Utah Opera’s production of Moby-Dick (Photo: Dana Sohm / Utah Opera)

Moby-Dick is a Great American Novel, no doubt. But that fact doesn’t make Herman Melville’s 600+ page opus any less intimidating. For readers who got stuck somewhere in the middle of the colossal work (we can’t blame you if you were discouraged by the lengthy section of whale taxonomies), you can still join Ahab, the Pequod, and of course, the white whale, in opera form. Ahead of the opening of Chicago Opera Theater‘s production of Moby-Dick on April 25, we spoke with award-winning composer Jake Heggie about conquering an opera based on one of the American canon’s toughest and most rewarding reads.

WFMT: Where did the idea of adapting Moby-Dick into an opera come from?

Jake Heggie: Librettist Terrence McNally and I worked together on an opera called Dead Man Walking, which was very successful. We had been looking for another big project to do together. In 2005, the then head of the Dallas Opera approached me. He told me they were going to be building a new opera house and that for their inaugural season, they wanted to have a big and bold world premiere.

Composer Jake Heggie (Photo: Ellen Appel)

“This might be our opportunity to do something big,” I told Terrence. He replied, “There’s only one thing I want to do and that’s Moby-Dick.”

I was a little aghast … “Moby-Dick? Okay. That is big and bold.” But then I saw this twinkle in his eye, and I was reassured. Once we convinced the people at the Dallas Opera that it was a good idea, we were going full steam ahead. Terrence had to withdraw from the project after about a year because of health reasons, but then Gene Scheer took over the libretto.

Terrence gave me some guiding ideas before he had to withdraw. One was that Ahab should be a heldentenor. A lot of people think that Ahab is evil, so he should be a bass. Actually, the character isn’t evil. He’s an obsessed and troubled man. The heldentenor idea made sense to me because Ahab has the most heroic beautiful language in the book. He’s a deeply poetic soul, and he has to have the kind of personality and voice that could persuade everyone to follow him with glee.

WFMT: Reading Moby-Dick alone is a notorious undertaking, much less composing an opera based on it. How did you feel about adapting it?

Heggie: I like to take on projects that terrify me. I’ll know I can do them, but won’t know how the hell I’m going pull them off.

WFMT: What were some of your first impressions of the Melville novel?

Heggie: The book has really clear characters with very clear desires for what they want in the world. And then there is one lost soul — the guy who calls himself Ishmael. In the book, he’s a narrator, but I didn’t want a narrator on stage for the opera — I wanted to see things happen in real time. But you can’t put a book on the stage. That does not work. I knew if we were going to do Moby-Dick as an opera, we were going to have to change things around and rethink it.

I don’t remember exactly when it happened, but it struck me instead of being the first line of the opera, like the book, “Call me Ishmael” should be the last line. In other words, we’re watching the journey of that lost soul, whom we named Greenhorn, looking for his place in the world. What is it that leads him to that point so that he will then go on to be the one to write the book? That way, we could tell the story actively rather than from a narrator standpoint. And we could also invent things, because of course, if Greenhorn is going to go on and write the book, he’s going to change things when he writes. That gave us the liberty to change things for the stage piece: conflate characters, move events around, change what he sees. Gene ended up only using about 50 percent Melville in his libretto. The other 50 percent is Gene’s language, but it’s very much in the spirit of Melville.

WFMT: What was it like to create a score from the Melville text?

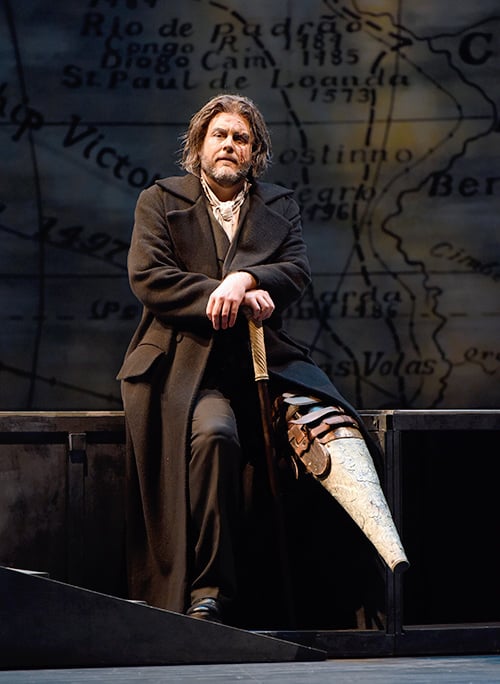

Richard Cox as Ahab in Opera San José’s production of Moby-Dick (Photo: Pat Kirk / Opera San José)

Heggie: When I read the book, I realized it was overflowing with music. The writing is lyrical, it’s big, it’s bold, it’s emotional. It’s about intimate journeys in a vast landscape, which I think are the best stories for opera. Intimate stories with large forces at work beyond anyone’s control. And it’s also people wrestling with their identity and their place in the world. All these big universal meditations are extraordinarily operatic.

Ahab was the most elusive as I was writing. I had about 60 pages of music, but none of it was right, because I still didn’t know who Ahab was. He was still kind of a caricature to me until I found his monologue of his halfway through Act One — “I leave a white and turbid wake.” It’s when you can see a real human being standing there. Ahab realizes that he’s losing his mind, that he’s losing touch, and is confused by why he can’t get it back. That’s very real, and very human, and very deep. I wrote that aria, and suddenly, Ahab was speaking loudly to me. I went to the beginning of the opera again and wrote the whole thing in about four months.

WFMT: This production reimagines the “big and bold” Dallas Opera production into something a little more intimate. What is unique about this new production, and why was it necessary?

Heggie: We had to rethink and come up with a fresh perspective, because medium and smaller companies could not just repeat what we had done with the larger-scale opening production. This more intimate imagining aims to tell the story clearly and efficiently, with elements of surprise and magic, but without projections, or computer graphics, or things flying around. They did that through this brilliantly conceived unit set created by this unbelievable designer named Erhard Rom. They also used a group of professional dancers to capture some of the poetry. This production comes off as more Shakespearean to me. In this imagining, the characters are the scenery much more so than the massive set like we had in the beginning. I think it’s a brilliant reimagining.

WFMT: How does it feel to have this opera debut in Chicago, with Chicago Opera Theater?

Heggie: Oh how exciting. I love Chicago! To have Moby-Dick arrive in Chicago with this fabulous production is thrilling. COT has assembled a really great cast, and I am such a fan of music director Lidiya Yankovskaya — I think she’s fantastic.

In addition to being incredibly challenging musically, the piece is very challenging staging wise. As Ahab, Richard Cox has to have his leg strapped into a peg leg all night. He moves all over that stage in it, and all the while, he has to sing this incredibly demanding music. It’s kind of crazy but everyone’s so game. It’s very exciting.

Chicago Opera Theater is a relatively young company, but they have a choice of doing any kind of repertoire they want. And they choose to do something more contemporary! This programming has opened so many doors for young composers and young artists who are interested in newer work. These companies are interested in exploring a range of different voices from different composers so different backgrounds, different styles of music, different stories, and that is really exciting.

I think it’s an amazing time for American opera. When Dead Man Walking premiered 20 years ago, it was one of maybe two or three American world premieres that year. Now, every year there are dozens. This is not really happening anywhere else in the world. It is really thrilling and it means that the art form is still alive and versatile, and we’re still discovering different things that they are can do.

Moby-Dick runs from April 25 to April 28 at the Harris Theater. For ticketing and information, visit chicagooperatheater.org.

Editor’s note: this interview has been lightly edited for clarity.