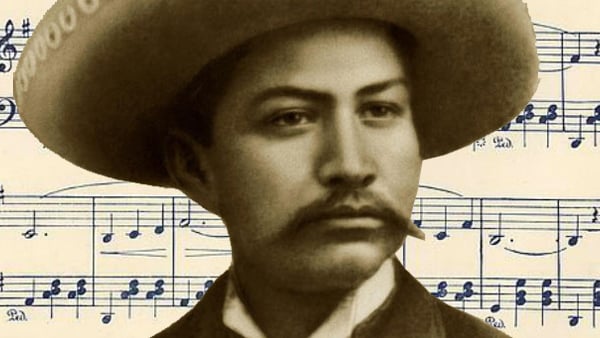

Portrait of composer Florence Price (Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville)

On June 15, 1933 the Chicago Symphony Orchestra presented a historic concert at the Auditorium Theatre. First on the program was a concert overture, “In Old Virginia,” by American John Powell. Afterward, the audience heard an aria from Berlioz’s L'enfance du Christ sung by Roland Hayes, a tenor and composer born to former slaves in Curryville, Georgia. Hayes also performed two African American spirituals, including one he arranged himself, and a work by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, whose mother and father were from England and Sierra Leon respectively.

That evening, audiences at the Auditorium also heard the world premiere of Florence Price’s Symphony in E Minor. While any world-premiere performance is a noteworthy event, this occasion marked the first time that a major American orchestra had performed a symphony by a woman of color. A review in the Chicago Daily News called it “a faultless work, a work that speaks its own message with restraint and yet with passion… worthy of a place in the regular symphonic repertoire.”

Price must have been elated to share this program with her close friend and collaborator, Margaret Bonds, who performed as the piano soloist in Concertino, a work by Illinois native John Alden Carpenter. Bonds was also likely the pianist who performed the final piece on the program, Bamboula, by Coleridge-Taylor.

Price and Bonds continue to inspire musicians today, including pianist Samantha Ege, who presents a program of music by both women at Chicago’s Symphony Center on Thursday, April 12, 2018. Ege said, “As a pianist, I’ve always wondered how I fit in. At University, I felt like an anomaly. And it wasn’t until I discovered Florence Price that I realized I wasn’t. It’s a strange realization to have, because I knew I obviously wasn’t the first Black person in classical music. But with what I saw around me, it definitely felt like it.”

“Learning about Florence Price gave me so much strength and so much confidence in what I was doing. I always knew I wanted her to factor into my life in a more significant way, but I wasn’t sure how to go about that. But now I’m working on the music of Florence Price for my Ph.D. She’s a part of my journey, and I know that I belong, and I’ve found other people who were missing from my experiences growing up. I have a greater sense of myself and my role, as well.”

Margaret Bonds

One reason we know the names of Price and Bonds today is chance. Both women entered the Wanamaker Music Contest, sponsored by department store magnate Rodman Wanamaker. Price took home prizes in several of Wanamaker’s contests, including the top prize in a competition that awarded her $500 and the opportunity to have a composition performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. “He was a white person who basically felt pity towards African Americans,” Ege said. “But without that platform, we may not have heard Florence Price’s works.”

In discovering more about the music of Price, Ege has also learned that some of her success came because she was part of artistic communities, all part of the Chicago Black Renaissance, in which other women of color were pivotal players.

“When we highlight only a few figures,” Ege explained, “we isolate them from their communities. That kind of exceptionalism is not helpful; it continues to perpetuate this idea that there aren’t Black classical musicians or composers, that there’s only one or two great ones who come around once in a blue moon, but that’s not true at all.”

She is excited to share the stories of members of those communities which otherwise might be almost forgotten. Since Ege was born in Great Britain, is of Nigerian and Jamaican descent, and is now based in Singapore, she has relished the opportunity to dive into the archives at Chicago’s Center for Black Music Research to help tell these stories.

Irene Britton Smith (Courtesy Center for Black Music Research, Columbia College Chicago)

Though many music lovers may be familiar with the work of Margaret Bonds, they may not know that her mother, Estelle Bonds, was “a real pivotal figure in terms of welcoming musicians and empowering them, whether they needed a place to stay, or just needed to be in that kind of creative environment,” Ege said. “She seemed to be a key person creating this community for people.”

Ege has also been fascinated to explore the music of Irene Britton Smith, another Chicago native. Smith studied at the American Conservatory of Music, where she earned her bachelor’s degree, and DePaul University, where she earned a master’s. She also studied composition at the Juilliard School and took lessons with Nadia Boulanger.

Later in her life, she became involved with education and outreach at the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. “She was just very involved in the musical community in Chicago,” Ege said. “She’s an interesting person because I’ve come across her compositions, and they’re very well crafted, but she’s a very humble person, so she doesn’t quite convey how masterful she is as a composer through her own words.”

One composer whose work has been essential to Ege’s research is Nora Holt. “She was a real pioneer. She was a cofounder of the National Association of Negro Musicians, of which the Chicago Music Association was the first branch, in the early 1900s. Then she became the first Black person in the United States to get a master’s degree,” which she received in music from the Chicago Musical College.

Though most of Holt’s scores have not come down to us (at least not yet!), she did other essential work besides just making music to help African American musicians around the country. She wrote for the Chicago Defender, a daily Black newspaper, throughout the 1920s, and then for the New York Amsterdam News, a weekly paper that also published the writings of W.E.B. Du Bois, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. “She’s constantly documenting African American musical achievement, and without that, I wouldn’t have half the names I have right now.”

Portrait of Nora Holt by Carl Van Vechten

One reason some of these names have been, perhaps, near-forgotten is because of tension, then and now, between jazz and classical music. Ege notes that Maude Roberts George, a former president of the National Association of Negro Musicians, expressed frustrations that musicians like Duke Ellington were getting paid far more than composers like William Levi Dawson because of mainstream expectations to see Black musicians in a jazz context, rather than a classical music context.

“It’s not just about the music, there’s a real visual expectation when it comes to classical music,” Ege said. When introducing herself as a pianist even today, Ege lamented, “the assumption is that I’m a jazz musician.”

“That sort of tension also manifests in the ways that these composers aren’t connecting as much to jazz,” she explained. “George Gershwin is famous for taking on African American musical traditions, but he tends to take on jazz, which is more contemporary within his context. Margaret Bonds sort of experiments with that. But what is noticeable is that composers like her or Nora Holt go much further back and draw upon spirituals.”

“The reality is that composers such as Florence Price had relative privilege, and were somewhat disconnected from the history of that music,” she continued. “So that’s a really strong expression of one’s self – especially because there was some debate about what exactly is American folk music. Should it be Irish or Scottish melodies? What is our folk music?”

Though 85 years have passed since Price’s Symphony in E Minor premiered, Ege stresses that there is still work to be done to make classical music more inclusive. One way, she suggests, we can all work together to be more supportive of diverse voices in music is to take advice that Florence Price offered Serge Koussevitzky in a letter: “Disregard my race and gender for a moment and just listen to the music.”

“Race and gender, for Black women, are intertwined. I don’t advocate color blindness because that’s part of who we are,” Ege said. “But I do advocate for really thinking about the prejudices that you have and working to set them aside to try to appreciate music on its own.”