A small sample of WFMT's collection of classical LPs

Tonight’s selection is determined as much by the caress of the finger across the spines as the music itself. The choice is slid from the collection into the waiting hand of the enthusiast. It is cradled gingerly in the arm as the other hand slides off the glossy jacket and then the sleeve to reveal multiple glistening shades of black reflecting off the vinyl. The disc is reverently placed on the turntable, and the tone arm is raised in anticipation of the full-frequency stereophonic sound immersion. The multi-sensory, ritualistic experience of listening to a vinyl record transcends any digital playlist. Whether new or vintage, you’ll want to make sure that your prized classical albums are well cared for.

This is increasingly important, because vinyl has seen a resurgence in recent years with experience seeking millennials driving the sales of these treasures. The statistics predict that vinyl sales will overtake CDs, which is looking evident given that 827,000 vinyl records were sold on Record Store Day in the US this past year alone.

Vinyl is also a very re-sellable commodity. Mobile Fidelity’s Rob “Rob the Record Guy” Gillis notices yet another trend among customers purchasing multiple copies of a pressing to make a profit. “A record that we put out last year in a limited pressing for $100 is now selling for $500 or $600. Some people bought two copies, one to listen to and one to resell.”

Whether you’re an audiophile aficionado, a collector, a dealer, or a tactile-seeking millennial, you will need to care for your prized vinyl so that it will yield decades of listening enjoyment. That means cleaning, storing, and handling them properly. I spoke with several experts in the field who were happy to share their knowledge of the subject.

How a record is made

To begin, let’s learn a bit about how a vinyl record is made. I first spoke with Chicago/Nashville based mastering and cutting engineer Margaret Luthar whose career has taken her to Alberta, Belgium, Norway, Chicago, and now Nashville. She describes her work as being the end of the creative process and the beginning of the manufacturing process. If the recorded album is destined to be a vinyl record, it is her job to optimize the audio for the medium. She then literally cuts the music into an acetate-coated aluminum disc called a lacquer disk with the aid of a lathe. A lathe is a machine used to cut the audio waveform into a lacquer. The material is very fragile and highly flammable, so great care is taken to collect and dispose of the residual filings, referred to as chips.

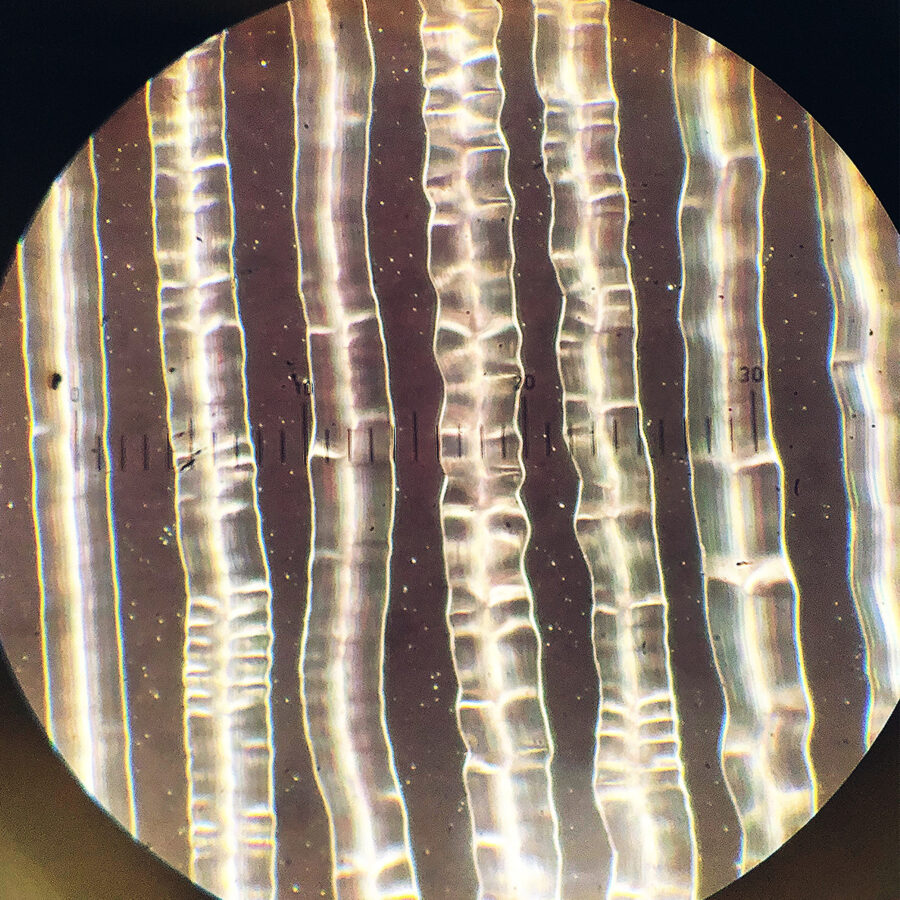

Record grooves under a microscope (Photo courtesy Margaret Luthar)

At this point, the master lacquer disc is playable, but Luthar doesn’t recommend this. “Temperature and humidity affect it. It is also a soft substance that could scratch easily, so you want to have it plated within 72 hours because the grooves will start to change.” Luthar’s lacquer would then be sent to a plant like Quality Record Pressing (QPR), one of the world’s premier pressing plants. For over 35 years, owner Chad Kassem has built QRP into a thriving business of over 100 employees. His roster of pressings includes the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, the 50th anniversary addition of the Beatles’ Abbey Road album, and Fritz Reiner conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, as well as 50 other RCA Living Stereo recordings.

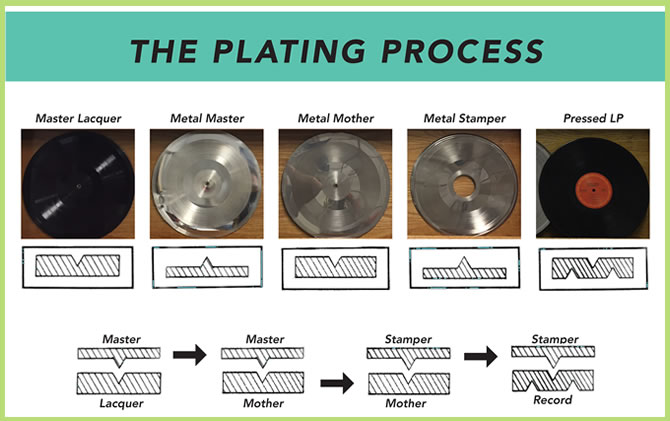

After QRP receives the lacquer from the mastering engineer, it progresses through a 3-step process before becoming an LP. First, it is plated, which Kassem describes as follows, “When you cut into a lacquer, you cut grooves. That you can play. Then you spray silver on it. You then pull that apart, now you have what is called the metal master or the father (the inverse of the lacquer). Then you make the mother (also referred to as the metal mother) from the father, and now you can play it again. Then you make the stamper from the mother, and now the grooves are sticking out again.”

Graphic illustrating the plating process (Image courtesy QRP)

The stamper is then aligned on a machine. Meanwhile, the PVC is melted and mixed with other components to form a “biscuit,” which will eventually be pressed into an LP. The labels are fixed above and below, and the biscuit is then subjected to extreme pressure between the plates. When the process is finished, the record falls out and the flashing (excess vinyl material) is trimmed for a smooth edge. Some plants, like QRP, also use a manual press. With this machine records are pressed by hand, one at a time. This is a very slow and labor-intensive process, but the reduced vibration produces a superior sonic result.

It should also be noted that a stamper, whether used on a manual or an automated press, can only produce about 1000 records. This is a reason why albums are reissued or might go out of print. Purchasing a reissue might be desirable because as Rob “The Record Guy” Gillis adds, “There’s a difference between various pressings and mastering. Let’s take Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. You may own six copies of the same performance because they’re all different. They have different textures and feels as well as different sonic signatures.”

Caring for your collection

So now that you have amassed a record collection, what is the best way to care for and clean your precious possessions? One classic approach to cleaning is wood glue. The thought is, that when it is spread across a record, allowed to dry, and then peeled off the surface, it removes dust and debris from the grooves. Along with putting your records in the dishwasher, this is a classic approach, but it makes Perfect Vinyl Forever owner Steve Evans cringe.

Evans became an avid record collector in the 80s, but discarded his collection at the advent of the CD. He grew to miss the audio quality that the analog medium provided, so he resumed his passion for vinyl. He refers to himself as a DIY guy at heart, which caused him he set out to build his own record-cleaning machine. He not only did this but perfected, it allowing him to clean over 30 records an hour in an ultrasonic bath. He now offers this as a service, where customers can send their collections to him to be cleaned. According Evans, this process needs to be done only once, provided these three guidelines are followed:

- Use a dry carbon fiber brush to remove any surface lint or dust before playing.

- Never get your record wet again.

- Never blow dust off of your records.

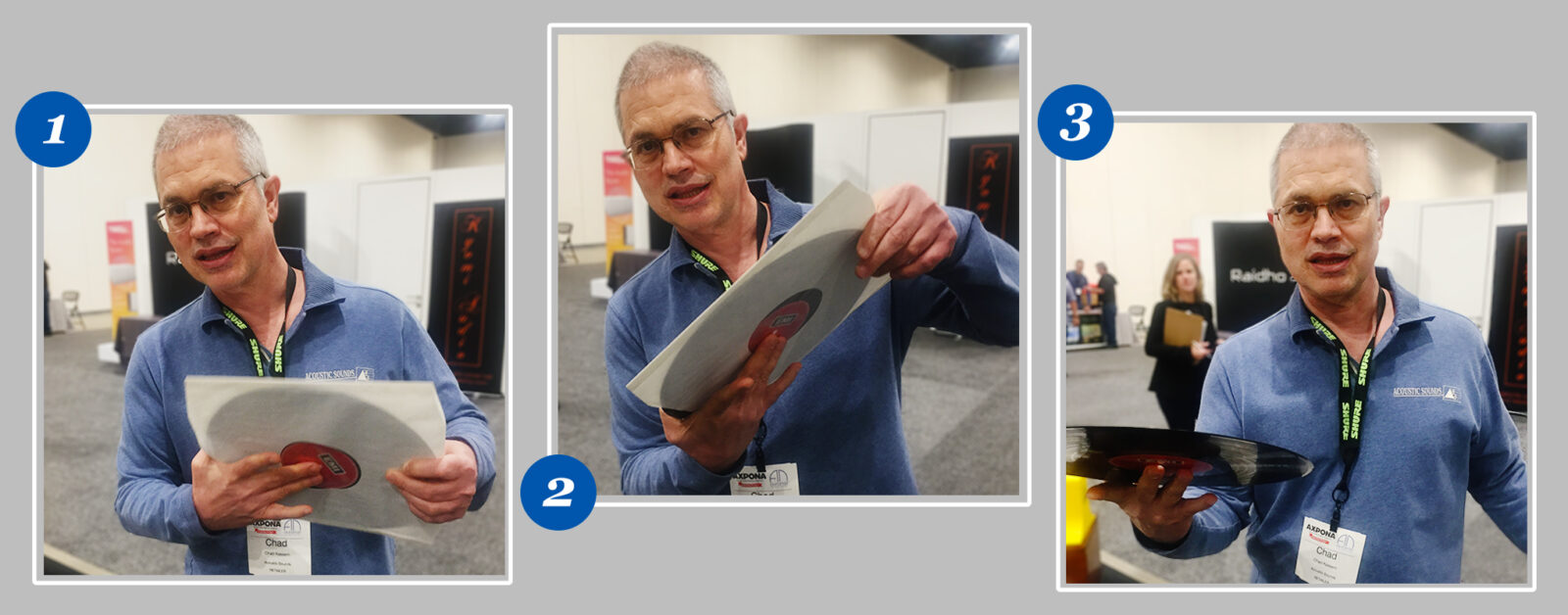

However, if sending out your collection is not an option, or you feel that cleaning is part of the ritual and want to do it yourself, there are some other options. Kassem puts it simply, “Don’t get it dirty! Keep your fingerprints off. You wouldn’t believe how much oil you have on your hands. Treat it with respect, and put it away after listening.”

Deceptively simple: Chad Kassem demonstrates how to handle a record (Photo: Mary Mazurek)

The fact is that we live in the real world and try as we might, fingerprints and dust are going to get on our albums. Then what? You might invest in a home ultrasonic record cleaner, which not only takes care of the debris, but also removes an only recently-discovered coating on the album, which results from the manufacturing process known as the release agent. Dr. Charles Kirmuss of Kirmuss Audio describes that “…when you heat a plastic, a lubricant bubbles to the surface of the plastic, which facilitates the record to pop out of the press. It thus coats the record.” What’s worse is that it attracts dust, and when the heat of the stylus hits the groove, it micro-welds the dust particles into the release agent, resulting in audible clicks and pops. According to Kirmuss, removing this release agent with the ultrasonic process reduces clicks and pops and results in increased signal (approximately 1.5dB).

Kirmuss’ passion for music and broadcasting, which brought him to love vinyl also inspired him to create an at-home ultrasonic cleaning system. He explains, “With ultrasonic cavitation, bubbles are generated and explode, and then they create upon that explosion a plasma wave that moves the water in the tank between 300 and 1500 mph.” However, he warns that vinyl repels water because of its positive charge. Therefore, he designed surfactant solution to attract water to the vinyl, thus allowing for exceptional cleaning and restoration.

He recommends repeating this process about every three years to remove any accumulated debris like dust, skin oils, cigarette smoke, and fungal colonies. You might not think that fungus would be a problem on plastic, but Kirmuss explains that soy is often incorporated into the PVC mixture, not to mention that the paper sleeve the record is stored in has a sugar content, which can contaminate the record. Repeating the process every three years should ensure a clean record and superior sound. Between cleanings, he recommends proper handling and storage, as well as using a carbon fiber brush to remove static and dust.

But what is proper handling and storage? For this, Evans recommends handling the record only by the edges and storing them vertically in a temperature stable environment. Stacking them horizontally, he adds, subjects the vinyl to uneven pressure, which can cause warping. If your record does warp, there are flatteners, which apply both pressure and heat over time to straighten the album. Kassem says that this process is pretty good but is expensive and doesn’t always work, so it is best not to let it happen in the first place.

Instead of cardboard sleeves, which can scratch the record, Kassem recommends using rice paper sleeves, which are gentler and reduce static. These precautions are worth taking because as Kirmuss emphasizes, “With records, we can listen to artists who are no longer here, and some vinyl is so precious that in part, we are all responsible as custodians. It’s not about the business, it’s about keeping them for the next generation to enjoy.”

The vinyl trend remains in full swing for both old and new records, which is something Luthar hopes will continue. Kassem is certain that it will, because “the record is more like a religious experience. It’s like a ritual. [When you play a record,] you’re going to sit down and give yourself to the music and let it envelop you and pull you in.” In a fast-paced world, this experience is something that we could all benefit from.

Follow this checklist to care for your vinyl collection!

Then, enjoy decades of listening to your favorite records

Mary Mazurek began her career at WFMT 1993 as an overnight board operator. One of her duties was to pull and clean records with a Keith Monks record-cleaning machine for the next day’s programming.