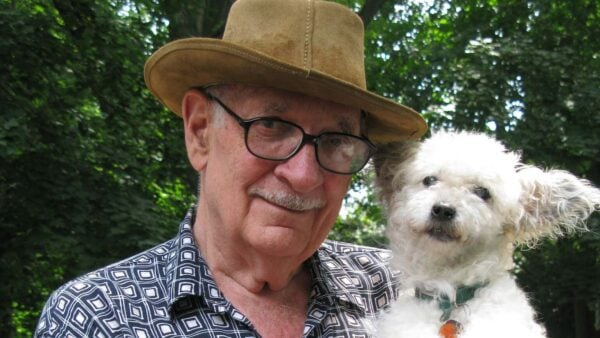

Composer Stacy Garrop

On the 50th anniversary of the very first Earth Day, WFMT presents a broadcast of Terra Nostra, an eco-oratorio by Chicago composer Stacy Garrop. The large-scale work, which Garrop shares took some inspiration from Mendelssohn’s Elijah, celebrates our planet and explores the relationship between humankind and the natural world. Using poetry by Shelley, Tennyson, Walt Whitman, and Edna St. Vincent Millay, as well as by contemporary poets Esther Iverem and Wendell Berry, the work progresses through three sections: “Creation of the World,” “The Rise of Humanity,” and “Searching for Balance.”

In anticipation of this broadcast and of Earth Day, WFMT spoke with Garrop about the genesis of the work, its poetic texts, and the importance of honoring and taking care of the planet.

WFMT: How did you come up with the idea to create this piece?

The idea of Terra Nostra came out of a workshop that I did with Volti many, many years ago. We were at a high school retreat in the Redlands of California, I was their guest composer for the weekend. And Volti artistic director Robert Geary asked, “If you would write an oratorio, what would it be about?”

Over the course of the next two days, I was just thinking, “here are all these students out in the middle of this beautiful wilderness.” By Sunday, a couple of days later, I said I wanted to write an oratorio about the planet. I submitted a proposal to the board of the San Francisco Choral Society, and I got an email a couple of months after that said that they’d approved the oratorio and were going to move forward with it.

From the get-go, Terra Nostra had been laid out as a three-part piece with the idea that the Choral Society of San Francisco was going to premiere in stages. We started with the premiere of Part I back in November of 2014. And then the next April, we premiered Part II. And then the following November, we premiered the entire thing together, so that for the first time, we heard Parts I, II, and III all assembled.

WFMT: How did you decide what poetry to use?

That was what probably took the most time. So from the point that the board approved for me to write the oratorio, I had already suggested some poets that I might be interested in working with their texts on. I started a massive list of different poems that I liked and poets who were interested in the environment.

It became a long haul of trying to figure out the story that I wanted to tell. And that story actually remained consistent from the very first proposal all the way to the final draft, but what changed was the flow: how was I going to tell this story?

Somebody like Walt Whitman was very easy to decide on because he has so much about the planet and he’s also out of copyright, so that made it a lot easier. One of the stipulations of the Choral Society is that they wanted to have a couple of poems by living poets, and that became the source of contention. Not that I disagree with them, because I completely agreed that this was important. The problem was getting permission from the living poets to be part of the oratorio.

I can’t remember who suggested Wendell Berry to me, it was one of my Chicago friends, but his poetry was spot on for what I needed to say. He had a poem called “The Want of Peace” that had just been written in 2012, so when I read that poem, I realized that that was actually a far better way of trying to say what I wanted to say. Luckily, and thankfully, the Counterpoint Press people who publish it were very gracious in giving me permission, and that settled it.

WFMT: When you see a poem, you’re perusing all this material, does something suddenly click and you say to yourself “Wow, this is musical”?

That’s a good question, because if people go through some of the selections that I have made, they’ll see that I’ve taken them exactly word-for-word. Like Edna St Vincent Millay’s “God’s World.” It’s word-for-word. Percy Shelley’s “On Thine Own Child.” But when I encounter someone like Walt Whitman, who’s so verbose and longwinded, I had to do a little bit of editing.

A lot of Whitman’s messages were spot on. There’s a poem about a blade of grass, and once I read it, it had to be in the piece. It became the focus of the end of Part I and then became the focus of the end of Part III as well. Since this thing premiered in stages, over the course of about a year, I wanted to give the audience something to hang on to for that year. So then they would remember that there’s some hope at the end of this whole thing when they hear the second part.

I came across another set of lines in the same book, Leaves of Grass, and it talks about how “I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love.” I found a way to take the first poem and the second poem and just weave them together, and that creates the end of the entire piece. Some of the other texts could come and go, but those had to be there.

WFMT: Does the piece change as you’re actually involved in rehearsal, or does it stay pretty much as you conceived it in your head and in the score?

What really helped was having the San Francisco Choral Society premiering the piece in stages, because it can be a little risky when you commission a composer for the whole 70-minute oratorio when they’ve never done that before. I found it very useful that we premiered Part I by itself. I could learn from what was happening in that rehearsal process and performance, and I could adjust and fix things in Parts II and III and rewrite Part I as needed.

And then new problems would come up that I would have to solve! There is one movement in Part III called the “Earth Screaming” with a text by contemporary poet Esther Iverem that I just blew some of the notes. The tenor and the baritone were hard to understand, and there was nothing I could do about it in the premiere performance. But that made it very easy for me to figure out how to solve it for the next round of performances.

So now it’s pretty much settled, and I think that actually has run very close to course. Whenever I write a new piece of music, I feel like it takes about three performances for everything to settle into place. And this took four. But hey, it is 70 minutes! So I think that’s not too bad off my mark.

WFMT: Tell us about your hopes for what this would do to the folks listening to the piece. What impression did you want to leave people?

What I would love for audiences to really take away from this is the original idea and intent of this whole story is that we are the stewards of the planet. We came from the planet. We’re returning to the planet. And while we are here, we really need to take care of it.

And what I think is very interesting right now in this crazy moment in time, when we’re all stuck at home because of the Coronavirus, is just that we’re seeing examples of how the planet is rebounding in having human contact dissipate from the cities and everything like that. What does our world really sound like when humans were not really part of the exterior world?

WFMT: One last question, how are you planning to celebrate Earth Day this year?

For one thing, I’ll listen to the broadcast of the piece! I’ll probably take a very short, quiet walk around the neighborhood and try to pay attention to everything I’m hearing around me. And go online to offer some words of encouragement for people out there who are also feeling the same way that we want to help the earth. We know we’re stuck inside. But what are some things that we can do when we’re finally all back together again?

WFMT airs a Northwestern University Symphony performance of Stacy Garrop’s Terra Nostra on April 22 at 8:00 pm. This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

![After 28 Years, Chicago Symphony Chorus Director Duain Wolfe Gives a 'Joyous Farewell' Duain Wolfe_credit Todd Rosenberg[2]](https://www.wfmt.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Duain-Wolfe_credit-Todd-Rosenberg2-600x338.jpg)