away. My father thought it was a very good idea. My mother, of course, said, ‘No.’ And then he said, ‘Look, we have no choice. We have no money. He has to have an education. He has an opportunity here to have the best there is.’ Not that I had bad education. From day one, I started to play little duets with my father, and then chamber music with Ilona Feher at the conservatory. All these extraordinary people – after the war they came. Oedoen Partos and Ben-Haim and all these people were there. There was a community that was rebuilding a whole resource of emotion, and beautiful stuff that was being written. Isaac and Vera Stern created the America-Israel Cultural Foundation. We played for all the dignitaries, Casals and the Budapest Quartet and Maureen Forrester and a whole bunch of people that always came to Israel, usually during the summer. We had a wonderful festival. And so I played.”

In many ways, those early experiences helped inspire his own style of mentorship. For 25 years, he and Patinka Kopec have taught exceptional young musicians through the innovative Zukerman Performance Program at the Manhattan School of Music.

As an educator himself, Zukerman hopes to convey what he learned from his own mentors such as violinists Ivan Galamian and Stern. He encourages his students to explore a wide range of interests and experiences beyond honing their technical proficiency. He still practices his scales every day, remains insatiably curious, and that's just the beginning.

“I make them listen a lot. Isaac said to me, ‘Pinky, be a sponge.’ I said, ‘A what?’ He said, ‘A sponge!’ I said, ‘OK, I get it. I get it!’ So I was a sponge! I went to many rehearsals. I went to Carnegie Hall to see Fischer-Dieskau. I went to Janet Baker at Hunter College, and I heard the Guarneri Quartet play. Then I started playing with these people! The first time playing with someone like Fischer-Dieskau I learned from the way he projected. He stood on his toes when he went to sing pianissimo. Oh man…that was a lesson and a half! So I teach that a little bit, in different ways of course, we’re not using the voice, but there are tremendous similarities.”

Of all of the collaborators that Zukerman has known over his long career, his violin and viola are two of the most important and personal. His violin is the 1742 Guarneri del Gesu that previously belonged to the great violinist, composer, and teacher Samuel Dushkin. The viola is a Guarneri composite with a back and ribs by Andrea, the grandfather of Joseph ‘del Gesù,’ and a top by Giuseppe Guarneri I, or 'filius Andreae,' who was Joseph's father. Zukerman said that he knew that those instruments were right for him the first time he played them.

“So I have 102 years of the same Guarneri DNA! And I don't ‘play,’ I travel with these guys. The viola I met in London about 30 years ago. It’s one of the great, great instruments. There was a lady who owned it for 45 years and had to give it up because she retired from the orchestra. The Dushkin I met in 1964 in New York. We were at the Wurlitzer shop and there was Fritz Kroll and Milstein, Ruggiero Ricci, and a whole bunch. I was just standing there and they’re all playing the fiddle. Sam Dushkin played a little bit, and then said, ‘Come on, play a little bit!’ I picked it up and I put my bow on the strings and it's like somebody turned on a microphone. They all turned and said, ‘What did you do!’ I started to play and I couldn’t stop! It was one of those amazing moments. So I said to Sam, ‘You think I could? Maybe one day? Somehow?’”

“Well, he passed away. His wife decided to sell it in 1980 and Howard Gottlieb here in Chicago, he was so nice to me. He was the bank, really, to help me out and buy the fiddle. And I will play on it, probably over 50 years, which is what Jascha Heifetz did! Jascha played on his for 50. Dushkin also for 50. I’m the fifth owner of this fiddle which is, in itself, a miracle. So, I'm lucky, that’s all. And I love playing it, today probably more than ever before. You just learn to create more colors from an instrument like that. Ach! It’s amazing.”

Pinchas Zukerman performing the Elgar Violin Concerto with Zubin Mehta and the Berlin Philharmonic (Photo courtesy of the artist)

Over the long arc of Pinchas Zukerman’s prolific career, he feels he has gotten back more than he has given.

“Oh, yeah! But when you say that, I get a little bit, I don't know. The brain goes a little funny because I don't know what I'm doing out there to those people. They come and tell me that. They'll give me a hug, you know, and say, “Wow, that’s so beautiful.” The most important thing I teach my students, I say, ‘Tomorrow morning, you better get up and play those scales. Don't ever think that you're good. You could always be a little bit better.’”

“And that's something that was taught to me as a value system maybe primarily because I was growing up at a time when things were so new again, with an old, established value system, of home, of culture, family, the shtetl. The curiosity of it all. Luckily I was able to do that in my lifetime. So these are all interconnected. Some of it understood, some of it not understood. I just keep doing what I have to do and that's all.”