Tony and Drama Desk Award-Winning stage director Bartlett Sher

“Opera is deeply satisfying in a way that Shakespeare cannot be,” stage director Barlett Sher said backstage at Lyric Opera of Chicago during rehearsals for Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette.

Equally at home directing plays, musicals, and operas, Sher has received countless awards and nominations for his work. His 2015 revival of The King and I was nominated for 9 Tony Awards and received 5.

Having directed more than half of the Bard’s 37 plays and many of their operatic adaptions, who better to explain Shakespeare in the opera house than Sher? He described what makes telling Shakespeare’s stories in music so unique, his most and least favorite operatic adaptions of Shakespeare, and what Shakespearean operas are on his bucket list to direct.

When comparing any Shakespeare play to an operatic adaption, Sher reminds us that, “They’re different iterations of the same story. What opera brings to Shakespeare is something Shakespeare cannot do. It has a different scale. It has a depth in the sound. It’s the sound of falling in love or the sound of heartbreak. That’s what makes opera so extraordinary.”

In some ways, Sher finds telling Shakespeare’s stories easier in the opera house. “It’s different when you have the support of music. Otherwise, you’re just an actor who has to pull the audience through all of that, and it’s really hard. Opera is deeply satisfying in a way that Shakespeare cannot be. Some people think it’s better than Shakespeare. And of course, there are some things that are better.”

On the other hand, Sher says, “There are things that Shakespeare can do that opera can’t. When you’re in the middle of a Shakespeare play, and you’re watching struggles unfold, and you see the structural intelligence, the capacity to create great characters, the depth of language, you have another thing.

“You can be in the middle of working on an opera, and you turn to the original Shakespeare, and you see there’s so much packed into a speech that you don’t see in the opera. But you look at the opera and you think, ‘Hey, this is still pretty good. You don’t need to see that – you’re still getting a similar experience.’”

Some of the most memorable Shakespearean operas, perhaps, were created during the 19th century. Translations of the original plays became more widely available and composers saw incredible potential for adaption in the opera house. Here’s a look at some of Sher’s most and least favorites, and a glance at what’s on his bucket list of shows to direct.

Ot(h)ello

One of the earliest major settings of Shakespeare in the 19th century is Rossini’s Otello. The opera was adapted from a French translation of Shakespeare’s original by Jean-François Ducis, which incorporated dramaturgical elements from contemporary theatrical conventions. For example, Desdemona’s handkerchief, mentioned over 30 times in the original play and central to both the work’s plot and symbolism, is replaced with a letter.

An early criticism of Rossini’s opera by G.B. Shaw explains why Shakespeare’s masterpieces were perfect for the opera house. Shaw said, “Instead of Otello being an Italian opera written in the style of Shakespeare, Othello is a play written by Shakespeare in the style of Italian opera.” Indeed, the characters and stories in Shakespeare are so grand and so grotesque that they are perfect to explore.

Aleksandrs Antonenko in the title role and Sonya Yoncheva as Desdemona in Verdi’s Otello (Photo: by Ken Howard/ Metropolitan Opera)

But Sher’s favorite operatic adaption of Othello is by Verdi. “I’m so thrilled that Verdi did an opera based on Othello so that now I can do both. But I wouldn’t compare them. They’re extremely different.”

“It’s interesting what Verdi did with Otello,” he continued. “He dispenses with the first act and it makes the character of Otello hard to play. It doesn’t make Desdemona hard to play, because her struggle is resolved by the end even though it is quite complicated. The full opera? It’s really hard to get right. You need a Domingo kind of star to set up the stature of the title character. It’s not all entirely laid out for you the way it could be in the play, and even in the original Shakespeare it is hard.”

The opera is successful, Sher believes, because of the librettist. “It really takes a Boito to do a play like Othello justice. Having built new musicals I know that it always comes down to the book writer. The composer and the musicians are there to give you what you need. It’s really the book writer who provides you with the appropriate structure to hang what you need onto it.”

Romeo and Juliet

There are at least 20 operatic adaptions of Romeo and Juliet, to say nothing of Bernstein’s West Side Story. The earliest examples date from the late 18th century. While Romeo and Juliet may be, understandably, one of the most popular of Shakespeare’s plays that has been treated operatically, Sher reminds us, “No one has ever set it word for word, the language is just too dense.”

Some of the most famous speeches in Shakespeare’s original tragedy are absent in Gounod’s opera, for example. “The balcony scene is a series of sonnets. It is exquisite, language-wise. But I don’t know how you’d set that to music. Music moves at a different speed than language. Gounod’s balcony scene is totally different because he just captures the thoughts he needs to, and the way he breaks it up is different.”

Gounod’s Romeo and Juliet at Lyric Opera of Chicago, with Joseph Calleja as Romeo and Susanna Phillips as Juliet (Photo: Todd Rosenberg)

Still Gounod stays relatively close to Shakespeare’s original. “It’s structurally basically the same,” Sher said, “though he compresses the first two acts into the opening party scene. But I enjoy that because in a single scene the different groups come in, then Juliette arrives, and next thing you know, they’ve fallen in love and there’s a fight that smashes up the party.”

Though some might gasp at the idea of changing Shakespeare, Sher reminds us that Gonoud and his collaborators “didn’t think too hard about it. They were very brave, and they took a risk by jamming everything together. Gounod is forced to make some musical transitions that are really incredible as a result.”

Another major difference between Gounod and Shakespeare was the times in which they lived and the values that their works reflect. “Shakespeare is dealing with a classic struggle in the Renaissance: the expression of individual love versus the wants and needs of a parent or the state,” Sher said.

“That’s not such a big worry on the part of Gounod. I think Gounod is more interested in the transcendent power of love. You have these ecstatic duets which are trying to reach some other place in expressing love. Shakespeare stays very strongly in the tragic circumstances, in the struggle between the families, and the punishment of the father.”

“To be or not to be” an opera, that is the question

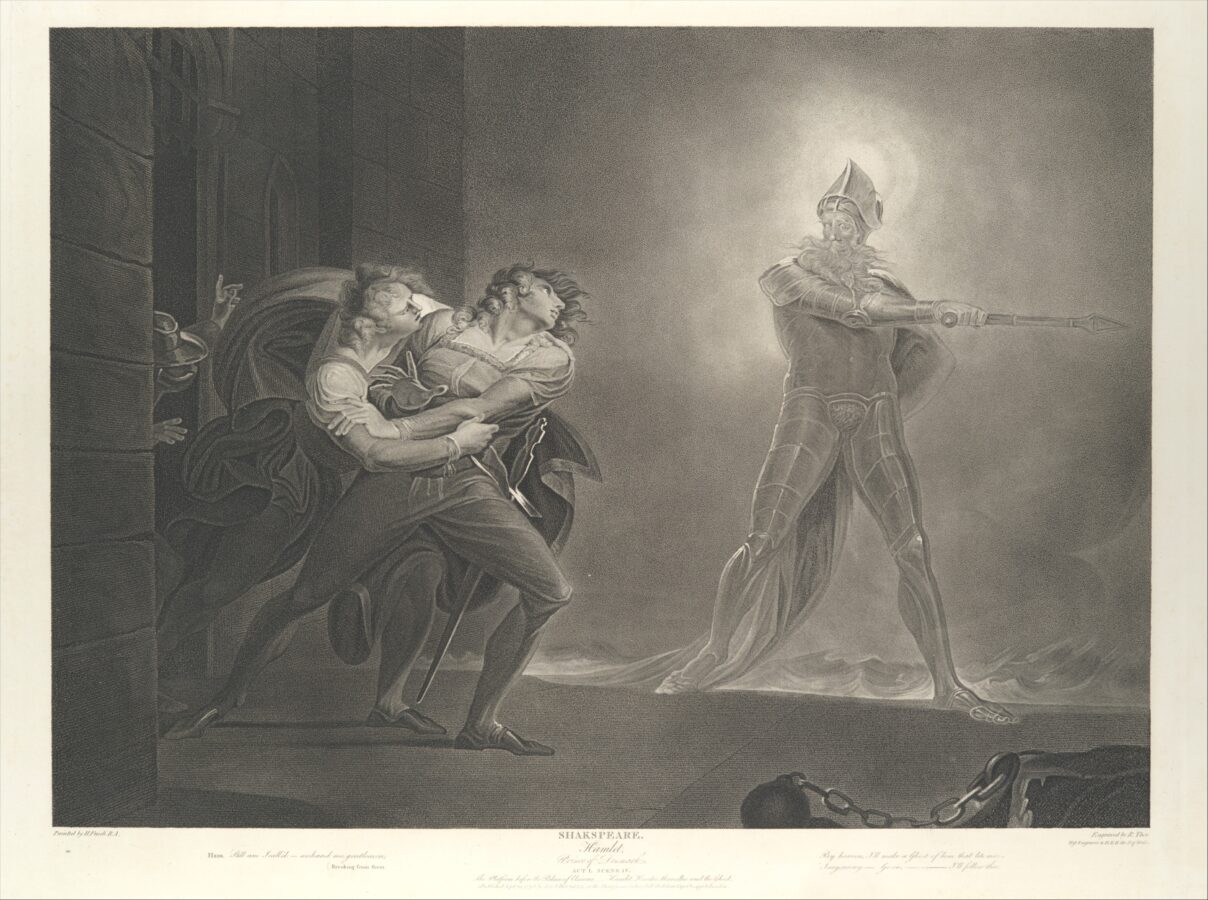

While Hamlet may be one of Shakespeare’s most well-known plays, none of its operatic adaptions are particularly popular today.

The French composer Ambroise Thomas tried his hand at adapting Hamlet in the 19th century. Like many other Shakespearean operas, Thomas’s Hamlet is an adaptation of an adaptation. The libretto, by Michel Carré and Jules Barbier, was based on a French play, Hamlet, prince de Danemark, by Paul Meurice and Alexandre Dumas.

The French composer Ambroise Thomas tried his hand at adapting Hamlet in the 19th century. Like many other Shakespearean operas, Thomas’s Hamlet is an adaptation of an adaptation. The libretto, by Michel Carré and Jules Barbier, was based on a French play, Hamlet, prince de Danemark, by Paul Meurice and Alexandre Dumas.

Thomas’s opera was successful when it premiered, but has not been performed often in modern revival. Curiously, few besides Gasparini and Thomas have turned to what some consider Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy for operatic inspiration.

“Hamlet is very hard to set well to music,” Sher explained, “because it’s punctuated by eight soliloquies that are incredibly complex even in the way they are set up to allow characters to pause and reflect. Opera isn’t like that. You can’t pause. Opera likes to keep moving.”

The Scottish Play

“I think The Scottish Play and The Scottish Opera are great,” Sher said, referring to Macbeth. “But I find that play extremely unpleasant and difficult. Structurally, it’s kind of thrown together by Shakespeare and I think it doesn’t work as well. The only one that’s really structurally sound is Kurosawa’s The Throne of Blood, which is a film set in feudal Japan.”

“I think The Scottish Play and The Scottish Opera are great,” Sher said, referring to Macbeth. “But I find that play extremely unpleasant and difficult. Structurally, it’s kind of thrown together by Shakespeare and I think it doesn’t work as well. The only one that’s really structurally sound is Kurosawa’s The Throne of Blood, which is a film set in feudal Japan.”

Sher’s Shakespearean Bucket List

Though Sher has directed his fair share of Shakespeare in the opera house, there are still some works he is eager to perform.

“Verdi’s Falstaff is one I am dying to do – I really wanna do Falstaff! I saw a production at Welsh National Opera that was so incredibly good,” he said. “It felt so contemporary but so ancient at the same time. I was quite moved by it.”

Falstaff does not directly adapt any single Shakespeare play but instead combines elements of The Merry Wives of Windsor with the Henry IV plays. The last of Verdi’s operas, it was his second comedy.

Craig Colclough as Pistol, Bryn Terfel as Sir John Falstaff and Michael Colvin as Bardolph in Falstaff, The Royal Opera (Photo: Royal Opera House / Catherine Ashmore)

There’s another Shakespearean comedy Sher would like to stage at the opera. “I love A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and I’d love to do Britten’s opera,” he said enthusiastically.

Of course, there are also many Shakespeare plays that have not yet been musically set. As someone who has created new works himself, Sher mused over what play he would select to adapt into an opera.

“I would stay away from the great tragedies, King Lear and Hamlet are a little too complicated. The Scottish Play and Othello are taken and nobody should compete with those! I think the romances are a good idea for the right kind of composer. The Tempest has been done enough. Winter’s Tale might be good, because there’s a great opportunity there because of the relationships in that story.”

So, with those plays out of the running, what would Sher select?

“I would probably pick Titus Andronicus,” Sher said excitedly. “What’s interesting about the romances is that there’s an emotional quality but also a lightness, so there’s a magic in those stories. But for the pure powerful richness, Titus would be awesome. I’ve directed it twice – it’s one of my favorite shows ever – and used music in it. It can be updated well, like Julie Taymor did, and put it in a new context. It’s kind of like early punk rock Shakespeare. The prose is very clear and not as complex. When you get to the late plays, the language is almost like listening to Miles Davis the way he packs things in there.”

WFMT broadcasts Gounod’s adaptation of Romeo and Juliet from Lyric Opera in Chicago on Monday, Feburary 22, 2016 at 7:15 pm central. Don’t forget to tune in, and be sure to tell us your favorite operatic adaptions of Shakespeare in the comments below.