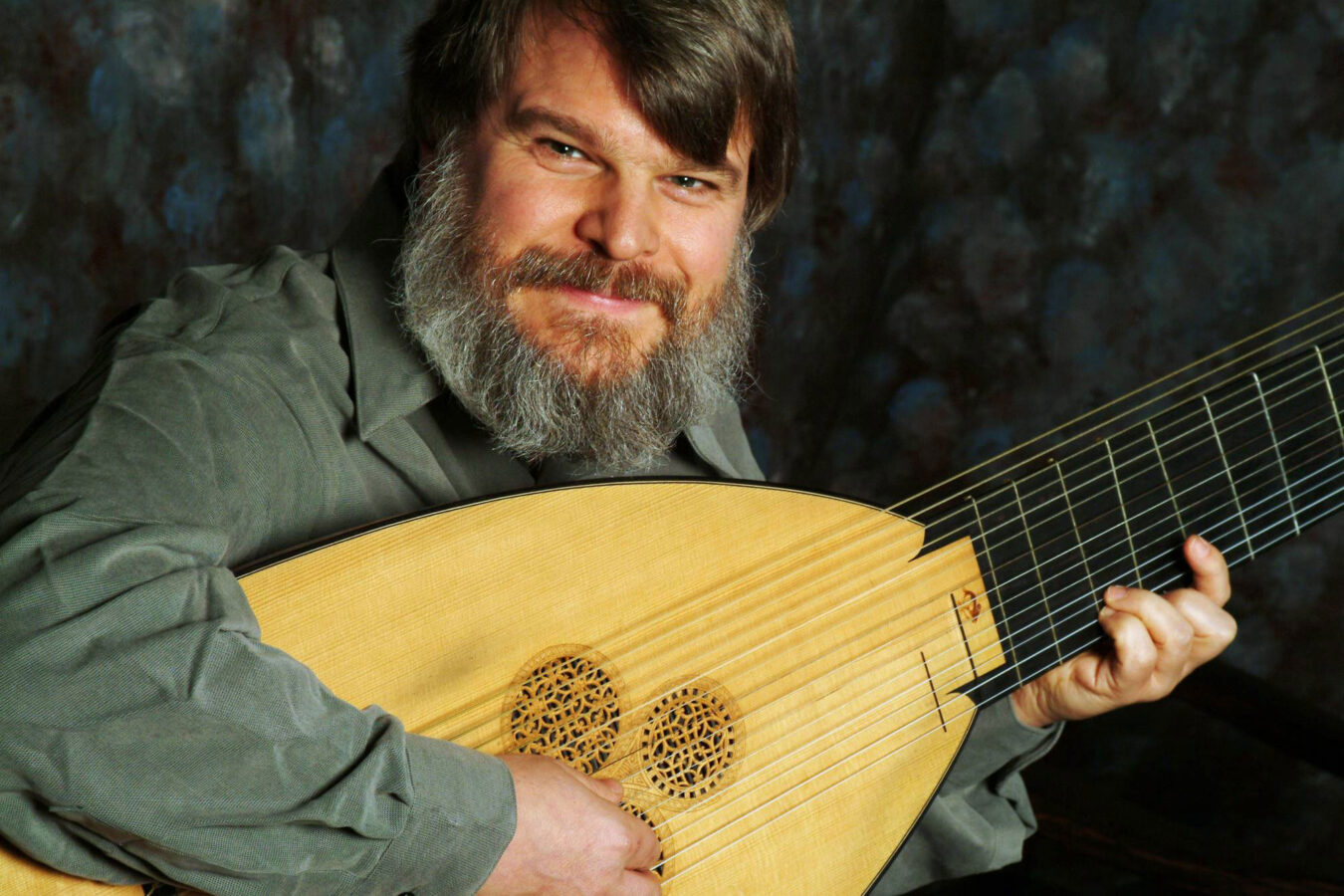

Lutenist Paul O’Dette (Photo: Jennifer Girard)

Paul O’Dette is one of the most sought-after lute players in the world. In addition to being an active soloist, O’Dette is the co-artistic director of the Boston Early Music Festival, teaches at the Eastman School of Music, and records extensively, with credits on over 120 albums. His recording of Charpentier’s La Descente d’Orphée aux Enfer won the 2015 Grammy for Best Opera Recording.

Before his upcoming solo recital presented by the Segovia Classical Guitar Series at Northwestern University on Saturday evening, O’Dette spoke about his Grammy-winning recording and his instrument.

“I have been a great fan of Charpentier for a long time,” O’Dette said. “To me, one of the great masterpieces is his little opera La Descente d’Orphée aux Enfer. It’s an incomplete work – it only survives with the first two acts. You get as far as Orpheus coming out of the Underworld with Eurydice, but you don’t get the moment when he turns back and everything goes wrong.”

But, having an incomplete score didn’t stop O’Dette and his colleagues from performing this piece. “We staged the piece in 2010 at the Boston Early Music Festival paired with a pastorale by Charpentier called La Couronne de Fleurs. The pastorale is a poetry contest, so in the staging, we included Orpheus as one of the singing contestants. So we started with La Couronne, then we performed La Descente d’Orphée. The moment when he comes out of the Underworld in Orphée, we skip to the end of La Couronne.”

The staged version is a bit different from the studio recording, however. “When we recorded it we decided to separate them on the album so it made a little more sense to listeners,” he explained. “So, we did them as two separate pieces. But we had a magnificent cast with the wonderful Aaron Sheehan in the title role.”

O’Dette and those who appeared on the recording were also a bit surprised by their Grammy success. “We were amazed when we were nominated for a Grammy, because it’s a chamber opera. We were nominated several times in the past for big operas of Lully, and we had another one in the can – the opera Niobe by Agostino Steffani – we thought that might attract the attention of the Grammy voters. But we ended up winning for the Charpentier!”

From his extensive experience performing diverse repertoire, O’Dette is undoubtedly one of the most knowledgeable musicians in the field of early music. Since he’s also one of the world’s leading authorities on the lute, he answered a few questions about his instrument.

What is the origin of the lute?

The oud, from which the lute descended (Tdrivas, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

“The question of the origins of plucked string instruments is a very complicated one. There are a lot of gaps in our knowledge of which instruments came from the Far East, which came from India, and which came from the Middle East. But, to pick up the story where it’s relevant for us: the oud, a plucked string instrument that was popular in Northern Africa and the Middle East during the Middle Ages, was the forerunner to the lute. It is still widely played throughout those areas today. It was introduced in Southern Europe, first in Sicily and then in Andalucía. There are a lot of pictures from the 12th and 13th centuries of people playing these instruments. These were unfretted because in Middle Eastern music there’s often a lot of sliding and bending of pitches which wasn’t the case in Western European Medieval music. Originally, they were played with a quill – usually an eagle quill – which was like a modern flat pick. Gradually, Europeans added other changes that made the instrument more suitable to their music. For example, Europeans added frets.”

What are some of the earliest pieces of music for solo lute?

A particularly lavish edition of lute tablature from Capirola’s Lute Manuscript of 1517

“In the second half of the 15th century, some German players realized it would be possible to play polyphonic music, that is music with more than one voice, if they started plucking instead of picking individual fingers of the right hand. That was really the start of the solo lute repertoire as we know it today. It developed in the end of the 15th century.”

How popular was the lute during its heyday?

Gerrit van Honthorst, The Concert, 1623

“The lute was the most popular instrument in its heyday. It was ubiquitous in the 16th century and held a position roughly equivalent to the piano in the 19th century, which was the instrument that every educated member of society learned how to play. The lute was the first instrument that people would keep in their household, and it was the instrument of the court virtuoso musicians. The most prestigious courts of Europe engaged in very heated bidding wars for the best players.”

How many kinds of lutes are there?

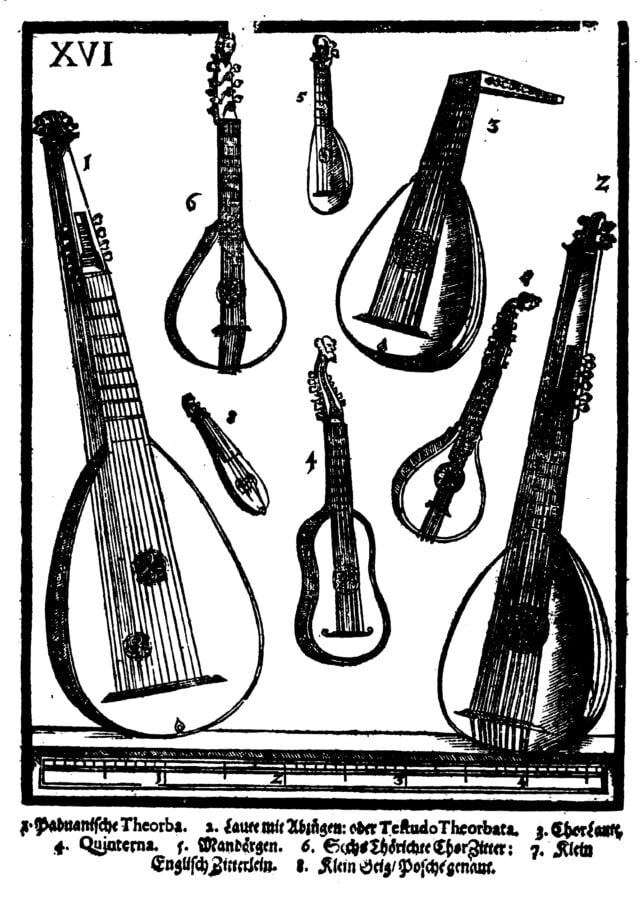

A page from the Syntagma Musicum by Michael Praetorius

“The lute is not a single instrument but a whole family of instruments. Lutes came in all different sizes: soprano, alto, tenor, bass, great bass, and even little sopranino instruments. They could be played together in groups called consorts and you would create a wider spectrum of sound and a wider range of pitches. There were instruments with gut strings and instruments with metal strings, like the bandura. There were some instruments played with a pick like the cittern, which is a wire strung relative to the lute. The guitar evolved from also a member of the family which had been altered in the 15th century for bowed string instruments – the viola da mano or vihuela da mano, which is a waisted instrument with a shape like a guitar, and a less rounded back than the lute. The vihuela in Spain is basically a guitar-shaped lute. All of these instruments evolved in the 16th and 17th centuries to suit the repertoire that was being composed at the time.”

How many strings do lutes typically have?

Lute Players (The Fool), Frans Hals, c. 1623-24

“Because the bass register became more and more important in all music throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, some changes to the instrument helped expand its range. All instruments were expanding the bass ranges. So the tendency was for the lute to acquire more and more strings. In the 16th century, the instrument started with 6 pairs of strings. By 1600, it had 8 or 9 pairs of strings. By the early 17th century, it had as many as 14 pairs of strings.”

How are lutes tuned?

“In order to make the string length long enough for the strings to resonate at the correct frequency, it was almost impossible for the left hang to conveniently grab the string to play big chords. So what they did was to add a second pegbox which allows you to have two ranks of strings: the short strings that you finger with the left hand, and the longer bass strings which would only be played as open strings like the harp. There were two versions of this instrument: one is the archlute – essentially a Renaissance lute with extra bass strings and which had the same time – the other is the theorbo (or chitarrone) which had a longer string length for the short strings. But in the theorbo, it was impossible to tune some of their strings in their correct octaves.”

The lute can be so soft, did anyone ever try to make it louder?

The Allegory of Music, Laurent de La Hyre, 1649

“There is one and only time in the history of the lute that people were trying to develop a louder instrument. In the 16th century, people felt loud music was vulgar, obscene, and unrefined. They felt that the most beautiful, the most refined, the most sophisticated music was performed at a conversational level. That’s one reason the lute was so beloved – it had a delicacy and intimacy that resulted in very expressive and meaningful music.

“When the lute was used an accompanying instrument for performances celebrating the wedding of Ferdinand de Medici, another fascinating change was made to the lute. This is the only time in the history of the instrument people wanted to make it louder. In order to hear the lute in a space big enough to hold 1,000 people,

“They took a bass lute and tuned it up as high as it would go. They knew the top string would break immediately, but they didn’t care – they wanted to see what would happen with the middle and low register. Those lower registers became much more brilliant and resonant. They kept tuning higher and higher, eventually breaking the second string. When they got to the breaking point of the third string, they found this was when the instrument sounded best.

“Because the instrument was used as an accompanying instrument to virtuoso vocal music, it didn’t matter what octave the notes were. So rather than invent a new tuning, they simply put thicker strings on in place of the first and second strings tuned an octave lower than the strings would normally sound. So the singers could play the same chords with the same fingers they learned for decades without having to learn. But, as a result, the third string is the highest sounding one on the instrument. This kind of tuning in which the sequence of the strings is “out of order,” without the highest string on top, that’s called a re-entrant tuning. Quite a few plucked instruments that use this kind of tuning, like the baroque guitar for instance. The lowest pitch is in the middle, rather than at the bottom.”

Is there a “standard” tuning for lutes?

A late Renaissance, early Baroque lute

“After re-entrant tuning was introduced in late 16th-century Florence, more musicians began experimenting with new tunings, especially in France. These experiments were to change the resonance and the sonority, however, not the volume. There’s so many scordatura tunings – about 80 were in use. Each one has its own special color and resonance that sounds utterly unlike the other tunings. You could transcribe the music for one tuning and play it in another tuning, but it sounds completely different. It would be like changing spices in a recipe; it would completely change the results. Playing 17th-century French music is rather difficult because of all these different tunings. Eventually, in the second half of the 17th century, the French, though particularly the Germans, settled on a tuning that’s a d minor chord. So the open strings, starting from the top, are tuned F-D-A-F-D-A, and then you get an octave of diatonically tuned bass strings tuned according to the key you’re playing. That’s the instrument we call the “baroque” lute today that Bach wrote for and the great virtuoso Sylvius Leopold Weiss wrote for.”

Are there any good solo lute parts in large, concerted works?

The Lute Player, Caravaggio, 1596

“It’s very common in the 18th century in Germany and Austria to have a very special aria with a lute obbligato in it. There’s a fantastic archlute obbligato that Handel wrote in his cantata Clori, Tirsi, Fileno which was obviously a show-piece for a lute player at the time. Pieces like this are very expressive, very intimate, they have a special color that sets up a real contrast from all of the agitation and the drama that’s happening on either side of that aria.”

What can the lute do that other instruments can’t?

The Duet: A Self Portrait of The Artist with his Wife, Judith Leyster, Probably Their Marriage Portrait, Jan Miense Molenaer, c. 1640

“Musical instruments have their own personality, their own spectrum of colors which make them distinctive from other instruments. For instance, you can certainly play the music of Dowland on the classical guitar, and many people do. It can be done very sensitively and very stylishly if you understand the style and the performance practice. Because the guitar has relatively thick strings and a relatively thick soundboard, the basic sound profile of the classical guitar is much darker than the lute and less transparent. It’s the transparency and clarity of the lute that give it the distinctive flavor it has. That’s what makes it ideal for contrapuntal music – you can hear all the voices so distinctly and so clearly.

“Because of the low tension of the string and the thickness of the soundboard, you have a quick attack and decay on the lute. The lute doesn’t sustain as much on the guitar, which is a great benefit when you’re playing fast music. Very fast runs and very intricate passage benefit from an instrument that speaks quickly and gets out of the way quickly. Then, you can hear the articulation of the individual notes easily. In many respects, you can compare the difference to a Viennese fortepiano that Mozart would’ve played on and a modern Steinway. I always encourage people to stop thinking in terms of progress and improvement. Instruments are not like computers. You’re not comparing the speed or the number of tasks it can do simultaneously. It’s about the qualities. If you get the right instrument for the right repertoire, you almost always find the voice of the music in a clearer and more vivid way than if you play it on a different instrument.”

To learn about Paul O’Dette’s upcoming performance with the Segovia Classical Guitar Series at Northwestern University, visit Northwestern’s website.