Leah Dexter (Nelda) and Michael Mayes (Daddy) in Chicago Opera Theater’s presentation of Taking Up Serpents (Photo: Sean Su for Chicago Opera Theater)

It has not been a normal year for opera, but then again, Taking Up Serpents is not a normal opera. Set in the Deep South, the opera portrays a young woman reckoning with her upbringing and her Pentecostal preacher father. In the words of its composer Kamala Sankaram, it’s a story about “negotiating one’s faith in the modern world, particularly through the lens of women.” Chicago Opera Theater will give a digital presentation of Sankaram’s opera, which she created with librettist Jerre Dye, on February 27 at 7:30 pm.

Employing a truly distinctive musical palette: the piece combines chamber opera with honky-tonk, prayer band, and other American music forms. First commissioned by the Washington National Opera before an expanded co-commission with COT and On Site Opera, the piece is set apart not only by its idiosyncratic focus and sound… but also by the fact that it’s happening at all. Sankaram expresses her appreciation that, thanks to COT, the opera will still reach audiences, even in its digital form.

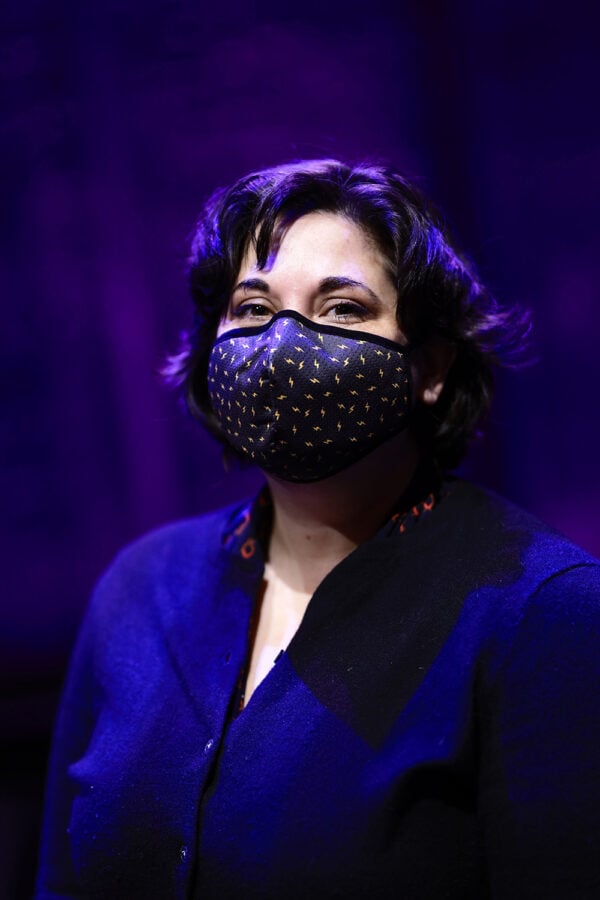

Composer Kamala Sankaram (Photo: Sean Su for Chicago Opera Theater)

Ahead of the digital premiere, WFMT spoke with Sankaram about her compositional inspirations, how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected her work and the opera industry as a whole, and how she thinks opera can grow and develop moving forward.

WFMT: What attracted you to the story?

Kamala Sankaram: Our commission from the Washington National Opera was to make a piece that had American themes. Jerre [Dye] and I were talking, and you don’t normally see the type of person we portray on stage at all, much less in an opera. There are some examples, like Carlisle Floyd’s opera, Susannah, which also takes place in Appalachia. But it seemed like an important thing to address. We decided to focus on this very small community, which is quotidian in a way that I think is sort of filled in by the size of opera. And then putting that on stage says this also is a story worthy of telling.

WFMT: COT has co-commissioned a longer 90-minute version of the piece. What was it like to expand the work from its original 60-minute form?

Sankaram: One of the things that we face in creating new opera that’s different from creating new theater is we don’t get previews, so you have your two or three performances in front of an audience, and that’s it. To be able to go back again is a luxury.

The original commission was very compact, but it felt like the arc of the story was there; it just needed a little more room to breathe. So, what we have done is to go back in and address a couple of specific questions that came up after that initial workshop. Otherwise, it’s been tightening things here, letting other spots breathe more there, and sort of fine-tuning.

WFMT: This pandemic has forced arts and opera organizations to rethink how they’re reaching their audience, in particular by embracing digital platforms. That’s not new to you; you’ve been on the bleeding edge of technology and art with your VR collaborations, interactive works, and even the Zoom opera that you unveiled during the pandemic. What do you see as the future for the art form, and how has the pandemic influenced or accelerated that path?

Sankaram: The way that people consume and are exposed to music is different now than it used to be. For most people, if they hear something for the first time, it’s going to come from the Internet. Part of the reason I have been so adamant about pushing into these new forms of distribution and technology is just simply getting people to hear.

I do think that hearing an opera singer in a theater is an experience that still can’t really be adequately captured in recording. Virtual reality and spatial audio come the closest, but 2D recording is not the same. But I think that that’s part of the reason why opera companies and classical music, in general, has been hesitant about recording is the dedication to the live sound, on top of contracts, which makes it prohibitively expensive to put recordings online and to even make them in the first place. What I hope everyone is realizing now is that you have the potential to reach so many more people if you have the recorded content that’s available in an accessible way.

[L-R] Composer Kamala Sankaram, librettist and stage director Jerre Dye, and conductor Lidiya Yankovskaya on the set of Taking Up Serpents (Photo: Sean Su for Chicago Opera Theater)

I really hope that this sort of hybrid sensibility, about capturing things in a better way and then allowing people who can’t get to a theater to see them, I hope that stays. Most people, especially in the United States, have never seen or heard an opera. And so, the idea of what opera is comes from things like TV commercials or depictions of or a villain who loves opera. Just allowing people more access is going to increase the number of people who say “I actually do like this! Maybe now I’m going to go to a theater.”

WFMT: This work challenges these popular ideas of opera that you bring up, not only it whom it portrays but also in its sound, which combines chamber opera with more traditionally American inspirations.

Sankaram: I approach writing for opera and theater by thinking about how music can be used to create character and place. It feels important in general — and it felt especially important in this piece — to link the music to the setting. There’s some praise band music, there’s honky-tonk, there’s shape-note singing, there are all of these things that are really specifically tied to the American South. Then that is placed within the context of more polytonal, post-tonal writing … to try and create the connection to mystery and to give the sense that there’s an added layer to everything that you’re hearing. That’s the best way that I could think of to musicalize what faith might sound like.

Soprano Alexandra Loutsion (Kayla) and baritone Michael Mayes (Daddy) (Photo: Sean Su for Chicago Opera Theater)

WFMT: Were there any particular reactions to your score?

Sankaram: My background is more in experimental music, where you’re allowed to throw whatever you want into a piece. But then working with Washington National Opera, I wasn’t really sure how they would feel about putting an electric guitar in the orchestra, but they were really game. Even things like having all the orchestra people play whirlytubes, we did it. I think that without having that collaborative partner early on, it might not have ended up the way that it is now. And even about the shape-note singing. That’s not something that opera singers are often asked to do. But universally, everyone has been really game to jump in and try it, even though it’s totally contrary to their training.

WFMT: What are you hoping viewers will take from this performance?

Sankaram: I would hope that they could think about what faith means to them. This is coming from somebody who is not at all religious. Throughout this whole piece, that’s been one of the things that has been important for me to think about; what does it mean to have this sense that there is something greater than what we can see or hear in front of us? It’s easy … to forget about that part and not engage with it, but I think an important part of being human is opening yourself to that spiritual dimension. Even if you walk away from it thinking, “Okay, I’ve opened myself and I still don’t get it. I still don’t agree.” Great! But at least you thought about it.

Chicago Opera Theater presents Taking Up Serpents by composer Kamala Sankaram and librettist Jerre Dye, premiering digitally Saturday, February 27 at 7:30 pm. The performance is conducted by COT music director Lidiya Yankovskaya, directed by its librettist Jerre Dye, and stars Alexandra Loutsion, Leah Dexter, and Michael Mayes. Digital tickets are available for $20 at cot.org. This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.