As our sister station, WTTW launches 10 Buildings that Changed America, we at WFMT thought perhaps it was time for some reflection on the art of music composition.

As our sister station, WTTW launches 10 Buildings that Changed America, we at WFMT thought perhaps it was time for some reflection on the art of music composition.

WFMT’s 10 Pieces That Changed the World offers a full day of musical giants, pieces of music that turned the art form into something it hadn’t seen. It is important to say that WFMT is not suggesting these 10 pieces are necessarily the 10 greatest works, but that they revolutionized music. Nothing written after them was quite the same as the music that came before.

Monteverdi: L’Orfeo (1607)

Claudio Monteverdi

“Monteverdi turned the aristocratic spectacle of Florence into modern musical drama…”

—Henri Prunières

It was not by design, but by happy coincidence that the first two pieces on the list pertain to Greek mythology’s most famous musician, Orpheus. Although Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo came early in the history of opera (within ten years of the very first), it was opera’s first masterpiece, and set the formula for opera: the use of recitatives, arias, and choruses; it even has an overture of sorts (called Toccata).

Monteverdi was the first to realize the full potential of the genre. Henri Prunières has written: “Monteverdi turned the aristocratic spectacle of Florence (where the first operas were performed and composed) into modern musical drama overflowing with life and bearing, in its mighty waves of sounds, the passions which make up the human soul.”

Gluck: Orfeo ed Euridice (1762)

Christoph Willibald Gluck

By the time Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice came along, opera seria had become stultifyingly predictable and formulaic, using and re-using the same embellishments from the great singers of the late baroque. In the year 1762, Gluck and his librettist, Calzabigi, sought to completely reform the genre of opera. They stripped away excess: only 3 characters in Orfeo. The spectacle, pageantry, and embellishments were eliminated. Ballet, which had been occasionally used, was made part of the story. In Gluck’s Orfeo, everything exists to further the story and add realism.

Beethoven: Symphony No. 3, Eroica (1804)

“That Beethoven was capable of producing the ultimate musical definition of heroism in this context is itself extraordinary, for he was able to evoke a dream of heroism that neither he nor his native Germany nor his adopted Vienna could express in reality. Perhaps we can only measure the heroism of the Eroica by the depth of fear and uncertainty from with it emerged.”

―Maynard Solomon

Beethoven’s Eroica has been called, “The greatest single step made by an individual composer in the history of the symphony and the history of music in general.” Prior to this work, which includes Beethoven’s first two in the genre, the symphony was a classical form in sound and structure. With Eroica, everything is new: the discords, the displaced accents, and unusual modulations; its scale (Eroica is twice as long as almost any symphony before it); its use of a funeral march for one of its movements; its drama-everything.

Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 (1823)

Beethoven is the only composer who is represented twice on our list. His 9th again breaks every mold. He chose, for the first time, to use soloists and chorus. He inverted the slow movement with the scherzo (placing the Adagio as the third movement), then proceeded directly into the finale without pause. And then, to further manipulate the traditional, he makes the entire, sprawling 4th movement a theme and variations!

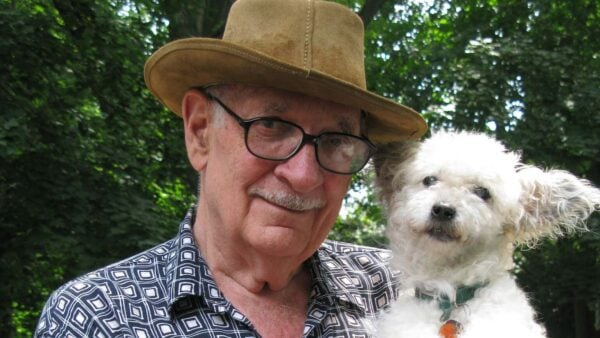

Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique (1830)

Hector Berlioz

Here is yet another symphony that shattered what went before. Berlioz was never to follow in anyone’s footsteps-he was a true romantic; he was only 27 when he wrote this piece. Never had a composer followed such a literal and detailed programme in a symphony: a young musician poisons himself with opium in a fit of amorous despair. He has strange visions which translate into musical thoughts and images. The beloved woman has become for him a melody, like a fixed idea, which he finds and hears everywhere.

This was a work more fantastic and macabre than any other. It demanded an enormous orchestra (Berlioz was famous for that). It was more emotionally turbulent than any work that had gone before. In place of the usual theme and development sections, Berlioz introduced the idée fixe: a recurrent theme that appears throughout the work.

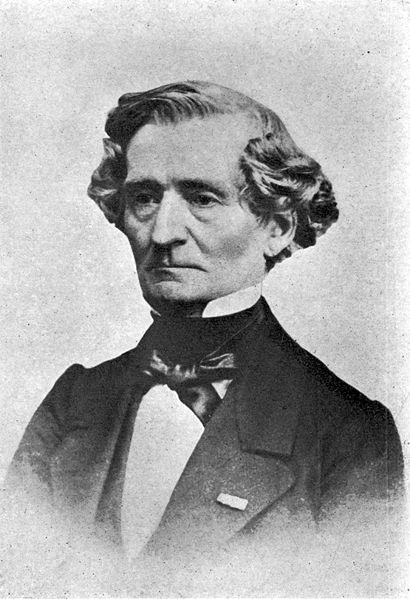

Liszt: Piano Sonata in B-minor (1853)

Franz Liszt

This is the only piano work on our list. Liszt called it a “sonata,” but it is anything but that, in the traditional sense of a highly structured, multi-movement work that works out thematic ideas in a prescribed way. All form is abandoned in this work-it is more like a fantasy or a rhapsody. Though the piece lasts some 30 minutes, it has only one movement. Liszt lets his imagination have free reign and lets the piece go wherever he pleases. The “sonata” was never to be the same.

Wagner: Tristan und Isolde (1859)

Richard Wagner

“With this one composition, Wagner revealed the scope of his vision and guaranteed that music would never be the same. Reaching back to the Middle Ages for its subject, Tristan cast its long shadow far into the future—stretching across the twentieth century’s first modernist masters, from Debussy to Berg, all the way to Radiohead…”

—Phillip Huscher

It has been said that modern music started with the opening chords of Tristan, offering complete harmonic ambiguity which reaches, and twists, and turns without resolution until 5 hours later!

One commentator wrote that “few works in the history of Western music have so potently affected succeeding generations of composers.” Extreme chromaticism reigns here-constantly changing harmonies and shifting keys, which pave the way for Mahler, Reger, Strauss, Schoenberg, Debussy, and many others back to Wagner.

See a video about Tristan.

Debussy: Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (1894)

Claude Debussy

What sets this apart for “changing the world” of music is partly tonal ambiguity (listen to the opening flute solo, which purposely sets up the absence of a key), but even more so, the exotic colors in the orchestration. We have here true musical “impressionism” with the vagueness of sound and wash of colors that many composers were to later take up as the 20th century progressed.

This piece changed the world because of its orchestration: a large orchestra, but quietly used; divided and muted strings, harp and woodwinds playing in a low register; horns and trumpets used rarely and often muted; there’s a large percussion section, but, again, used sparingly for color.

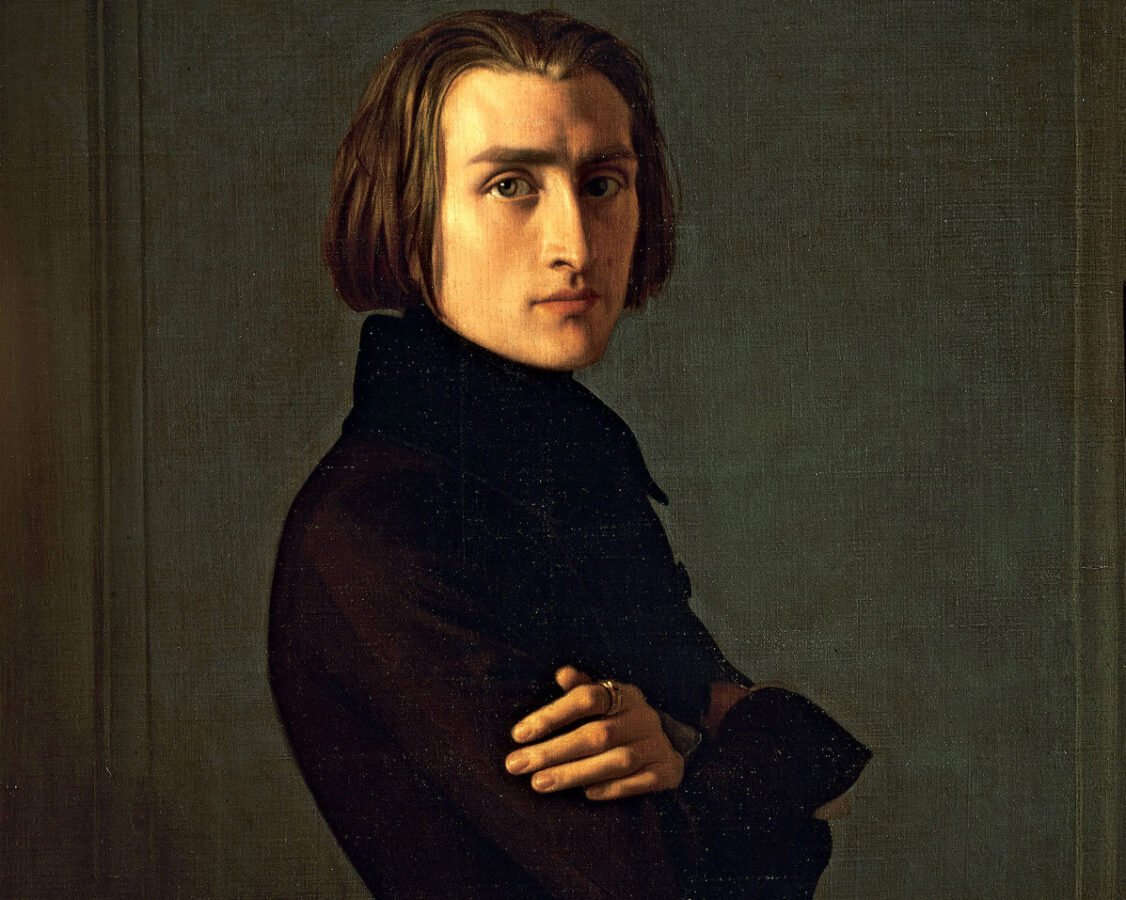

Schoenberg: Pierrot lunaire (1912)

Arnold Schoenberg (Photo: Florence Homolka / Attribution)

Although Schoenberg is known for his development of “twelve-tone” music, this piece pre-dates that. We have here not only the complete break down of tonality, but the composer’s pioneering use of a non-singing vocal technique; a “speaking voice” or Sprechstimme. The “singer” only approximates pitch. Often the text has nothing to do with what is going on in the accompaniment. This is now musical expressionism in all its abstraction; complex and unorthodox.

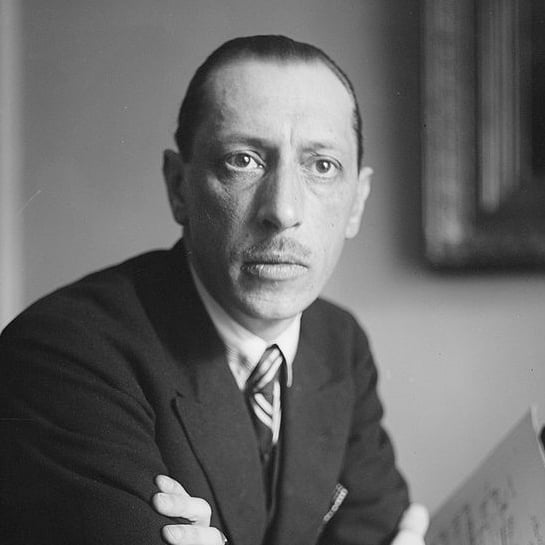

Stravinsky: Rite of Spring (May 29, 1913)

Igor Stravinsky

Although it has been pointed out that the famous riot that this piece incited came more from the choreography than from the music, this is still one of the most radical and influential pieces ever composed. We can point to the orchestral colors (when had a bassoon ever been used in this way?) and the “modern” harmonies, and orchestral outbursts, etc., but now we have rhythm as the catalyst of change; driving, harsh beats, often in unexpected places; the syncopation and the savagery. Percussion took center stage with this work.