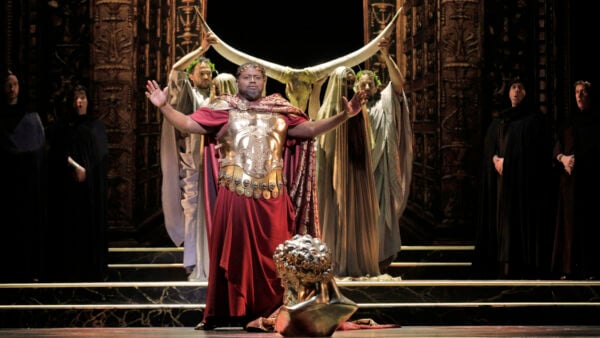

Eric Owens and Adina Aaron in Porgy and Bess (Photo: Todd Rosenberg)

"Summertime" from George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess is doubtless one of the one most popular songs in the Great American Songbook. But did you know that neither the tune to "Summertime" nor the lyrics are by George Gershwin?

First, let's start with the lyrics.

Porgy and Bess is based upon the novel Porgy by DuBose Heyward. Published in 1925, the novel was first adapted for the stage in 1927 by the author's wife, Dorothy Heyward. The play, in turn, inspired George Gershwin's Porgy, which he called "an American folk opera."

DuBose Heyward collaborated with Ira Gershwin to craft the libretto for Porgy and Bess, even spending time together in Charleston, South Carolina, to research African American communities and their music.

The lyrics to "Summertime" are by Heyward. Stephen Sondheim, the acclaimed composer and lyricist, wrote in his book Invisible Giants: Fifty Americans Who Shaped the Nation But Missed the History Books:

"DuBose Heyward has gone largely unrecognized as the author of the finest set of lyrics in the history of the American musical theater – namely, those of Porgy and Bess. There are two reasons for this, and they are connected. First, he was primarily a poet and novelist, and his only song lyrics were those that he wrote for Porgy. Second, some of them were written in collaboration with Ira Gershwin, a full-time lyricist, whose reputation in the musical theater was firmly established before the opera was written. But most of the lyrics in Porgy – and all of the distinguished ones – are by Heyward. I admire his theater songs for their deeply felt poetic style and their insight into character. It's a pity he didn't write any others. His work is sung, but he is unsung."

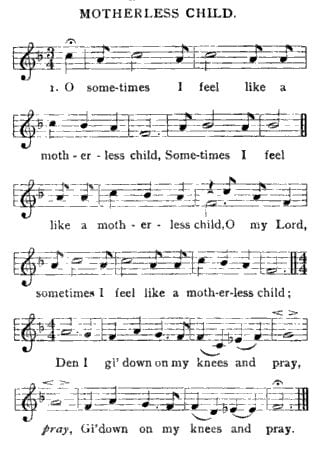

"Motherless Child," first print edition (1899)

Who gets credit for the music of "Summertime"? That question is a little more complicated. The melody is strikingly similar to an African American spiritual, "Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child."

Many commonly known spirituals today have come down to us from a collection of songs gathered by a white scholar during his visits to African American communities near Charleston, South Carolina, and published under the title Slave Songs of the United States in 1867.

While "Motherless Child" was not part of Slave Songs, a printed score of the song was available in print as early as 1899. When Gershwin and Heyward spent time in South Carolina to create Porgy, or perhaps even before, they could've encountered "Motherless Child."

The melody of the first printed version of "Motherless Child" only bears superficial similarities to "Summertime." The most significant difference is the key. "Summertime" sounds dark and doleful, in part, because it's in a minor key. This printed version of "Motherless Child" is in a major mode (with a few blue notes thrown in at the end).

Of course, spirituals exist in countless versions. By the time that Gershwin and Heyward were doing their research for Porgy in South Carolina, "Motherless Child" had changed into something decidedly different.

Paul Robeson, the great singer, actor, and civil rights activist, recorded the song in the 1930s. In his version, we could easily replace the words to "Motherless Child" with those to "Summertime" to hear how the original tune was subtly changed.

After the premiere of Porgy, it didn't take too long for folks to catch on to the similarities between "Summertime," which quickly became a standard, and "Motherless Child." The incomparable Mahalia Jackson caught on to the connection and even recorded the two songs together as a medley:

So, were the Gershwins and Heyward, a group of white men, stealing traditional African American music for their own profit?

Yes and no.

The history of Porgy and Bess is a complicated one. On the one hand, the opera is a celebration of African American culture. On the other hand, the primary agents who created it were white, and the Gershwin estate is what profits from "Summertime," not the community that created "Motherless Child." What's more, the representation of African Americans in Porgy has been praised and criticized by people of all colors as being nothing more than a collection of stereotypes.

A thoughtful new interpretation of Porgy by Gwynne Kuhner Brown sheds new light on the creation of Porgyand how we can understand these complicated issues. In her article "Porgy and Bess as Collaboration," printed in Blackness in Opera (2012), she writes:

"The history of Porgy and Bess is not simply one of white victimizers and black victims. African Americans have actively engaged with the work from the beginning: helping to create and shape it in a variety of ways, taking roles or refusing them, and deepening American society's understanding of its various meanings through analysis, criticism, and commentary. Most fundamentally, Porgy and Bess relies on African American performs to accept, inhabit, and essentially complete the work. This completion was begun in direct collaboration with George Gershwin, and continues today."

Since "Summertime" was first heard in 1935, it has become one of the most recorded songs in history. The Summertime Connection, an online database that compiles information about various versions of the tune, states that as of 2011, there have been at lest 33,345 recordings of "Summertime," 25,998 of which the website has in its own collection.

A handful of recordings reveal the variety of interpretations that abound of this classic American tune.

Leontyne Price recorded what may be the ultimate operatic version of this song, as shown in this performance at the White House in 1978. Price played the role of Bess during the 1952 revival tour by Belvins Davis and Robert Breen. The production visited several cities including Chicago, Pittsburgh, Washington, and even went on to Europe before returning to the US for a long run in New York.

Nina Simone was known for several songs from Porgy and Bess. She recorded a haunting "I Loves You Porgy" just days after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in a concert she dedicated to him. Her version of "Summertime" recorded live in 1959 at The Town Hall in New York is no less chilling.

Billy Stewart recorded one of the most commercially successful versions of "Summertime," which reached number 10 on the Billboard 100 in 1966. Stewart recorded for Chicago's Chess Records playing backup for many R&B legends including Bo Diddley. This arrangement features a brass band, funky guitar, and Stewart's signature scatting.

The Walker Brothers created a "wall of sound" in their cover of "Summertime," which was featured on their second album Portrait in 1966. The track is distinctive because of Scott Walker's soulful baritone and the rich vocal harmonies that support him.