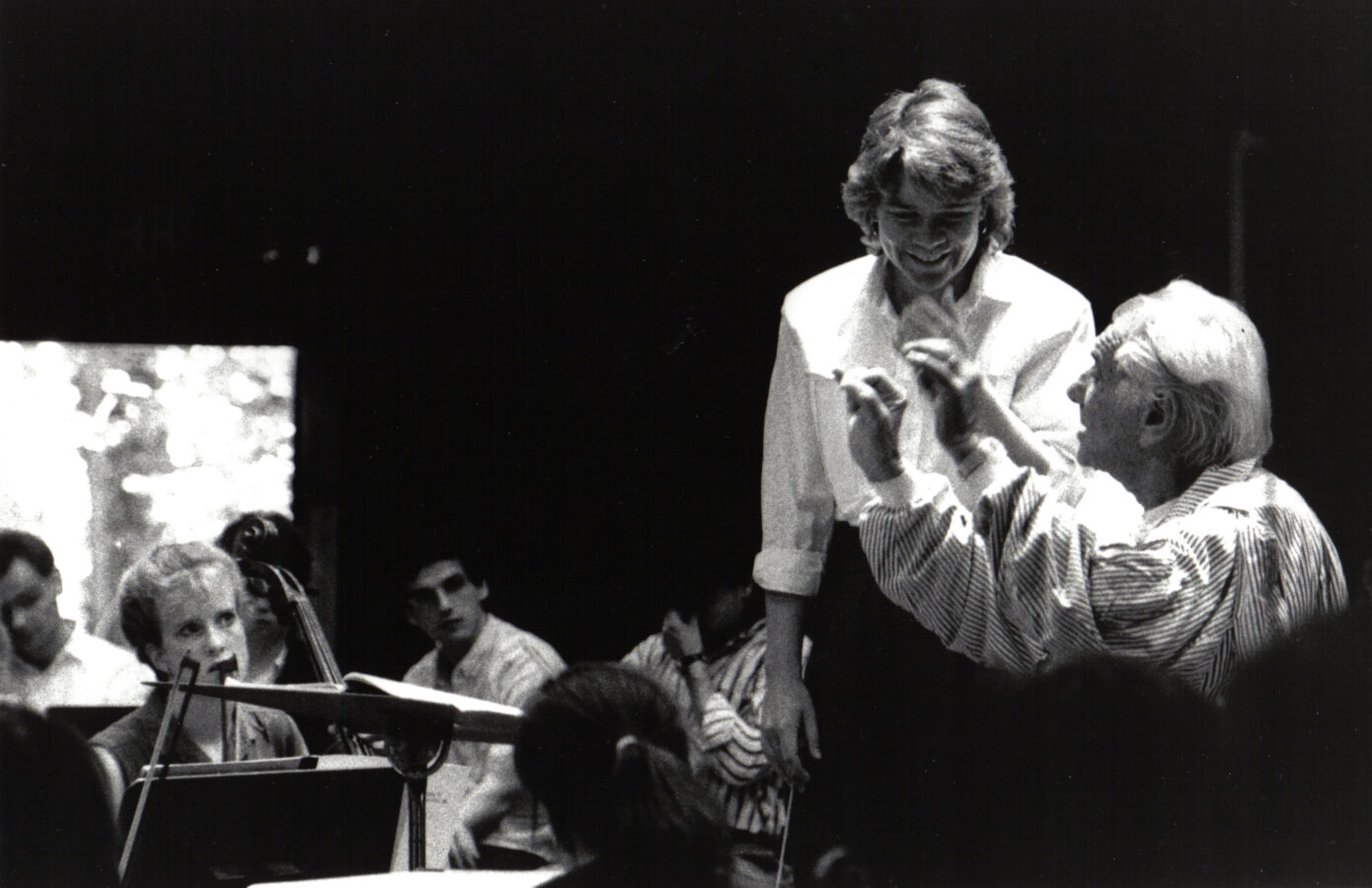

Marin Alsop with her mentor, Leonard Bernstein (Photo: Walter Scott)

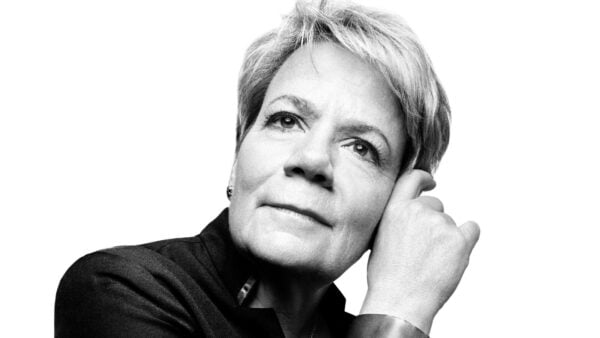

As the world celebrates the centennial of Leonard Bernstein’s birth, one of his protégés, conductor Marin Alsop has a busy schedule conducting his works around the world. During rehearsals with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for performances of Bernstein’s MASS at the Ravinia Festival, Alsop spoke about some of the most important lessons she learned from her mentor about music and about life.

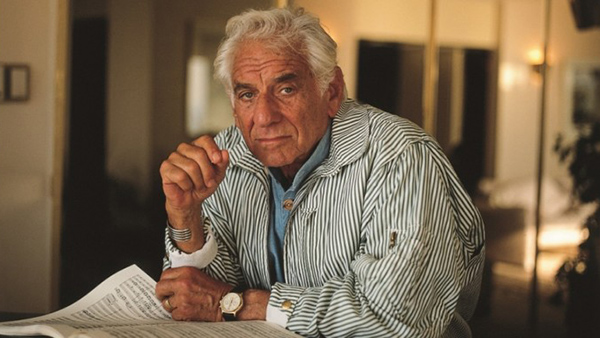

I first fell in love with Leonard Bernstein when I was nine years old, and my dad took me to a Young People’s Concert performed by the New York Philharmonic. I saw this guy come out and he started talking to the audience, to me, and he was sharing how excited he was about the music. Then when he conducted, he jumped around and was kind of crazy. I turned to my dad that day and said, “That’s what I want to do, I want to be a conductor.”

That man was Leonard Bernstein.

In my room growing up I had two posters; one was of the Beatles and the other, which was bigger, was of Leonard Bernstein. He occupied a big space in my heart and in my mind. Getting to study with Leonard Bernstein was beyond a dream come true. Having a hero is a tricky thing: not many people have heroes I don’t think, and I was always afraid that meeting him would somehow take away from my imagination of what he was about. But when I met him, he exceeded all of my expectations exponentially. He was intensely generous and affectionate and warm.

Leonard Bernstein taught me so much, not just about music, but about living as a citizen of the world. Whether one agreed with his politics or positions, watching him stand up for what he believed in was so inspiring and set such a great example for me that I started developing a feeling for the kind of person I wanted to be as well.

As far as music goes, Bernstein was able to articulate the role of the conductor very concisely. He always talked about how the primary and almost singular responsibility of the conductor is to be the messenger of the composer.

Bernstein was one of the greatest storytellers ever. I remember him coming to Tanglewood, and I had already rehearsed the orchestra on a Hindemith piece. He came in and he asked the orchestra if I had told them the story of this piece, which of course I had, and all the musicians said, “No, no, she didn’t tell us,” because they wanted him to tell the story. I saw that over and over with seasoned musicians because every story he told was a teaching story. First of all, he was highly entertaining, but there was always an incredible moral. Music, I think, for Leonard Bernstein was just an extension of storytelling. It was storytelling with a language that transcends spoken language. It was storytelling, in a way, that could reach a lot more people.

When music doesn’t have a specific narrative or a program to it, I think Bernstein would often make up the story. It would be a story of how he felt the composer was motivating every note in the piece. For me, the great thing is that I believe there is a story to every piece, but I don’t believe it’s necessarily prescribed. If everyone left a concert I conducted feeling that they had heard a different story from the person sitting next to them, I would be very happy. Then I would really be reaching people on many different levels, not just in one prescribed story line. I’ve heard people say that listening to a piece of music has given them some sense of understanding, or of closure, some comfort, and I realize that music does have that capacity. It speaks to each person differently, and I totally respect and embrace it.

I think that’s a fundamental responsibility that we as conductors have, to commit wholly to whatever piece we’re conducting. If there’s a piece I’m conducting with which I don’t feel an immediate connection, I think those pieces require more time, and more effort, and more energy rather than less. Often those pieces end up becoming my best friends in the long run. It’s very much like relationships with people; you think you don’t really care for this person, but you somehow get stuck talking to them many times over dinner, and pretty soon you realize there’s a lot more to this person than I thought. Art is like that as well; even if at first you don’t love it, if it’s great art you can always find its value, and try to get to the essence of what’s important in it.

Marin Alsop with her mentor, Leonard Bernstein (Photo: Walter Scott)

Being around Bernstein and watching him made a big impression on me. He so loved working with young people and young orchestras at Tanglewood and at Schleswig Holstein where I first met him. He never spoke down to children, he spoke to them as just smaller adults. His expectation was that every child could understand what he was saying, and every child did understand what he was saying. I think we do children a terrible disservice by lowering the bar. The higher you put the bar, the more children will achieve. Every child seems to be born a genius and we gradually suck that out of them as a society, and coming to parenting later in life, I realize that my son could do anything, it’s just a matter of creating the landscape for him to excel.

Every child, I believe, should have access to art. Art and, particularly from my perspective, music, is a way to express oneself. I remember playing the violin as a kid, and unlike mathematics or spelling where you’re right or wrong, when I played the violin I was always right. I got so much confidence and validation from that experience. Studying the violin gave me incredible skills that I’ve used and benefited from my entire life: discipline; understanding that it really takes practice, every day, applying oneself to succeed; when you play in a ensemble to have to listen to other people, but then you have to step out and take the lead. All of these skills, I think, should be available for every child. Often it’s an economic barrier that inhibits them from having that same access.

For me, trying to overcome that in Baltimore, which is a city that struggles in terms of economic equality, creating a landscape for less privileged kids seemed like a natural thing to do. Ten years ago we at the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra started a program called OrchKids with 30 young people, and now we have about 1,500 playing musical instruments, and they’re amazing. It really is a testament to the talent that these young people have innately. It’s not that they’re all going to be professional musicians, but they all see themselves with futures filled with possibility. That’s what it should be about, and that’s certainly what Bernstein stood for.

Bernstein said that our response to violence will be to make music more intensely. I think in the world in which we live, which can be quite violent, that’s a beautiful way to think about things. If we invest ourselves in creating beauty as opposed to destroying each other, maybe the outcome will be what we all hope for.