Conductor Harry Bicket (Photo: Dario Acosta, courtesy of Santa Fe Opera)

Harry Bicket is the artistic director of the English Concert, one of the world’s preeminent baroque orchestras. Bicket also regularly conducts modern orchestras at the world’s greatest opera houses, and is chief conductor of the Santa Fe Opera. “I’ll do things with a modern orchestra I’d never do with the English Concert, and that’s fine,” Bicket said in his dressing room at Lyric Opera of Chicago during its run of Gluck’s Orphée et Eurydice.

Why? We can hear how musicians change their techniques and styles year-to-year in the popular music of today. Naturally, the same techniques used to play Bach differ from those used to play Britten. Musicians use the right techniques for the particular style of music they are playing, and a conductor’s guidance can be key.

“You have to be careful not to undermine the orchestra. But also in a very short space of time, you want them to sound good.” Bicket shared what’s in his “little box of tricks” to help musicians in modern orchestras sound period perfect.

“Real beauty is only ever achieved on the edge of a cliff.”

It’s drilled into modern orchestras that you have to play exactly the same as each other, you have to do exactly what the principal is showing you, and that goes to the top of the orchestra, and that’s how you all play together. I undermine all of that. I want musicians to dare, take risks. Harnoncourt used to say, “Real beauty is only ever achieved on the edge of a cliff.” I kind of buy into that. If we don’t dare, we end up just being pretty. Pretty for me isn’t very interesting in its self.

You have to listen. Every time you play a piece, you should have fun with it. But that requires a huge leap of faith. I try to give players permission to play things differently every night. There should be a sense of rediscovery every time we play – provided you’ve given them the little box of tricks.

Younger players have heard period instruments, they may have even held one or played one. It used to be this weird cult of people who couldn’t play modern instruments, or at least that’s the criticism, though in some cases, it’s true. But when people first started playing these instruments, no one knew. You were just experimenting. So the technical level sometimes wasn’t that high. But I don’t think that’s true anymore. I think you can hear really, really fine playing.

Heidi Stober as La Folie in a production of Rameau's Platée at Santa Fe Opera with Harry Bicket conducting (Photo: Ken Howard, courtesy of Santa Fe Opera)

Orchestras should speak, not just sing

Modern players often want to know, “Is this movement on the string or off the string?” I say, “It’s both and neither. Name me a note.” It’s like speech. Some vowels are longer than others. Some words have shorter vowels and longer consonants. If you have to analyze every sentence, you couldn’t do it.

The big thing I try to explain is that the idea of evenness in the 18th century was an anathema. No one thought music should be even, everyone thought music should be like speech. If you have singers on stage articulating text, with all the very tiny little changes – different vowels, consonants, double consonants, elisions – and all we’re doing in the pit is “wah-wah-wah,” it’s going to make for a very long evening. What we need to do in the pit is be more like the singers on stage. We have to speak. Orchestras are always being asked to sing, which is great. But they should also speak.

“It’s like patting your head and rubbing your stomach”

All of the principles to play in style are really simple and logical. A lot of players don’t know why they do certain stuff. For example, I was doing Handel’s Alcina with the Santa Fe Opera, and the orchestra is very good at this stuff. But every time we got to a trill at a cadence, they shoot their way through the bow and it would give this huge accent. At first I suggested we do a slower trill so that it doesn’t sound like a squirrel scratching its ear. I said, “Let’s do a softer trill with a longer appoggiatura – just ease your way, it’s a lovesick trill, a cantabile trill, it’s not a virtuosic one.” So they do that but they still shoot their way through the bow, and I said, “Why are you doing that?” The leader laughed and said, “You know that’s a good question. We just see a trill and that’s what happens.” (Watch an excerpt from Alcina at Santa Fe Opera below.)

Sometimes even if you get one half of your brain to understand something, it’s hard to program the other half. It’s like patting your head and rubbing your stomach. They really, really had to practice how to do a slow trill with your left hand and a slow bow with your right. It’s not a difficult thing to do. These are people who play Prokofiev concerti, but they find this very hard.

When I first worked at the Metropolitan Opera, I spent about 10 minutes trying to get them to do a cadence, just a dominant chord going to a tonic chord, starting with an up bow and going to a down bow, but not making a break in between. The Met Orchestra, one of the best orchestras in the world, couldn’t do it. They said, “We could slur it.” And I said, “No! It’s not the same gesture! It’s a two-syllable word. You don’t make a break between the first syllable and the second syllable.”

Before rehearsals start, mark your part

I was a violinist at one point. And over the years, I know what I want. There are some things are pretty negotiable. But before rehearsals start, I make sure orchestral parts are marked – not within an inch of their lives, but essential things like certain bowings. Bowings can define the musical gestures I am trying to achieve. Some bowings can be quite antithetical to the way modern players are taught to play. But rather than have a long conversation about that in the beginning, I find that if it’s just in the part, they will do it.

Conductor Harry Bicket

Now they’ll do it and it won’t sound very good, and you have to remember that’s always going to be the case. But then you start talking about what the gesture is and why it’s marked in that way, and I find that’s a good short cut. Otherwise, you end up talking too much. Orchestras complain that you either talk too much or you don’t have anything to say. No one knows how to find that middle ground.

Once you solve one problem it can often unearth another. Bit by bit, it’s only about 7 or 8 ideas that you need to know about bowing. As soon as you understand why a kind of bowing is in your part in one movement, you can apply it to the rest of the piece. But in the beginning, it’s very slow, especially if it’s the first time I’ve worked with an orchestra.

String players: play in the middle of the bow

Modern players are always asked to play very evenly so your upbow sounds the same as your downbow. In Handel, for example, when we have something like a French overture with lots of dotting, any modern player would want to do what we call “hook it,” meaning playing two notes per bow, so it’s like “DA, duh DA, duh DA, duh DA.” (Hear the English Concert play these rhythms in the overture to Handel’s Samson with Bicket conducting below.)

Because you have a heavy bow, it’s less effort. And if you’re playing a four-hour opera, you have to conserve your energy. But that was never a known practice in the 18th century. So what we ask them to do is always “re-take,” so the first note in a dotted rhythm gets a sort of “szwoom!” So it becomes, “szwoomDA, duh DA, duh DA, duh DA.” It doesn’t feel so flat.

This requires you to always play in the middle of the bow. A lot of modern players naturally go towards the point of the bow because that feels lighter. When notes are slurred into each other, if you play that with a baroque bow, you go through the bow on a down bow, and naturally the second note is weaker, because you’re going to a part of the bow that’s less strong.

But that’s not true on a modern bow, so you have to do a bit of a diminuendo on a slur. Then you’re on a part of the bow where you’re worried about if you use too much bow, which is another problem, you have to get back up, so the next note gets a sudden accent in the middle of the phrase.

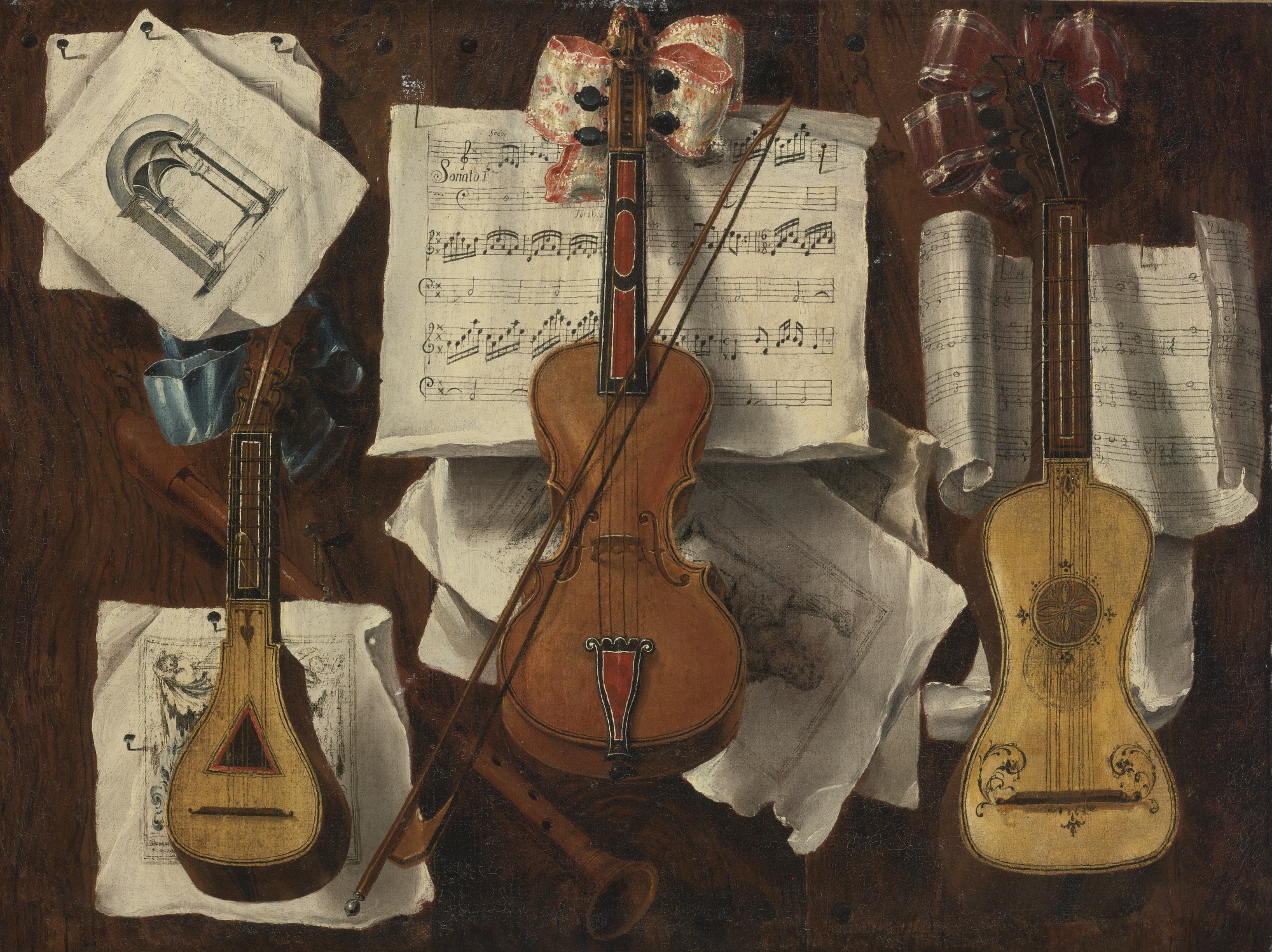

Trompe l'oeil still life. Sebastiano Lazzari (fl. Verona, 2nd half of 18th century)

String players: use vibrato to add variety

Modern orchestras are probably always just waiting for me to saying something about vibrato. The thing about vibrato is that of course they used vibrato in the 18th century. It’s nonsense to assume people played without vibrato, but it was used very much as one of the many tools that one had to color. But it was not the only one. The difference now is that modern players are not only taught to play evenly with the bow through the phrase, but also to play with vibrato on every single note so that it just becomes part of the sound, and that creates less variety. (Hear players and singers use vibrato to add variety in a performance of Handel's Ariodante led by Harry Bicket at Carnegie Hall below.)

Someone even earlier than in the 18th century (it may have been Praetorius) likened the violin to the body and the bow to the soul. I think it’s a very useful metaphor because the instrument in your left hand is simply the tool by which you create the music with your right. For many modern players, it’s the other way around: the bow is what makes the sound, and the left hand creates the emotion. So as soon as one says, “Let’s cut the vibrato out and add more here and there later,” everything ends of sounding like a high school orchestra because you’ve taken the anchor away from a lot of players.

So if you’re going to take vibrato out, you have to make sure you replace it with a much more varied and expressive right arm so you get lots of different colors not by your left hand but by how you gesture with your right. This exposes two things: right arm technique, which is sometimes not always as good as people think it is, and intonation. A lot of people don’t really play in tune. If you vibrate enough, people can’t tell when you’re not perfectly in tune. It forces you to decide, where is that note.

String players: stay low on the neck

Vibrato can also create resonance and help sound project. But without vibrato, we can achieve this by using as many open strings as possible as well as lots of low positions on the neck. The lower the position, the longer the string, it’s not quite so stopped, so you get more resonance. It’s true more on gut strings than metal strings, but it’s still a very useful exercise. That throws people out because most people finger in a particular way – whatever is the most efficient, rather than what’s going to give them the best articulation.

String players: learn to love open strings

A lot of players are told not to use open strings unless it’s a low G and you have no choice. When I’m encouraging players to use open strings it’s always a shock, so they always play them rather gingerly. But in the 18th century, the instruments weren’t even and the composers want certain notes to spring out from the texture. They want them to be louder and more resonant than the other notes. That goes against our modern idea of everything being very even.

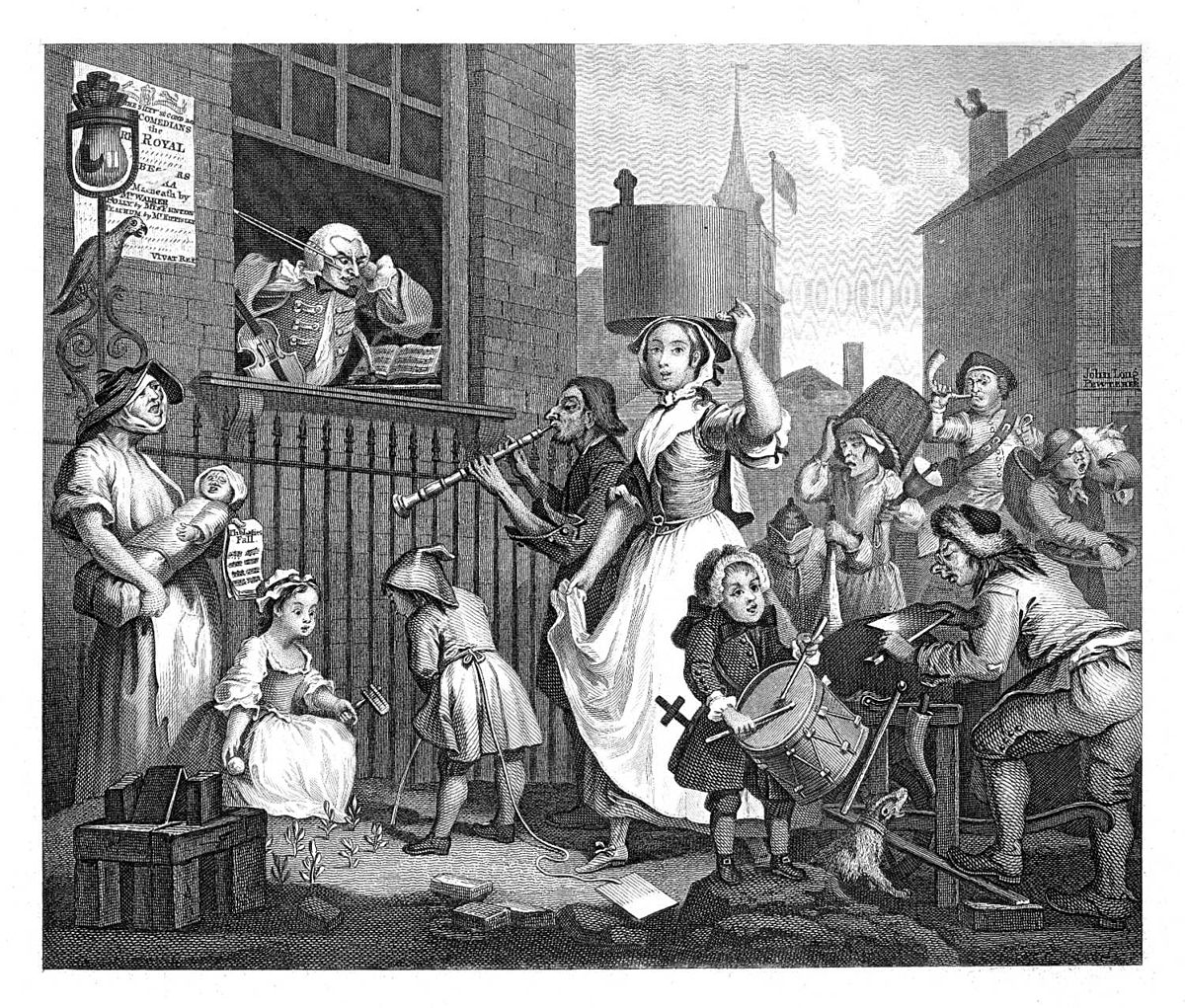

The Enraged Musician. William Hogarth. 1741.

Woodwinds: a philosophical approach to playing

With the evolution of oboes, bassoons, and even flutes for that matter, everyone talks about change resulting because they needed to sound louder because writing for these instruments became more soloistic, so they needed to be heard over the orchestra. Some of that is true. But one of the main things they wanted to do is iron out inconsistency.

You don’t have very many keys on a baroque flute or oboe; everything is done by the holes. You have some choice in how you’ll get the same note from different fingerings, but some notes will speak louder than others and some notes don’t play in tune as well as the others. But composers knew that and composed to capitalize on that unevenness. (Hear how Handel utilized the unique sound of the bassoon in "Scerza infida" from Ariodante below.)

Oboes from the 18th century are much woodier and darker and softer. They’re very, very good at blending with strings. That’s why there are many passages in which the oboes double the strings. In fact, in the 18th century, many string players doubled playing oboe and violin.

It’s difficult for the modern oboe to blend with the violin because of structural differences. It helps to play a little less loudly. Some players can achieve a certain sound with a change of reed. But these instruments aren’t designed to play a certain way, so I can’t ask the impossible.

What I can do is encourage a philosophical shift in how they approach their parts: be a member of that section. You can’t just play your part as you would in La bohème. If you’re an oboist playing Handel, you have to literally watch the strings so that if the strings do a retake and you’re playing in unison, you have to do the retake with them. That’s something a lot of modern woodwinds aren’t used to doing, because they’re used to playing as a unit: a wind choir, if you like. The idea of minutely matching the gestures of a string player can be new. Modern players often assume everything is a solo. But you have to realize when you’re a soloist and when you’re not.

The powerhouse: the bass

All baroque music is really, in the best way, driven from the bass upwards. The bass is the rhythm section. It’s the powerhouse of what happens above. Often bass lines in Gluck and Handel don’t look like very much. It’s often quite basic harmonic structure. You could get five bars of the same note. The bass parts I don’t mark up quite so much, because if I marked them the way I wanted to, there would just be so much information on the page. I’m not sure you can even annotate half of it.

Alek Shrader (Oronte) and Wise Fool New Mexico in Alcina at Santa Fe Opera (Photo: Ken Howard, courtesy of Santa Fe Opera)

Singing in style

People don’t like being asked to sing in a way that they find is challenging for them. If you’re looking to find a beautiful, well-mixed, blended sound, particularly in homophonic music (which a lot of Gluck’s choral music is), someone whose natural instrument is more suited for Verdi… you’re asking someone to drive a Ferrari 5 miles an hour down a little country road. You know, Ferraris don’t enjoy that: it’s not good for the engine. I can understand that it’s a challenge for them. But for me, a challenge is also an opportunity.