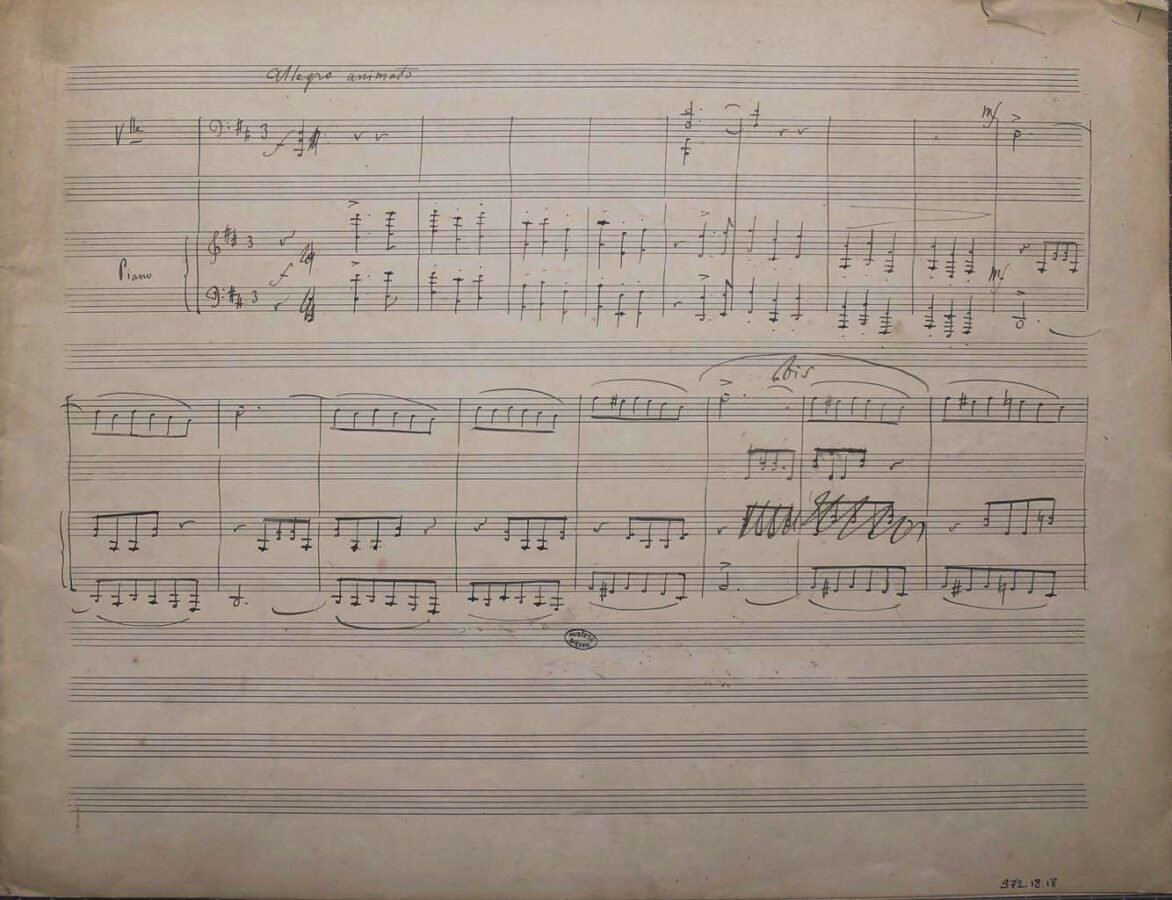

A page of the manuscript (courtesy of Juliette Herlin) with the work's composer (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

It’s not every day an artist can re-discover a piece of music by a master from the Romantic era. Yet this was the enviable privilege of cellist Juliette Herlin, who in 2017 gave one of the first performances since 1919 of a lost cello sonata by Camille Saint-Saëns.

Cellist Juliette Herlin (Photo: Jiyang Chen)

To say that Herlin was raised in a musical household is an understatement: her mother played piano, and her sister played violin. She shares, “I actually wanted to start [playing cello] when I was 3-½-years-old, but I was told I was too small… so I had to wait a year.” She had the additional perk of growing up in a household not only musical but also musicological: her father, Denis, is a musicologist specializing in French music, Debussy in particular.

In 2015 and 2016, Denis Herlin was working with a publisher to release a collection of Saint-Saëns’ complete works. During the project, he uncovered a Saint-Saëns work never before published — a cello sonata. The manuscript, found with other papers from Saint-Saëns’ secretary, was incomplete, containing only the first two movements. “Just a few pages and really not a lot of information about that,” Juliette recounts. “My father actually had to use the type of paper to date the sonata [between 1918 and 1919], and that’s how we know that it’s the third sonata.”

As for the last movements? “It’s still a bit of a mystery,” Juliette explains. There is evidence that the piece was performed complete in 1919, but other manuscripts have yet to surface. It’s possible that what Denis Herlin uncovered was a draft. “What’s a little bit odd is that the manuscript actually stops quite abruptly, in the middle of a page, rather than at the bottom of one page,” the cellist explains. Could it have been writer’s block? This theory seems plausible — in an introduction, Denis Herlin cites letters that show the composer’s frustration with the piece.

A page of the manuscript (courtesy of Juliette Herlin)

“When my father told me about the piece, I was very curious, of course,” Juliette recalls. “I was able to look at the manuscript, and I actually really loved the piece. I loved the simplicity of its texture, and I thought it was just a very interesting work. And the more I was playing it, the more I was working on it, the more I really thought it was fantastic.”

Juliette Herlin and Kevin Ahfat's performance of the Saint-Saëns Cello Sonata at an April Dame Myra Hess concert was actually the Chicago premiere of the piece.

Saint-Saëns wrote for cello more than his contemporaries, but Juliette feels that this third and final sonata cello work bears a resemblance not to others for cello, but to his bassoon sonata, another late-period work.

“It’s interesting, a lot of composers’ works become more and more complex towards the end of their life. And for Saint-Saëns,” she observes, “I feel like he’s going towards simplicity. The sonata is very pure in terms of lines. I think what was really striking to me for this work was the wide range of contrast, colors of sound. There’s a lot of things that one could do with that.” Juliette describes the first movement as joyful and full of energy, and the second movement as more expressive and thematically richer.

Cellist Juliette Herlin and pianist Kevin Ahfat

Adding to the expansive creative possibilities is the fact that the manuscript had few dynamic markings, meaning that Juliette and her collaborator, pianist Kevin Ahfat, had to decide their own. “It was a really interesting process — very freeing and just very rich — because we would experiment and explore new interpretations all the time.”

This scenario seems like an artist’s dream — a clean slate with a highly expressive piece. Indeed, Juliette says, “Most of the time, you have a recording to refer to. This is almost a brand-new piece. You don’t have any other interpretations in your ear, any tradition.” No doubt this mystique piqued audiences’ interest, too. “People really seem to like the piece. Which was nice, because we didn’t exactly know what people would think about this performance of an older work.”

The experience of interpreting the piece has informed Juliette’s playing of other works — “I think that I try and apply the same process to other pieces. Meaning to always try to be as convincing as possible with musical ideas, to try always to keep that freshness, and to always go further, dig further, recreate, refresh.”

Her relationship with the piece has evolved over time, but it still holds a special place in her repertoire and in her career. She reflects, “It’s fun to play the sonata over different years, so I also see how much I’ve grown with it in a way."

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.